Introduction

Cognitive impairment and dementia are among the most pressing neuropsychological concerns of the 21st century. Dementia refers to a group of progressive neurological disorders characterized by deterioration in memory, language, reasoning, executive functions, and social behavior severe enough to interfere with daily functioning (Carson, Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2007). Cognitive impairment, by contrast, is a broader construct that includes both mild and severe forms of cognitive decline and may result from aging, psychiatric conditions, or neurological injury (Barlow & Durand, 1999).

The assessment of dementia and cognitive impairment serves several critical purposes. It assists in distinguishing normal aging from pathological decline, guides treatment planning, aids differential diagnosis, and provides a baseline for longitudinal monitoring (Lezak, 1995). This process is inherently interdisciplinary, drawing from clinical psychology, neurology, psychiatry, and psychometrics.

Read More: Mental Health

Conceptual Framework of Dementia and Cognitive Impairment

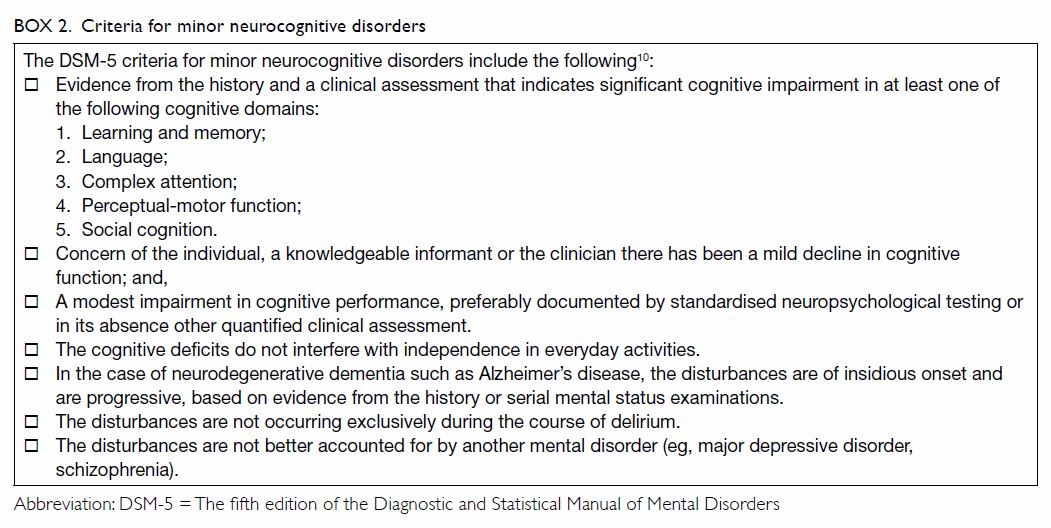

From the perspective of abnormal psychology, dementia has traditionally been conceptualized as an organic brain disorder associated with structural and functional neural degeneration (Davison, Neal, & Kring, 2004). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) uses the term “Major Neurocognitive Disorder,” reflecting a shift from purely medical to cognitive-functional models. Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), a transitional stage between normal aging and dementia, involves measurable cognitive decline that does not yet severely impact daily life (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004).

Dementia

Cognitive impairment encompasses deficits across multiple domains, including:

- Attention and processing speed

- Learning and memory

- Language and communication

- Executive functioning

- Visuospatial and perceptual-motor abilities

Lezak (1995) emphasized that these domains are interconnected, reflecting complex neural networks underlying cognition and behavior.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

According to Kaplan, Sadock, and Grebb (1994), the etiology of dementia is multifactorial, involving neurodegenerative, vascular, traumatic, and infectious causes. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common etiology, followed by vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. The neuropathology involves the accumulation of β-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuronal loss, particularly in the hippocampus and cortical association areas.

From a psychological viewpoint, Alloy, Riskind, and Manos (2005) argue that cognitive impairment also interacts with emotional and environmental factors. Depression, anxiety, and social isolation can exacerbate cognitive deficits, leading to diagnostic complexities in clinical practice. Taylor (2006) and Brannon and Feist (2007) highlight the role of health psychology in understanding how behavioral, lifestyle, and stress-related factors contribute to cognitive aging.

Principles of Cognitive Assessment

Cognitive assessment involves the systematic evaluation of mental processes through standardized psychological tests, clinical interviews, behavioral observations, and collateral information. As Anastasi and Urbina (2005) note, the purpose of psychological testing is not merely to label or diagnose but to measure specific aspects of cognitive functioning objectively and reliably.

Lezak (1995) proposed that effective assessment of dementia should meet three criteria:

- Comprehensiveness: Covering all major cognitive domains.

- Comparability: Using standardized norms adjusted for age, education, and culture.

- Clinical relevance: Linking test results to real-world functioning.

The assessment process typically begins with screening tests followed by detailed neuropsychological evaluation when impairment is suspected.

Screening Instruments

3 of the key screening instruments include:

1. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

The MMSE is one of the most widely used cognitive screening tools. It assesses orientation, attention, memory, language, and visuospatial skills (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975, as cited in Lezak, 1995). Scores below 24 out of 30 often indicate possible cognitive impairment. Despite its popularity, the MMSE has limitations related to educational bias and insensitivity to early or mild deficits.

2. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

Developed to detect mild cognitive impairment, the MoCA includes more complex tasks of executive function, abstraction, and delayed recall. Research indicates higher sensitivity compared to MMSE, making it valuable in early dementia detection (Lezak, 1995; Carson et al., 2007).

3. Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE and ACE-III)

ACE and its revised versions provide comprehensive assessment across five domains: attention, memory, verbal fluency, language, and visuospatial function. The ACE-III has been particularly useful in differentiating Alzheimer’s disease from frontotemporal dementia.

ACE

Comprehensive Neuropsychological Assessment

When screening tools suggest impairment, a full neuropsychological assessment is conducted. According to Lezak (1995) and Wolman (1975), such evaluation seeks to map cognitive profiles, identify strengths and weaknesses, and understand how brain pathology translates into functional deficits.

Memory Assessment

Tests such as the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS) and Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) evaluate immediate, delayed, and recognition memory. Dementia often shows rapid forgetting, whereas in depression, retrieval rather than storage is impaired (Davison et al., 2004).

Attention and Executive Function

Tasks such as the Trail Making Test (TMT), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), and Stroop Test measure flexibility, planning, and inhibitory control. Deficits in these domains are pronounced in frontal and subcortical dementias.

Language and Visuospatial Functions

Confrontation naming tests, semantic fluency tasks, and clock-drawing tests assess cortical functions related to the temporal and parietal lobes (Barlow & Durand, 1999). Visuospatial impairment, such as misperceiving distances or reproducing shapes, often signals right parietal lobe dysfunction.

Functional Assessment

In addition to cognitive testing, assessment of daily functioning (e.g., using the Activities of Daily Living Scale) is essential to evaluate real-world impact (Sundberg, Winebarger, & Taplin, 2002).

Cultural and Contextual Considerations

Cultural, linguistic, and educational factors significantly influence assessment outcomes. In the Indian context, Kapur (1995) emphasized the need for culturally adapted tests to ensure validity. Western tests often assume literacy, urban exposure, and specific cultural knowledge, which can disadvantage individuals from diverse backgrounds. Therefore, indigenously developed tools, such as the NIMHANS Neuropsychology Battery, have been crucial in ensuring accurate diagnosis within non-Western populations.

Differential Diagnosis

Cognitive impairment is not exclusive to dementia. Psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia can produce pseudo-dementia, mimicking organic decline (Rychlak, 1973). Kellerman and Burry (1981) caution that misinterpretation of test data without contextual understanding can lead to misdiagnosis. Hence, assessment must integrate neuropsychological results with medical history, psychiatric evaluation, and neuroimaging findings.

Role of Clinical and Health Psychologists

According to Sundberg et al. (2002), the psychologist’s role in dementia assessment extends beyond testing—it includes communication of findings, caregiver counseling, and rehabilitation planning. Health psychologists, as noted by Taylor (2006), focus on behavioral interventions that maintain cognitive health, such as cognitive training, physical activity, and stress reduction.

Brannon and Feist (2007) further highlight the psychosocial implications of dementia diagnosis—patients often experience anxiety, stigma, and loss of autonomy. Thus, ethical assessment practices must prioritize patient dignity, informed consent, and feedback in understandable terms.

Ethical and Professional Issues

Anastasi and Urbina (2005) underscore that test results must be interpreted cautiously, considering measurement error and normative context. Ethical principles from the American Psychological Association emphasize competence, confidentiality, and cultural sensitivity in assessment.

In cases where dementia leads to legal or occupational implications (e.g., driving competence, financial management), psychologists must navigate complex ethical terrain, balancing patient rights with societal safety (Kaplan et al., 1994).

Advances in Cognitive Assessment

Recent years have seen integration of computerized cognitive testing, neuroimaging, and biomarkers to complement traditional assessment. Digital platforms allow for precise measurement of response times and patterns, enhancing diagnostic sensitivity. However, as Sarason and Sarason (2005) warn, technology should not replace clinical judgment; interpretation must remain grounded in psychological theory and human understanding.

Emerging research also supports the use of ecological validity measures—tasks that simulate real-world cognitive challenges (Lezak, 1995). These approaches provide more accurate predictions of functional outcomes than decontextualized laboratory tests.

Interventions and Clinical Implications

Assessment results guide intervention strategies, including cognitive rehabilitation, environmental modification, and caregiver support. Barlow and Durand (1999) emphasize that timely assessment enables early intervention, potentially delaying progression or mitigating impact. Interventions often focus on enhancing residual skills, compensatory strategies, and promoting neuroplasticity through structured cognitive exercises.

Health psychology principles, such as stress management, social engagement, and lifestyle modification, complement clinical interventions by addressing risk factors for cognitive decline (Taylor, 2006; Brannon & Feist, 2007).

Conclusion

Assessment of dementia and cognitive impairment stands at the intersection of psychology, neuroscience, and medicine. It requires not only technical skill in test administration but also interpretive sensitivity to the human experience of cognitive decline. Grounded in decades of research and theory (Lezak, 1995; Sarason & Sarason, 2005; Carson et al., 2007), the process of cognitive assessment continues to evolve with advances in neuropsychology, psychometrics, and health psychology. As the global population ages, comprehensive, culturally responsive, and ethically sound cognitive assessment will remain essential for promoting mental health, dignity, and quality of life among individuals facing cognitive challenges.

References

Alloy, L. B., Riskind, J. H., & Manos, M. J. (2005). Abnormal Psychology: Current perspectives (9th ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill.

Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (2005). Psychological Testing (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (1999). Abnormal Psychology (2nd ed.). Books/Cole.

Brannon, L., & Feist, J. (2007). Introduction to Health Psychology. Thomson Wadsworth.

Carson, R. C., Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (13th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Davison, G. C., Neal, J. M., & Kring, A. M. (2004). Abnormal Psychology (9th ed.). Wiley.

Kaplan, H. I., Sadock, B. J., & Grebb, J. A. (1994). Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry (7th ed.). B.I. Waverly Pvt. Ltd.

Kapur, M. (1995). Mental Health of Indian Children. Sage Publications.

Kellerman, H., & Burry, A. (1981). Handbook of Diagnostic Testing: Personality Analysis and Report Writing. Grune & Stratton.

Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological Assessment. Oxford University Press.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). Abnormal Psychology (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill.

Rychlak, F. (1973). Introduction to Personality and Psychopathology. Houghton Muffin.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (2005). Abnormal Psychology. Dorling Kindersley.

Sundberg, N. D., Winebarger, A. A., & Taplin, J. R. (2002). Clinical Psychology: Evolving Theory, Practice and Research. Prentice-Hall.

Taylor, S. (2006). Health Psychology. Tata McGraw-Hill.

Wolman, B. B. (1975). Handbook of Clinical Psychology. McGraw Hill.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 24). 3 Important Dementia and Cognitive Impairment Assessment. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/dementia-and-cognitive-impairment-assessment/