Introduction

Multilingualism, the ability to use and understand multiple languages, is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon with profound implications for cognitive development and communication. This ability extends beyond mere linguistic capability; it influences cognitive processes, educational outcomes, and social interactions. Multilingual individuals often navigate diverse linguistic landscapes, which can shape their cognitive abilities and affect their learning and problem-solving skills in unique ways.

The study of multilingualism encompasses various dimensions, including bilingualism, the cognitive impact of learning multiple languages, and the nuances of different types of bilingualism. Bilingualism, a subset of multilingualism, involves proficiency in two languages, while multilingualism refers to the ability to use more than two languages. These abilities are not just practical skills but are deeply intertwined with cognitive development, affecting how individuals think, process information, and solve problems.

Research into multilingualism has revealed that it can enhance certain cognitive functions, such as executive control, attention, and memory. For instance, bilingual individuals often exhibit superior executive functions compared to their monolingual counterparts. These functions include the ability to switch tasks efficiently, maintain focus amidst distractions, and manage competing cognitive demands. Such cognitive advantages are attributed to the constant mental juggling required to switch between languages and manage two or more linguistic systems.

However, the impact of multilingualism is not universally positive. The cognitive benefits associated with bilingualism can be influenced by various factors, including the age of acquisition, the frequency of language use, and the socio-cultural context in which the languages are learned. For example, bilingual individuals may face challenges such as slower lexical access in each language compared to monolinguals. This occurs because bilinguals need to manage and retrieve vocabulary from multiple languages, which can sometimes slow down their retrieval process.

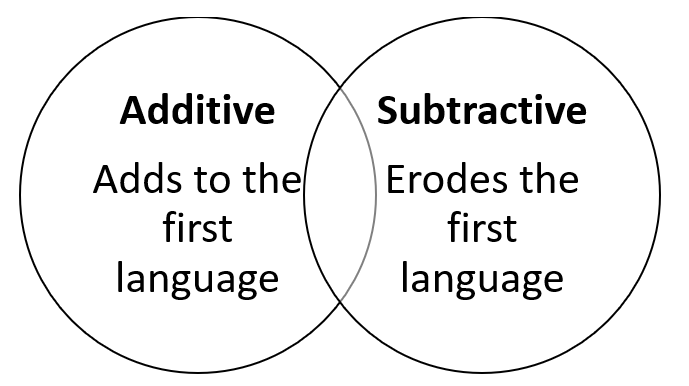

Understanding multilingualism also involves examining the different types of bilingualism. Bilingualism can be additive or subtractive, simultaneous or sequential. Additive bilingualism refers to the acquisition of a second language in addition to the first, without replacing or diminishing the first language. This type of bilingualism is generally associated with positive cognitive and academic outcomes. Conversely, subtractive bilingualism occurs when the acquisition of a second language leads to the erosion or replacement of the first language, often resulting in reduced cognitive and academic performance.

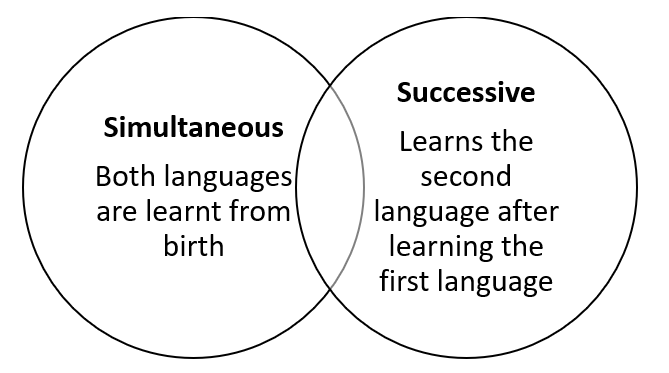

Simultaneous bilingualism occurs when an individual learns two languages from birth or early childhood, leading to balanced bilingualism where both languages are used with similar proficiency. Sequential bilingualism, on the other hand, involves learning a second language after acquiring the first, which can lead to varying levels of proficiency depending on factors such as age of acquisition and exposure.

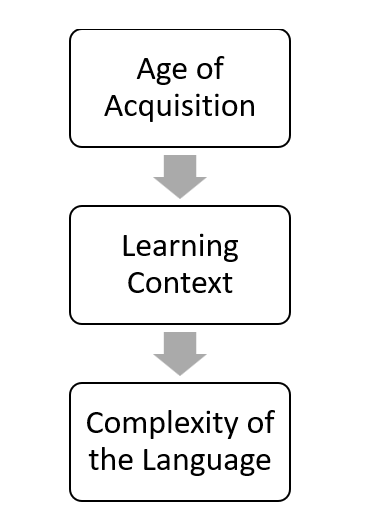

The cognitive and developmental effects of multilingualism are influenced by the context and experiences of language learning. Factors such as the age of acquisition, the similarity between languages, and the quality of language exposure play crucial roles in shaping language proficiency and cognitive outcomes. Research indicates that early exposure to multiple languages tends to lead to more favorable cognitive and developmental outcomes compared to later acquisition.

In addition to cognitive and developmental aspects, multilingualism also has implications for brain structure and function. Neuroimaging studies have shown that multilingual individuals often exhibit different patterns of brain activation and structural changes compared to monolinguals. For example, bilingualism has been associated with increased gray matter density in brain regions involved in language processing and executive control. These findings suggest that multilingualism can lead to changes in brain structure and function, reflecting the cognitive demands and benefits associated with managing multiple languages.

Overall, the study of multilingualism provides valuable insights into how language influences cognition, development, and brain function. It highlights the complex interplay between linguistic abilities and cognitive processes, underscoring the need for a nuanced understanding of how multilingualism shapes individual experiences and outcomes. Through detailed examination of bilingualism and multilingualism, researchers and educators can better appreciate the cognitive, developmental, and neurological dimensions of language use and acquisition.

Cognitive Implications of Bilingualism

Bilingualism and Cognitive Processes

Bilingualism can affect cognitive processes in several ways. A common question is whether bilinguals think differently in each language and whether bilingualism impacts cognitive functions compared to monolinguals. Research suggests that bilinguals might exhibit different cognitive patterns due to their ability to switch between languages and contexts.

Studies have indicated that bilinguals often engage in enhanced executive functions. Executive functions, which are primarily mediated by the prefrontal cortex, include cognitive abilities such as task switching, working memory, and inhibitory control (Bialystok, 2009). Bilingual individuals frequently switch between languages, which may improve their ability to switch tasks and control attention. For instance, Bialystok et al. (2004) found that bilinguals perform better on tasks requiring cognitive control compared to monolinguals.

Conversely, bilingualism might also introduce certain cognitive challenges. Research has shown that bilinguals can have smaller vocabularies in each language compared to monolinguals (Bialystok & Craik, 2010). This is partly because bilingual individuals must distribute their cognitive resources between two or more languages, potentially affecting their lexical access speed and overall vocabulary size. However, the impact of bilingualism on vocabulary is complex and can vary based on factors such as language dominance and frequency of use.

Bilingualism and Intelligence

The relationship between bilingualism and intelligence has been debated. Some studies suggest that bilingualism can enhance certain cognitive abilities, such as problem-solving skills and creativity (Peal & Lambert, 1962). This is supported by the notion that bilingualism involves frequent cognitive switching and control, which might foster intellectual flexibility.

On the other hand, other studies have found no significant differences in overall intelligence between bilingual and monolingual individuals (Hakuta et al., 2003). The potential cognitive benefits of bilingualism may be specific to certain cognitive domains rather than general intelligence. For instance, bilingual individuals often show enhanced abilities in tasks that require selective attention and cognitive control but do not necessarily demonstrate higher overall IQ scores.

Types of Bilingualism

Additive vs. Subtractive Bilingualism

Cummins (1976) distinguished between additive and subtractive bilingualism. Additive bilingualism occurs when the acquisition of a second language complements and adds to an individual’s existing linguistic abilities without replacing their first language. In contrast, subtractive bilingualism involves the replacement or erosion of the first language due to the acquisition of a second language.

Additive vs. Subtractive Bilingualism

Additive bilingualism is generally associated with positive cognitive and educational outcomes. For example, individuals who learn a second language in addition to a well-developed first language often experience enhanced cognitive flexibility and problem-solving skills (Cummins, 1981). On the other hand, subtractive bilingualism can lead to reduced cognitive development and academic performance, particularly if the acquisition of the second language is associated with the loss of the first language (Cummins, 1976).

Simultaneous vs. Sequential Bilingualism

Bilingualism can also be categorized based on the timing of language acquisition: simultaneous and sequential bilingualism. Simultaneous bilingualism occurs when a child learns two languages from birth, while sequential bilingualism happens when an individual learns a second language after acquiring their first language (Bhatia & Ritchie, 1999).

Simultaneous vs. Sequential Bilingualism

Simultaneous bilinguals often develop a high degree of proficiency in both languages if exposed to them in rich and meaningful contexts (Pearson et al., 1997). They typically exhibit balanced bilingualism, where both languages are used with similar frequency and proficiency. Sequential bilinguals, however, may experience varying levels of proficiency depending on factors such as age of acquisition, exposure, and context.

Factors Influencing Second-Language Acquisition

- Age of Acquisition

The age of acquisition plays a crucial role in second-language acquisition. Early language learners often achieve higher levels of fluency and native-like pronunciation compared to those who begin learning a second language later in life (Birdsong, 2009). However, recent research suggests that certain aspects of second-language acquisition, such as vocabulary and syntactic comprehension, can be successfully learned later in life (Bahrick et al., 1994; Herschensohn, 2007).

A critical period hypothesis posits that there is an optimal window for acquiring a language with native-like proficiency, usually ending around puberty. However, this hypothesis has been challenged by studies showing that late learners can still achieve high levels of proficiency, particularly if they engage in immersive language environments (Flege, 1991).

- Learning Context and Experiences

The context and nature of language learning experiences significantly impact second-language acquisition. Factors such as the method of instruction, exposure to the language, and the learner’s individual cognitive abilities all play a role in proficiency outcomes (Bialystok & Hakuta, 1994).

For instance, immersive language learning environments, where learners are frequently exposed to and use the target language, tend to yield better results compared to traditional classroom settings with limited exposure. Additionally, learners who engage in meaningful communication and practical use of the language often achieve higher proficiency (Krashen, 1982).

- Language Similarity and Complexity

The similarity between a learner’s first and second languages can influence the ease of acquisition. Languages that share common roots, such as English and Spanish, often have more similarities in vocabulary and grammar, making them easier to learn (Maratsos, 1998). Conversely, languages with significant differences, such as English and Russian, present more challenges due to differences in phonology, syntax, and grammar.

Factors Affecting SLA

Neuroscience of Multilingualism

Brain Structure and Function

Neuroscientific research has explored how multilingualism affects brain structure and function. Learning a second language increases the gray matter density in the left inferior parietal cortex, which is associated with language processing (Mechelli et al., 2004). This area of the brain becomes denser with greater proficiency in a second language, suggesting that bilingualism has a positive impact on brain structure.

Research also indicates that the age of acquisition influences brain structure. Earlier acquisition of a second language is associated with higher gray matter density, while later acquisition tends to show less density (Petitto et al., 2012). This suggests that early language learning has a more profound impact on brain development.

Brain Damage and Language Recovery

Studies involving bilingual individuals with brain damage have provided insights into how languages are represented in the brain. Research has shown mixed results regarding whether languages are represented in separate brain regions or in overlapping areas. Some studies suggest that different brain areas are activated for each language, while others indicate that there is significant overlap (Garcia et al., 2010; Gandour et al., 2007).

For example, a study by Meinzer et al. (2007) found that a bilingual individual who suffered a stroke and received training in one language showed significant recovery in that language but not in the other. This supports the idea that different languages might be represented in distinct brain regions.

Activation Patterns

Recent research using techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has explored activation patterns in the brain during language use. Studies have found that early bilinguals show overlapping activation in the left inferior frontal gyrus for both languages, whereas late bilinguals exhibit separate activation patterns (Kim et al., 1997). This suggests that the timing of language acquisition can influence how languages are processed in the brain.

Language Mixtures and Dialects

Language contact between different linguistic groups can result in the creation of pidgins and creoles. Pidgins are simplified languages that develop as a means of communication between groups with different native languages. They typically have limited vocabulary and simplified grammar and do not have native speakers (Wang, 2009).

Creoles arise when pidgins evolve over time and develop into fully functional languages with their own grammar and vocabulary. An example is Haitian Creole, which combines elements of French and West African languages. Creoles often exhibit characteristics of both the contributing languages and new linguistic innovations (Bickerton, 1990).

Dialects

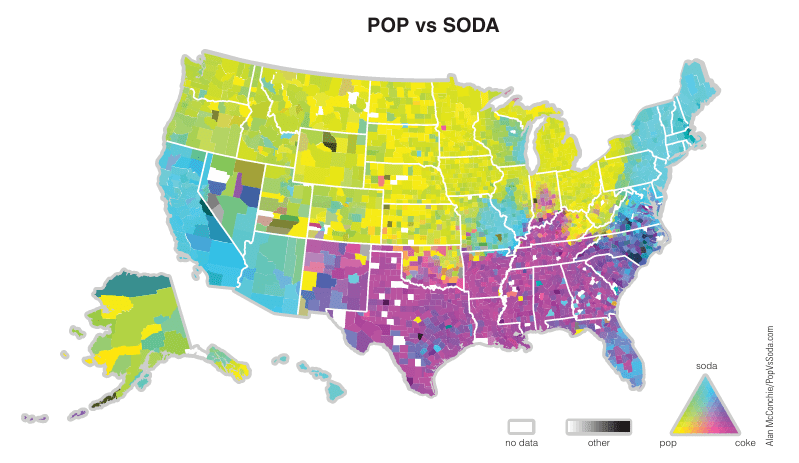

Dialects are regional or social variations of a language characterized by distinct vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammar. The study of dialects provides insights into how languages evolve and how social and geographical factors influence language use. For example, the term used for a soft drink can vary widely based on dialect, with different regions using terms such as “soda,” “pop,” or “Coke”.

Soda vs Pop

Conclusion

Multilingualism and second-language acquisition involve complex cognitive and neural processes. Bilingualism can offer cognitive advantages, such as enhanced executive functions and potentially delayed onset of dementia, but it may also present challenges like slower lexical access. The nature of bilingualism—whether additive or subtractive, simultaneous or sequential—affects its outcomes. Factors such as age of acquisition, learning context, and language similarity play crucial roles in second-language proficiency. Neuroscientific research has revealed that bilingualism impacts brain structure and function, although the exact nature of language representation remains an area of ongoing study. Additionally, the creation of pidgins and creoles and the variation within dialects illustrate the dynamic nature of language and its development.

References for Multilingualism

Bahrick, H. P., Hernandez, A. E., & Garcia, T. (1994). Long-term maintenance of second language vocabulary knowledge in an immersive environment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 15(4), 327-349.

Bialystok, E. (2009). Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 12(1), 3-11.

Bialystok, E., & Craik, F. I. M. (2010). Cognitive and linguistic control in the bilingual mind. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 20-23.

Bialystok, E., & Hakuta, K. (1994). In Other Words: The Science and Psychology of Second-Language Acquisition. Basic Books.

Bhatia, T. K., & Ritchie, W. C. (1999). The Handbook of Bilingualism. Blackwell Publishing.

Birdsong, D. (2009). Biological foundations of language. In The Handbook of Language and Cognitive Science (pp. 143-161). Wiley-Blackwell.

Bickerton, D. (1990). Language and Species. University of Chicago Press.

Cummins, J. (1976). The influence of bilingualism on cognitive growth: A synthesis of research findings and explanatory hypotheses. Working Papers on Bilingualism, 9, 1-43.

Cummins, J. (1981). The Role of Primary Language Development in Promoting Educational Success for Language Minority Students. California State Department of Education.

Flege, J. E. (1991). Age of learning and second language speech. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 89(1), 395-408.

Garcia, L. J., et al. (2010). Brain activation patterns during language processing in bilingual individuals: A meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(2), 289-308.

Gandour, J. T., et al. (2007). Neural correlates of language switching in bilinguals. Cognitive Neuroscience, 18(4), 153-163.

Herschensohn, J. (2007). Language Development and Age. Cambridge University Press.

Kim, K. H., et al. (1997). The effects of age of acquisition and language proficiency on the neural representation of bilingualism. NeuroImage, 6(4), 327-336.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Pergamon Press.

Maratsos, M. P. (1998). The Acquisition of the English Past Tense. MIT Press.

Meinzer, M., et al. (2007). Recovery of language abilities in bilinguals after stroke: A longitudinal study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 78(10), 1026-1033.

Mechelli, A., et al. (2004). Second language learning: Structural brain changes. Nature, 431(7010), 757-760.

Pearson, B. Z., et al. (1997). The role of language exposure in bilingual language development. International Journal of Bilingualism, 1(2), 121-141.

Petitto, L. A., et al. (2012). Bilingualism and the brain: The role of age of acquisition in the neural representation of bilingualism. Brain and Language, 120(1), 80-94.

Peal, E., & Lambert, W. E. (1962). The relation of bilingualism to intelligence. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 76(27), 1-23.

Sternberg, R. J., & Sternberg, K. (2006). Cognitive psychology (p. 178). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Wang, W. S.-Y. (2009). Pidgin and Creole Languages. Routledge.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 18,513 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, September 26). Multilingualism and Second-Language Acquisition- Learn About 3 Wonderful Factors That Influence this Insightful Phenomena. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/multilingualism/