Introduction

Sleep is a complex biological and psychological process regulated by both homeostatic and circadian systems, involving brain structures, neurotransmitters, and feedback loops that maintain internal stability and energy balance. It’s a fundamental need—essential not just for rest, but also for motivation, emotion regulation, learning, and survival.

Read More- Thirst Motivation

The Two-Process Model of Sleep Regulation

Sleep is governed by two interacting biological systems-

- Process S (Sleep Homeostasis): This mechanism builds sleep pressure the longer we are awake. The brain accumulates adenosine, a by-product of energy metabolism, which increases the urge to sleep.

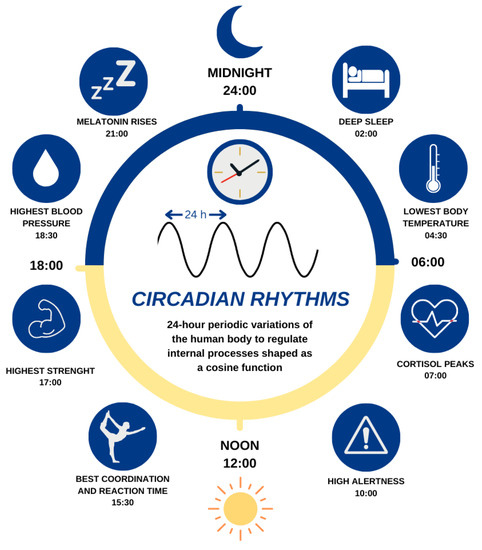

- Process C (Circadian Rhythm): Controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus, this 24-hour internal clock regulates sleep-wake cycles in response to light/dark cues.

Circadian Rhythms

Disruption in either process can cause insomnia or hypersomnia, as seen in breathing-related sleep disorders, where frequent awakenings prevent adequate sleep debt repayment or interfere with circadian timing.

Sleep Cycle

Sleep is not a uniform state but a cyclical progression through multiple stages, each with unique physiological and psychological functions. The two primary types of sleep are-

1. Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) Sleep

NREM sleep is divided into three stages-

- Stage N1 (Light Sleep): Transitional phase between wakefulness and sleep. Muscle activity slows, and eye movements stop. It lasts only a few minutes.

- Stage N2 (Intermediate Sleep): Heart rate slows, body temperature drops, and consciousness of the external environment fades. This is the longest sleep stage in a full night.

- Stage N3 (Slow-Wave Sleep / Deep Sleep): Characterized by delta waves. This stage is crucial for physical restoration, immune function, and the release of growth hormone. Disruptions in this stage impair energy levels, healing, and immune responses.

Stages of Sleep

2. Rapid Eye Movement (REM) Sleep

REM sleep is marked by:

- Intense brain activity

- Vivid dreams

- Muscle atonia (paralysis)

- High activity in emotional and memory-related regions (e.g., limbic system)

REM sleep plays a vital role in:

- Emotional processing

- Memory consolidation, especially for emotionally charged or procedural tasks

- Regulating mood and motivation

According to Ross Buck, REM sleep enables emotional integration—processing affective experiences and linking them to motivation and social behavior (Buck, 1976).

Neurobiological Mechanisms Involved in Sleep

Sleep involves a dynamic interaction of several brain regions-

Biology of Sleep & Wakefulness

- Brainstem and Pons: Control the transitions between sleep stages, especially REM sleep.

- Hypothalamus: Regulates circadian rhythms and produces orexin (hypocretin)—a neuropeptide that stabilizes wakefulness.

- Thalamus: Filters sensory signals during sleep.

- Basal Forebrain and preoptic area: Induce sleep by inhibiting arousal systems.

Key neurotransmitters involved include:

- GABA: Promotes sleep by inhibiting wakefulness centers.

- Adenosine: Accumulates during wakefulness and signals sleep need.

- Serotonin and Norepinephrine: Help regulate sleep stages, especially REM and NREM transitions.

- Dopamine: Influences wakefulness and motivation.

When sleep is fragmented by breathing interruptions—as in sleep apnea—these systems are constantly disrupted, leading to reduced time in restorative sleep stages, especially slow-wave sleep (SWS) and REM sleep, which are crucial for learning, memory, and emotional regulation.

The Sleep-Apnea Connection

In obstructive and central sleep apnea, the brain detects a drop in oxygen levels (hypoxemia) or a buildup of CO₂ (hypercapnia), triggering a sympathetic nervous system response. This results in a brief arousal to resume breathing, increasing heart rate and blood pressure. Though these awakenings are often not consciously remembered, they fragment sleep architecture and prevent progression into deeper sleep stages.

Buck (1976) emphasizes that sleep supports emotional integration and the ability to engage motivationally with the world. When the brain is chronically stressed by hypoxia or poor sleep, it disrupts the emotional motivational systems, which depend on the rhythmic, restorative nature of sleep to maintain baseline affect and motivation (Buck, 1976).

Sleep and Motivation

Ross Buck proposed that emotional and motivational systems are rhythmic and interdependent. Sleep supports:

- Recovery of neural circuits involved in reward and reinforcement

- Emotion regulation (by processing affective experiences during REM)

- Motivational reset (by recalibrating energy levels, attention, and self-regulation)

When sleep is interrupted—especially by breathing-related disorders—individuals often report:

- Decreased goal-directed behavior

- Blunted affective responses (less joy, less frustration tolerance)

- Lowered drive, interest, and curiosity

This aligns with findings that chronic sleep fragmentation lowers activation of the mesolimbic dopamine system, which is critical for motivation and the anticipation of reward.

Psychological Feedback Loops

Importantly, disrupted sleep can become a self-perpetuating cycle. Poor sleep reduces motivation, which leads to:

- Less physical activity

- Poorer lifestyle choices (e.g., diet, substance use)

- Reduced social engagement

These outcomes, in turn, worsen sleep—especially in obstructive sleep apnea where obesity, sedentary behavior, and low mood can all exacerbate symptoms.

Conclusion

Sleep is not a passive state; it is an active, complex, and essential biological function that regulates motivation, emotion, and cognition. In breathing-related sleep disorders, this finely tuned system is repeatedly disrupted, leading not only to physiological fatigue but also to motivational dysregulation, emotional blunting, and impaired functioning across social, occupational, and personal domains.

By understanding and treating the mechanisms of disrupted sleep, we can help restore the motivational systems that drive well-being and purposeful behavior.

References

Buck, R. (1976). Human motivation and emotion. New York, NY: Wiley

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 18,509 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2019, April 18). Motivation of Sleep and 2 Important Stages of Sleep. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/mechanism-of-sleep-or-sleep-motivation/