Introduction

The connectionist perspective, as championed by Rumelhart and McClelland, provides a compelling framework for understanding memory processes, diverging from traditional serial processing models by embracing the brain’s parallel and distributed nature. Their work introduces a paradigm shift, suggesting that the human brain’s ability to process multiple operations simultaneously makes it a more complex and efficient system than previously captured by sequential models.

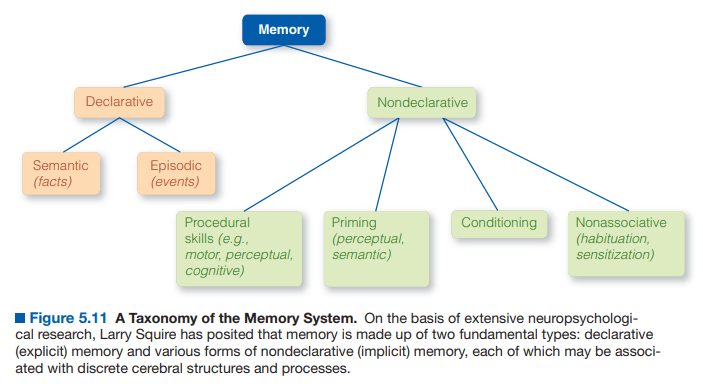

Types of Memory Systems

The Core of Connectionist Models

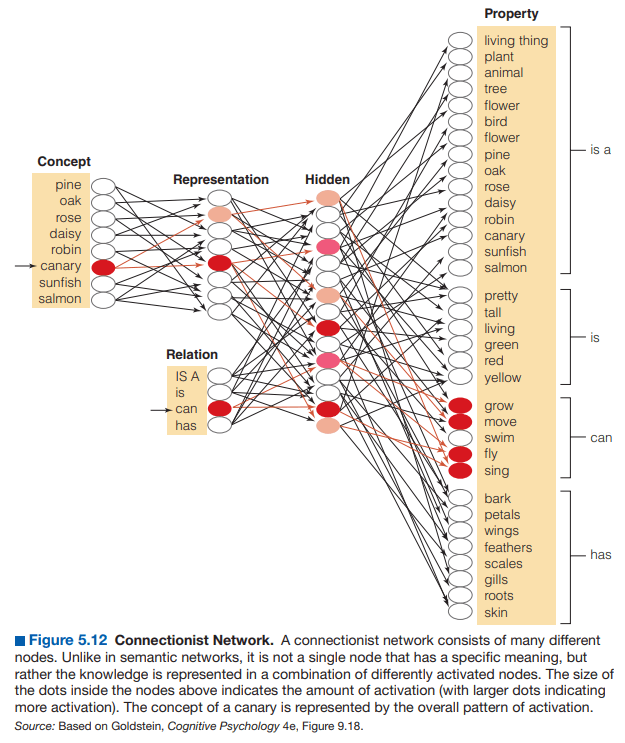

At the heart of the connectionist approach is the parallel distributed processing (PDP) model, which simulates the brain’s ability to process multiple streams of information at once. Unlike traditional models, such as the three-store model, which conceptualize memory as linear and sequential, the PDP model emphasizes the brain’s network of interconnected, neuron-like computational units called nodes. In this model:

- Knowledge is stored not in individual nodes but in the connections between nodes (Rumelhart, McClelland, & PDP Research Group, 1986).

- Activation spreads through the network when a node is stimulated, and this activation triggers connected nodes in parallel.

This concept of spreading activation underpins how the brain retrieves and processes information. For instance, recognizing a canary may activate not just its attributes (e.g., “yellow,” “sings”) but also its relation to broader categories (e.g., “bird,” “animal”). These simultaneous activations reflect the interconnected nature of memory storage and retrieval (McClelland & Rumelhart, 1985, 1988).

Spreading Activation in the Connectionist Perspective

Priming and Spreading Activation

One of the most well-supported phenomena explained by the connectionist model is priming, where activation of one concept facilitates the retrieval of related concepts. For example, seeing the word “flower” might make it easier to recall “rose” or “daisy.” This effect is attributed to the spreading activation within the network-

- A prime node activates its connected nodes, reducing the effort needed to retrieve related information.

- Experimental tasks, such as word-completion tasks, provide empirical support for this mechanism. These tasks show that recently activated concepts are more readily accessible, aligning with the connectionist framework (McClelland & Rumelhart, 1988).

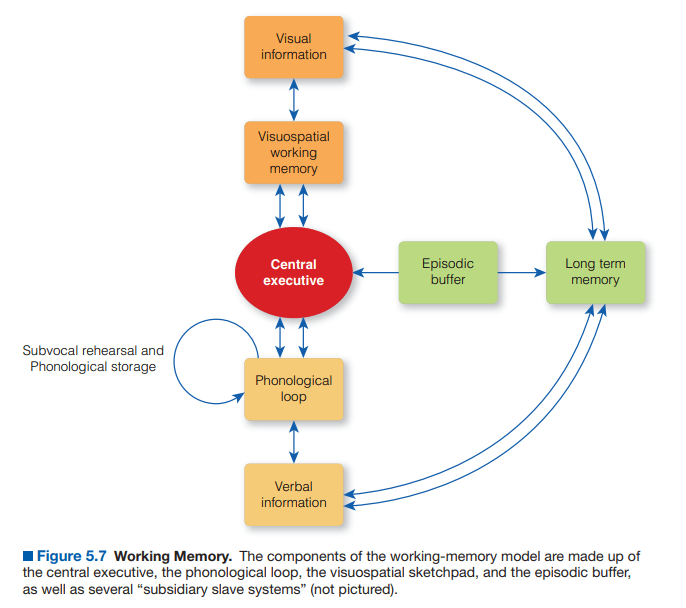

Working Memory and the PDP Model

The connectionist perspective also integrates seamlessly with modern notions of working memory. In this model-

- Working memory is viewed as the activated portion of long-term memory, with activation spreading through the network until it reaches the limits of the system (Frean, 2003).

- Parallel processing within the network allows for simultaneous handling of multiple operations, enhancing efficiency (Sun, 2003).

Working Memory

This perspective supports the view that humans excel in processing complex tasks precisely because of the brain’s ability to manage parallel operations, unlike traditional computers that rely on sequential processing.

Read More- Working Memory

Challenges to the Approach

Despite its intuitive appeal and empirical support, the connectionist model has faced criticism. Opponents, such as Fodor and Pylyshyn (1988), argue that-

- Human cognition exhibits a top-down orderliness and systematicity that connectionist models, with their bottom-up structure, struggle to explain.

- Complex behaviors often display purpose and integration that seem beyond the reach of current connectionist frameworks.

Proponents of the connectionist approach, however, argue that these critiques can be addressed through further refinement of the models. As cognitive psychologists continue to explore the boundaries of this paradigm, they aim to resolve these debates and expand the model’s explanatory power.

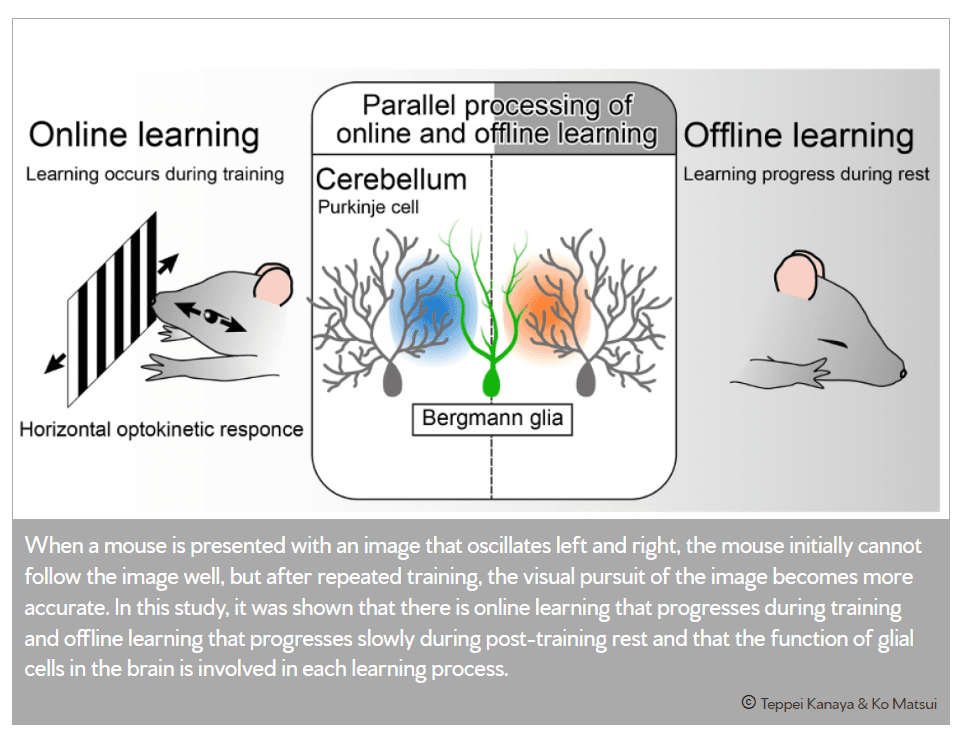

Evidence of Parallel Processing

Significance of the Connectionist Approach

The connectionist perspective has revolutionized memory research by-

- Inspiring a shift from serial to parallel processing models, better aligning with the brain’s actual operations.

- Providing a robust framework to explain phenomena like priming and implicit memory.

- Emphasizing the dynamic and interconnected nature of memory, which integrates well with neuropsychological findings.

Moreover, the connectionist model’s ability to simulate learning, memory retrieval, and skill acquisition has made it a valuable tool for experimental studies in cognitive psychology.

Future Directions

The existence of multiple memory models underscores the complexity of human cognition. While connectionist models have proven invaluable, ongoing research aims to refine and integrate these models with others to form a comprehensive theory of memory. As researchers like Rumelhart and McClelland have shown, exploring the brain’s parallel and distributed processes is key to unlocking the mysteries of human memory.

In summary, the connectionist perspective provides a powerful lens through which to view memory. Its emphasis on networks, parallel processing, and interconnectedness continues to shape our understanding of how we encode, store, and retrieve information.

References

Fodor, J. A., & Pylyshyn, Z. W. (1988). Connectionism and cognitive architecture: A critical analysis. Cognition, 28(1–2), 3–71.

Frean, M. (2003). The structure and dynamics of memory in connectionist systems. Journal of Theoretical and Experimental Artificial Intelligence, 15(1), 5–25.

McClelland, J. L., & Rumelhart, D. E. (1985). Distributed memory and the representation of general and specific information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 114(2), 159–197.

McClelland, J. L., & Rumelhart, D. E. (1988). Explorations in Parallel Distributed Processing: A Handbook of Models, Programs, and Exercises. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rumelhart, D. E., McClelland, J. L., & PDP Research Group. (1986). Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition. Volume 1: Foundations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sternberg, R. J., & Sternberg, K. (2016). Cognitive psychology (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Sun, R. (2003). Connectionist models of memory and learning. Philosophical Psychology, 16(1), 25–49.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 18,513 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, January 29). Connectionist Perspective to Memory and 2 Important Challanges to It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/connectionist-perspective/

Thank you