Introduction to Getzels and Jackson’s Theory of Creative Thinking

In their pioneering 1962 book Creativity and Intelligence, Jacob W. Getzels and Philip W. Jackson explored the relationship between creativity and intelligence, challenging the prevailing one-dimensional understanding of intelligence.

Their two-factor model of giftedness presented creativity and intelligence as interdependent yet distinct constructs, which interact to form unique problem-solving abilities in individuals. Through studies involving high-school students, Getzels and Jackson, along with contributions from Mel Rhodes, provided insights into how individuals approach complex problems creatively and how creativity is essential in innovative problem-solving.

Getzels and Jackson defined creativity as a process distinct from traditional intelligence, focusing on the ability to generate novel and original ideas, especially within the context of problem-solving.

Their approach emphasized creativity as the capacity to approach problems in unconventional ways, which involves the use of divergent thinking—generating multiple possible solutions to a problem. Creativity, according to Getzels and Jackson, emerges particularly in complex or ambiguous problem situations where conventional solutions are insufficient, requiring individuals to think flexibly and explore alternative approaches to arrive at innovative solutions (Getzels & Jackson, 1962).

Read More- Creativity

Problem-Solving as a Way to Creativity

Central to Getzels and Jackson’s approach is the idea that creativity emerges primarily in problem-solving situations. They argued that creative thinking is not a separate, isolated skill but a cognitive process that occurs naturally when individuals face challenges. Creative problem-solving becomes essential when conventional methods fail, necessitating novel ideas and flexible thinking. This perspective introduced creativity as a crucial cognitive function within the broader context of intelligence and learning.

Getzels and Jackson believed that all individuals have the potential for creative thought, especially in situations that challenge them to think beyond established solutions. Thus, creativity is not limited to traditionally “creative” fields like art but is relevant across disciplines and daily life situations.

Intelligence and Creativity

Getzels and Jackson made a key distinction between intelligence and creativity, proposing that while the two are interconnected, they remain distinct constructs with unique roles in problem-solving. Traditional intelligence, as measured by IQ tests, focuses on logical reasoning, factual knowledge, and memory. Creativity, however, involves approaching problems with originality, openness, and non-linear thinking.

By differentiating between intelligence and creativity, Getzels and Jackson laid the groundwork for understanding how these constructs interact to influence an individual’s ability to solve problems innovatively. This concept also reshaped how educators and psychologists approached giftedness and talent, recognizing that creative potential could exist independently of high IQ scores.

Divergent and Convergent Thinking

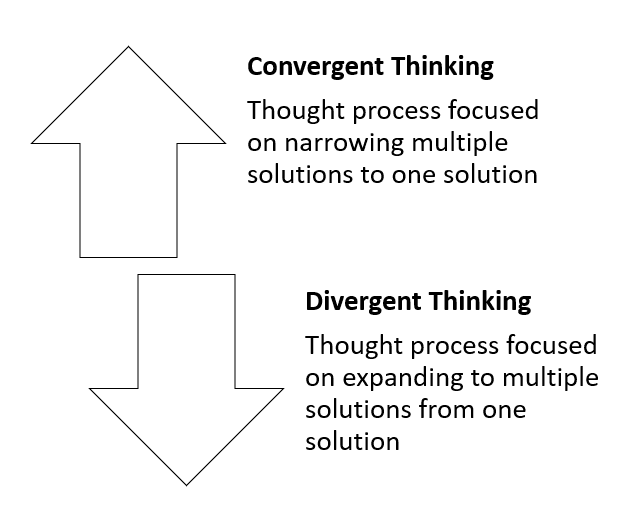

Getzels and Jackson incorporated concepts of divergent and convergent thinking into their model. This distinction, initially introduced by J.P. Guilford, describes two types of cognitive processes that contribute to creativity.

- Divergent Thinking- Divergent thinking involves generating multiple ideas or potential solutions to a problem. It is the process behind brainstorming and exploring various possibilities without restricting oneself to conventional solutions.

- Convergent Thinking- Convergent thinking, by contrast, involves analyzing and selecting the best solution from a range of ideas. It relies on critical evaluation and decision-making, narrowing down choices to arrive at the most effective solution.

Divergent vs Convergent Production

In creative problem-solving, individuals must balance both thinking styles. Getzels and Jackson argued that the creative process requires an initial phase of divergent thinking to explore a wide range of ideas, followed by convergent thinking to refine and implement the best solution. This dynamic interplay of divergent and convergent thinking is fundamental to creative processes in problem-solving.

Read More- Divergent and Convergent Reasoning

Complex and Ill-Defined Problems

According to Getzels and Jackson, true creativity often manifests when individuals confront complex, ambiguous, or ill-defined problems. These problems lack straightforward answers and require unconventional thinking and an openness to alternative perspectives.

Unlike simple problems, which can be solved using rote learning or procedural knowledge, complex problems demand flexibility, adaptability, and resilience—qualities inherent to creative thinking. They posited that creativity flourishes in such situations because individuals are pushed to explore ideas that may not initially seem viable, allowing for unexpected insights and innovative solutions. This insight broadened the scope of creativity research, demonstrating that creativity is not limited to artistic expression but is integral to effective problem-solving in real-world situations.

Types of Problems (Raami, 2019)

Read More- Problem Solving

Creativity as a Dynamic and Context-Dependent Process

Getzels and Jackson viewed creativity as a dynamic process shaped by both individual cognitive abilities and the environmental context. They argued that creativity does not arise in isolation but rather through interaction with the environment, social context, and the specific characteristics of the problem at hand.

This emphasis on context highlighted that creativity could be cultivated and encouraged through the right circumstances and support systems. For instance, educational environments that promote autonomy, curiosity, and open-ended inquiry are more likely to foster creative problem-solving than rigid, structured settings. By identifying creativity as a context-sensitive process, Getzels and Jackson underscored its malleability, suggesting that creative potential could be enhanced through exposure to diverse experiences, novel challenges, and opportunities for exploration.

Strengths

The strengths of this theory includes-

Strengths of the Approach

- Recognition of Creativity as Distinct from Intelligence- One of the key contributions of Getzels and Jackson’s work is its recognition of creativity as a separate construct from traditional intelligence. They emphasized that creativity is not solely dependent on cognitive intelligence, broadening the view of human abilities beyond traditional IQ measures (Getzels & Jackson, 1962). This distinction allowed educators and researchers to better identify and nurture creative abilities in individuals who may not excel on conventional intelligence tests (Baer, 2011).

- Emphasis on Divergent and Convergent Thinking- By distinguishing between divergent and convergent thinking, Getzels and Jackson provided a framework to understand the creative process in problem-solving situations. Divergent thinking fosters the generation of multiple ideas, while convergent thinking involves refining these ideas into a viable solution (Getzels & Jackson, 1962). This dual approach has since been supported in creativity research and remains central to models like Guilford’s SOI, which also emphasizes the value of both types of thinking (Runco, 2014).

- Contextual Sensitivity of Creativity- Their approach highlights the importance of context in shaping creativity, which supports the idea that creativity can be cultivated through enriched environments (Lubart, 2001). Recognizing that external factors, such as educational settings or organizational culture, impact creativity has led to practical applications in designing environments that foster creativity, such as workplaces that encourage autonomy and open-ended problem-solving (Hunter, Bedell, & Mumford, 2007).

- Encouragement of Broader Giftedness Identification- By showing that creativity and intelligence are interconnected yet distinct, Getzels and Jackson encouraged a more inclusive approach to identifying giftedness (Baer & Kaufman, 2019). This model helped to broaden the definition of giftedness, promoting creativity as an equally valuable form of talent, especially in educational systems that traditionally prioritize IQ and academic achievement.

Weaknesses

The weaknesses of the theory includes-

Weaknesses of the Approach

- Lack of Empirical Evidence on Creativity and Intelligence Interaction- While Getzels and Jackson posited that intelligence and creativity are interconnected, subsequent research has struggled to consistently demonstrate how the two interact (Kozbelt, Beghetto, & Runco, 2010). Some studies suggest that high intelligence supports creativity only up to a certain threshold, beyond which they operate independently (Simonton, 2000). Thus, the precise nature of this interaction remains unclear and may not be as universally applicable as their theory suggests.

- Limited Operational Definitions- Getzels and Jackson did not provide concrete operational definitions for key components like “complex problem-solving” or “ambiguous problems,” which has led to challenges in replicating and testing their model. These vague terms make it difficult to measure creativity reliably and accurately in empirical studies, which limits the practical application of their theory (Plucker & Renzulli, 1999). Without clearer definitions, assessing creativity remains challenging in standardized contexts.

- Reliance on Problem-Solving Contexts- The focus on problem-solving contexts may overlook creative processes that occur outside of problem-solving. For example, artistic creativity often emerges from personal expression rather than a need to solve a specific problem. This limitation means that Getzels and Jackson’s theory may not fully capture the diversity of creative experiences, potentially limiting its application in fields like the arts (Sternberg, 2006).

- Overemphasis on Cognitive Processes- Getzels and Jackson’s model places significant emphasis on cognitive processes, potentially downplaying other factors influencing creativity, such as motivation, personality traits, and emotional states (Amabile, 1996). While cognitive processes like divergent and convergent thinking are important, research suggests that creativity also relies heavily on factors like intrinsic motivation and risk-taking, which their model does not address (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996).

Conclusion

Getzels and Jackson’s approach to creativity brought forth a revolutionary understanding of intelligence and problem-solving, suggesting that creativity is an integral component of human cognition that plays a central role in addressing complex problems. Their two-factor model, which distinguishes but connects intelligence and creativity, challenges traditional views of intelligence as a singular measure and underscores the multifaceted nature of cognitive abilities.

By emphasizing problem-solving as the context where creativity emerges, they highlighted the significance of both divergent and convergent thinking, showing that creativity is essential in generating and refining ideas. Their work emphasizes that creativity is not merely a personality trait but a skill that can be developed and cultivated, especially in environments that support exploration and innovation.

The model’s impact on education, talent identification, and professional development underscores its enduring relevance, promoting a comprehensive view of human potential that values both intellect and creativity.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in Context: Update to “The Social Psychology of Creativity”. Westview Press.

Baer, J. (2011). Creativity and Divergent Thinking: A Task-Specific Approach. Psychology Press.

Baer, J., & Kaufman, J. C. (2019). Creativity and Reason in Cognitive Development. Cambridge University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. Harper Perennial.

Getzels, J. W., & Jackson, P. W. (1962). Creativity and Intelligence: Explorations with Gifted Students. Wiley.

Hunter, S. T., Bedell, K. E., & Mumford, M. D. (2007). Climate for creativity: A quantitative review. Creativity Research Journal, 19(1), 69-90.

Kozbelt, A., Beghetto, R. A., & Runco, M. A. (2010). Theories of creativity. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity (pp. 20-47). Cambridge University Press.

Lubart, T. I. (2001). Models of the creative process: Past, present and future. Creativity Research Journal, 13(3-4), 295-308.

Plucker, J. A., & Renzulli, J. S. (1999). Psychometric approaches to the study of human creativity. Handbook of Creativity, 35-61.

Runco, M. A. (2014). Creativity: Theories and Themes: Research, Development, and Practice. Academic Press.

Raami, A. (2019). Towards solving the impossible problems. Sustainability, human well-being, and the future of education, 201.

Simonton, D. K. (2000). Creativity: Cognitive, personal, developmental, and social aspects. American Psychologist, 55(1), 151-158.

Sternberg, R. J. (2006). The Nature of Creativity: Contemporary Psychological Perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 18,509 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, November 3). Getzels and Jackson’s Theory of Creative Thinking- 4 Strengths of the Theory. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/getzels-and-jacksons-theory/