Introduction

Psychotherapies are one of the most significant methods through which psychological distress is addressed and human development is promoted. It is both an art and a science that combines theoretical understanding, empirical evidence, and interpersonal sensitivity to foster change, growth, and healing. Within counselling psychology, psychotherapy represents a systematic, intentional, and collaborative process between a therapist and a client aimed at alleviating distress and promoting well-being (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Read More: Projective Techniques

Definition of Psychotherapy

The term psychotherapy is derived from two Greek words: psyche (mind or soul) and therapeia (healing or treatment). In essence, psychotherapy means “healing of the mind.” Prochaska and Norcross (2007) define psychotherapy as the systematic application of clinical methods and interpersonal stances derived from established psychological principles for assisting people in modifying their behaviors, cognitions, emotions, and other personal characteristics toward desired change. Similarly, Corsini and Wedding (1995) describe psychotherapy as a formal process of interaction between two parties—the therapist and the client—within a professional relationship that seeks to bring about positive psychological change.

Counselling psychologists have traditionally emphasized the developmental and preventive functions of psychotherapy. Gelso and Fretz (1995) argue that psychotherapy within counselling psychology is not restricted to treating pathology but extends to facilitating optimal human functioning, personal growth, and self-understanding. Thus, psychotherapy encompasses both the remediation of difficulties and the enhancement of strengths.

The Nature of Psychotherapy

The nature of psychotherapy can be understood through several interrelated dimensions: its goals, assumptions, processes, theoretical orientations, and cultural foundations.

Goals of Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy aims to:

- Relieve psychological distress

- Promote behavioral change

- Enhance emotional regulation

- Foster personal development (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008).

According to Corey (2008), psychotherapy helps individuals gain insight into themselves and their relationships, develop problem-solving abilities, and enhance their sense of purpose and autonomy. Feltham and Horton (2006) note that psychotherapy operates on both remedial and growth-oriented goals: it treats mental and emotional difficulties while also promoting self-awareness and well-being.

Fundamental Assumptions

The practice of psychotherapy rests on several assumptions about human nature and change:

- Humans are capable of growth and self-regulation. Many therapeutic approaches—especially humanistic and cognitive–behavioral—assume that individuals possess an inherent tendency toward self-improvement when given appropriate conditions (Rogers, as cited in Feltham & Horton, 2006).

- Psychological distress is modifiable. Whether through insight, behavioral conditioning, or cognitive restructuring, psychotherapy assumes that maladaptive patterns can change (Beck, 1976; Rimm & Masters, 1987).

- The therapeutic relationship is central. Gelso and Williams (2022) affirm that the relationship between therapist and client is itself a primary vehicle for change, not merely a prerequisite for technique.

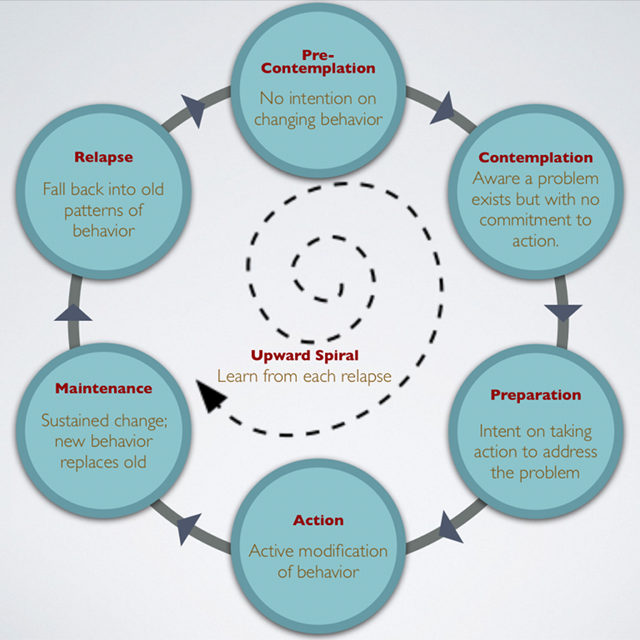

- Change is a process. As Prochaska and Norcross (2007) outline, change occurs through identifiable stages—precontemplation, contemplation, action, and maintenance—each requiring specific interventions.

Stages of Change

These assumptions make psychotherapy both a scientific and a humanistic enterprise—grounded in theory but centered on human experience.

Processes and Mechanisms of Change

Psychotherapy typically proceeds through several stages: assessment, formulation, intervention, evaluation, and termination. During these stages, therapists employ techniques consistent with their theoretical orientations while attending to the unique context of the client (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008). Despite variations in approach, research consistently identifies several common factors across psychotherapies: the therapeutic relationship, client motivation, therapist competence, and expectancy or hope (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Process of Psychotherapy

According to Beck (1976), cognitive therapy promotes change by identifying and modifying distorted beliefs and automatic thoughts. In contrast, behavioral therapy emphasizes conditioning and reinforcement to alter maladaptive behaviors (Rimm & Masters, 1987). Psychodynamic approaches, originating from Freud, emphasize insight into unconscious processes and past experiences that shape current functioning. Humanistic and existential models emphasize authenticity, choice, and meaning (Watts, 1973; Feltham & Horton, 2006). Despite these differences, all approaches aim to restore equilibrium and foster adaptive functioning.

Theoretical Orientations

Psychotherapy is characterized by theoretical pluralism. Prochaska and Norcross (2007) classify psychotherapies into major systems such as psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, humanistic, existential, systemic, and integrative approaches. Each system offers unique perspectives on human functioning and therapeutic change:

Goals of Different Therapies

- Psychodynamic Approach: Psychodynamic therapy emphasizes the influence of unconscious motives, conflicts, and early life experiences on present behavior (Corsini & Wedding, 1995). It explores how unresolved childhood experiences shape personality and current relationships. Central concepts include defense mechanisms (such as repression, projection, and denial) and transference, where clients project past feelings onto the therapist. The therapeutic process aims to bring unconscious material into awareness, promoting insight and emotional resolution. Ultimately, it helps clients gain self-understanding and integrate hidden aspects of the self (Gelso & Fretz, 1995).

- Behavioral Approach: Behavioral therapies are grounded in the principles of learning theory, focusing exclusively on observable and measurable behaviors (Rimm & Masters, 1987). They assume that maladaptive behaviors are learned through conditioning and can therefore be modified through new learning experiences. Techniques such as systematic desensitization, reinforcement, modeling, and behavior rehearsal are used to alter behavioral patterns. The therapist plays an active, directive role in identifying environmental triggers and implementing behavior change strategies. This approach emphasizes empirical validation and present-focused intervention rather than exploring unconscious processes (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008).

- Cognitive Approach: Cognitive therapies, developed primarily by Aaron Beck (1976) and Albert Ellis (Ellis & Harper, 1975), focus on the idea that thoughts influence emotions and behavior. Psychological distress arises from dysfunctional beliefs and cognitive distortions, such as overgeneralization or catastrophizing. The therapeutic process involves identifying, challenging, and restructuring these distorted cognitions through cognitive restructuring and rational analysis. Clients learn to develop balanced, rational, and reality-based thought patterns, resulting in improved mood and functioning. Cognitive therapy laid the foundation for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), one of the most widely practiced evidence-based modalities.

- Humanist Approach: Humanistic therapy emphasizes personal growth, self-actualization, and the client’s inherent potential for positive change (Rogers, as discussed in Feltham & Horton, 2006). Carl Rogers’s person-centered therapy identifies three core conditions essential for therapeutic change: empathy, genuineness, and unconditional positive regard. The therapist provides a non-judgmental and accepting environment that allows clients to explore their experiences openly. Humanistic therapy focuses on the here and now, encouraging clients to reconnect with their authentic selves and take responsibility for their choices. This approach values subjective experience, autonomy, and the capacity for self-healing (Woolfe & Dryden, 1996).

- Existential Approach: Existential psychotherapy focuses on fundamental issues of human existence—freedom, responsibility, isolation, death, and the search for meaning (Watts, 1973). It views psychological distress not as pathology but as a natural response to existential anxiety and the struggle for purpose. The therapist assists clients in confronting these realities honestly and finding authentic meaning in life through conscious choice and self-awareness. Clients are encouraged to embrace their freedom and responsibility for shaping their lives, rather than avoiding uncertainty. This approach highlights authenticity, meaning-making, and personal courage as pathways to psychological well-being (Rama, Ballentine, & Ajaya, 1976).

- Systematic and Family Therapy Approach: Systemic and family therapies view psychological issues as arising from dysfunctional patterns of interaction within families or larger relational systems (Corey, 2008). They emphasize communication styles, boundaries, hierarchies, and feedback loops that maintain maladaptive patterns. The therapist focuses on altering these relational dynamics rather than targeting an individual as “the problem.” Techniques derived from structural, strategic, and Bowenian family therapy help members establish healthier roles and connections. This approach recognizes that change in one part of the system affects the entire network, making relational change central to healing (Verma, 1990).

- Integrative and Transtheoretical Approach: Integrative and transtheoretical models synthesize concepts and techniques from multiple psychotherapeutic schools to create flexible, individualized interventions (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007). The transtheoretical model of change outlines five stages—precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance—guiding therapists to match interventions to the client’s readiness for change. Integration may occur through technical eclecticism, theoretical integration, or assimilative integration, depending on therapist preference and client needs. These models emphasize collaboration, cultural responsiveness, and scientific grounding. By blending diverse approaches, they promote personalized, evidence-based, and context-sensitive therapy (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

The richness of psychotherapy thus lies in its diversity and adaptability to different clients and contexts.

Cultural and Eastern Contributions

While much of psychotherapy developed in Western contexts, there is growing recognition of indigenous and Eastern perspectives. Rama, Ballentine, and Ajaya (1976) emphasized the integration of yogic and meditative practices with psychotherapy, suggesting that self-awareness and consciousness expansion are crucial to healing. Veereshwar (2002) discussed Indian systems of psychotherapy rooted in spiritual and philosophical traditions that focus on the balance of body, mind, and spirit. Ajaya (1989) and Watts (1973) further highlight the convergence of Eastern contemplative traditions with Western psychotherapeutic principles, proposing that healing involves both personal insight and transcendence.

These perspectives broaden the nature of psychotherapy beyond the clinical to include spiritual and existential dimensions, recognizing that mental health is shaped by culture, philosophy, and community.

Ethical and Professional Nature

Psychotherapy operates within strict ethical and professional boundaries. According to Woolfe and Dryden (1996), ethical practice includes confidentiality, informed consent, professional competence, and the maintenance of clear boundaries. Gelso and Williams (2022) emphasize the importance of therapist self-awareness, supervision, and reflective practice as safeguards against misuse of power and boundary violations. The therapist’s personal qualities—empathy, genuineness, and self-reflection—are as essential as theoretical knowledge and technique.

Outcome and Effectiveness

Research consistently indicates that psychotherapy is effective across a range of mental health conditions and personal concerns. Although specific techniques contribute to success, the quality of the therapeutic relationship remains one of the strongest predictors of outcome (Gelso & Williams, 2022). Corey (2008) notes that successful therapy depends on the match between client needs, therapist orientation, and the collaborative alliance. Feltham and Horton (2006) stress that outcome is also influenced by extra-therapeutic factors, such as social support and life events.

The Nature of Change in Psychotherapy

Change in psychotherapy is multifaceted, encompassing cognitive, affective, behavioral, and existential dimensions.

- Cognitive and behavioral models conceptualize change as learning, acquiring new ways of thinking and acting (Beck, 1976; Rimm & Masters, 1987).

- Humanistic models view change as growth, realizing one’s potential and authenticity.

- Psychodynamic theories see change as insight, bringing unconscious material to awareness.

- Eastern and integrative models view change as transformation, achieving inner balance and self-realization (Rama et al., 1976; Ajaya, 1989).

Prochaska and Norcross (2007) suggest that sustainable change requires progression through stages, with the therapist adapting interventions accordingly. Gelso and Williams (2022) argue that the therapist’s capacity to engage authentically, manage transference–countertransference, and maintain the therapeutic alliance determines how effectively clients can internalize change.

Conclusion

Psychotherapy is a deliberate, theory-based, and relational process that facilitates psychological change and personal development. Its definition emphasizes the systematic and intentional application of psychological principles, while its nature highlights diversity, collaboration, and human potential. Across all orientations—psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, humanistic, systemic, and integrative—the goal remains the same: to alleviate suffering and foster growth. As Gelso and Williams (2022) affirm, psychotherapy is at the core of counselling psychology and represents both scientific rigor and human compassion in practice.

References

Ajaya, S. (1989). Psychotherapy: East and West. Himalayan International Institute.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press.

Capuzzi, D., & Gross, D. R. (2008). Counseling and psychotherapy: Theories and interventions (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

Corey, G. (2008). Theory and practice of group counseling (7th ed.). Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Corsini, R. J., & Wedding, D. (Eds.). (1995). Current psychotherapies (5th ed.). F. E. Peacock.

Feltham, C., & Horton, I. (Eds.). (2006). The Sage handbook of counselling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Gelso, C. J., & Fretz, B. R. (1995). Counselling psychology. Prism Books Pvt. Ltd.

Gelso, C. J., & Williams, E. N. (2022). Counseling psychology. American Psychological Association.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2007). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (6th ed.). Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Rama, S., Ballentine, R., & Ajaya, S. (1976). Yoga and psychotherapy. Himalayan International Institute.

Rimm, D. C., & Masters, J. C. (1987). Behavior therapy: Techniques and empirical findings. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Veereshwar, P. (2002). Indian systems of psychotherapy. Kalpaz Publications.

Watts, A. W. (1973). Psychotherapy East and West. Penguin Books.

Woolfe, R., & Dryden, W. (Eds.). (1996). Handbook of counselling psychology. Sage Publications.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 31). Psychotherapies: 2 Important Definitions and 4 Fundamental Assumptions. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/psychotherapies/