Introduction

Noam Chomsky is one of the most prominent intellectuals in the fields of linguistics and cognitive psychology, particularly known for his revolutionary theories on language acquisition and development. His approach, often referred to as a nativist theory, posits that humans are biologically predisposed to acquire language. Chomsky argued that we are innately endowed with the cognitive structures necessary for understanding and producing language, rather than learning it solely through interaction with the environment, as behaviorists had previously suggested.

Chomsky’s theory is built upon several key concepts. One of the most influential is ‘Transformational Grammar’, introduced in his seminal work Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965). This theory distinguishes between surface structure- the outward form of sentences, and deep structure- the abstract, underlying principles that govern sentence formation.

By examining how sentences with different surface structures can derive from the same deep structure, Chomsky illuminated the complexity of linguistic processing and the universality of underlying grammatical principles.

Central to Chomsky’s argument is the notion of Universal Grammar, which posits that all human languages share a common structural basis. This innate set of linguistic principles enables humans to effortlessly acquire language, regardless of their specific linguistic environment. Chomsky’s emphasis on the innate aspects of language acquisition has led to a deeper understanding of the cognitive mechanisms underlying linguistic competence and has sparked extensive research and debate within the fields of linguistics and cognitive psychology.

Chomsky’s groundbreaking ideas emerged during a period when behaviorism dominated psychology, with theories focusing on observable behaviors and conditioning processes. He challenged this paradigm, particularly the view that language is merely a learned behavior reinforced through repetition and rewards.

Instead, Chomsky proposed that all humans are born with an internal Language Acquisition Device (LAD), a theoretical construct that enables the rapid learning and understanding of language structures. This theory explains why children, regardless of cultural background, tend to develop language in remarkably similar ways and at similar stages.

Understanding Chomsky’s theory also requires a grasp of some basic elements of language. Language is composed of various components, such as-

• Phonemes – the basic unit of language which includes sounds like “a” or “th”.

• Morpheme – the basic unit of meaning in a language, Ex- “unkindly” has three morphemes in it- un, kind, and -ly.

• Syntax – the rules that govern sentence structure. It focuses on how words are organised into sentences.

• Semantics – the meaning of words and sentences.

• Pragmatics – the use of language is a culturally appropriate manner.

Chomsky’s theory primarily delt with the syntax. He believed that it was important to examine the structure that lay below the surface level language.

Transformational Grammar

In his seminal work Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965), Noam Chomsky revolutionized our understanding of language with the introduction of Transformational Grammar. Central to this theory is the distinction between surface structure and deep structure, two layers that represent how sentences are formed and understood.

• Surface structure is the explicit form of a sentence—the sequence of words as it is spoken, written, or read. It corresponds to what we encounter in communication and reflects the actual syntactic arrangement of words.

• Deep structure, on the other hand, refers to the abstract, underlying level of syntactic and semantic relationships that determine the meaning of the sentence. It represents the core grammatical relationships between elements like the subject, verb, and object, which remain consistent across different sentence variations.

Chomsky argued that speakers of a language have the innate ability to transform deep structures into various surface structures through transformational rules. These rules explain how we can express the same fundamental idea using different grammatical constructions. For example, the sentences-

• I fed the cat.

• The cat was fed by me.

Though different in their surface structures (active vs. passive voice), both sentences share the same deep structure. They express the same action: that a person (subject) fed a cat (object). Transformational grammar allows us to understand how such different forms can convey the same message.

Chomsky’s theory extends far beyond this simple example. Transformational rules enable the generation of complex sentence forms, such as questions, negatives, and embedded clauses, all based on an underlying deep structure. For instance:

• “I fed the cat” can be transformed into the question, “Did I feed the cat?”

• “The cat was fed by me” can be transformed into “Was the cat fed by me?”

These transformations demonstrate that language is not just a linear combination of words but rather a dynamic process involving abstract mental rules. The concept of transformations explains how sentences can undergo structural changes—such as converting an active sentence to passive, forming questions, or rearranging word orders—while maintaining their deep structure, or core meaning.

Furthermore, Chomsky’s theory suggests that the human brain contains a specialized language faculty—an innate system that enables speakers to generate and interpret sentences. This faculty operates independently of other cognitive functions and processes language at a deep level, often without conscious effort. For example, when we process a sentence like “The cat was fed by me,” our language faculty understands the underlying relationship between the subject and object even though the sentence presents them differently compared to the active form “I fed the cat.”

This ability to parse both simple and complex sentences, regardless of their surface variations, underscores Chomsky’s claim that language involves an innate, universal set of rules that guide sentence formation and interpretation across all human languages. His theory of Universal Grammar posits that these rules are shared by all languages, though the specific transformational rules may vary from one language to another.

Transformational Grammar fundamentally reshaped the field of linguistics by shifting the focus from the observable structure of sentences to the underlying principles and cognitive mechanisms that generate language. Chomsky’s insights not only illuminated how we can transform sentences but also deepened our understanding of the inherent capabilities of the human mind in language acquisition and use.

Language Acquisition Device

One of the most controversial and radical ideas proposed by Noam Chomsky is his theory of innate linguistic structures, which fundamentally challenges previous notions of language acquisition. He believed that learning language was innate because of a biological language acquisition device.

Language Acquisition Device is a theoretical construct which refers to an innate mental mechanism that enables humans to acquire language naturally and efficiently. Central to Chomsky’s argument is what he refers to as the “poverty of the stimulus” argument.

Chomsky posits that although children are exposed to various language stimuli, this exposure alone is insufficient for them to fully master the complexities of language. Despite the limited input, children consistently manage to produce and understand novel sentences, which suggests that there is more to language acquisition than mere exposure.

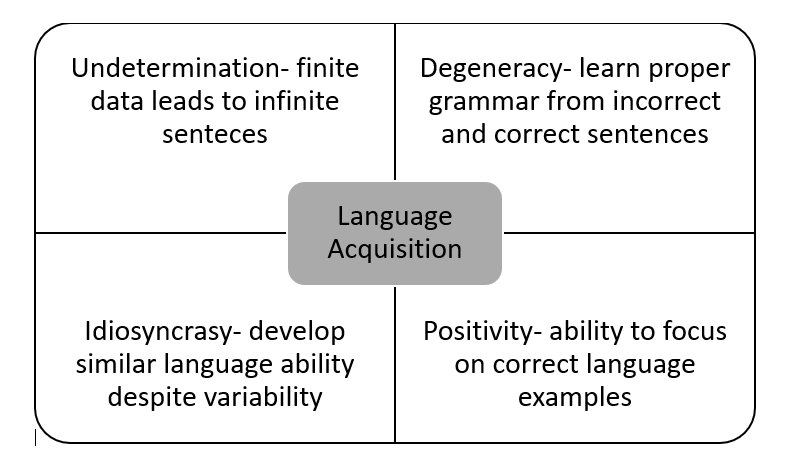

Chomsky’s theory is supported by several key arguments that reinforce his position. First, the argument of idiosyncrasies addresses the unique and highly variable nature of the linguistic stimuli that children encounter. Children are exposed to a wide range of language input from different speakers, in various contexts, and with differing levels of clarity. This input is often inconsistent and contains numerous irregularities.

For example, the language used by different individuals can vary in dialect, accent, or even the grammatical structures employed. If language acquisition were solely dependent on these external inputs, the significant variability and idiosyncrasies would make it extremely difficult for children to acquire a consistent and coherent understanding of language. However, despite this variability, children still manage to learn and use language effectively, suggesting that there is an innate capacity for language that helps them navigate these inconsistencies.

Second, the concept of undetermination highlights the problem of incomplete and ambiguous linguistic input. The language data that children receive is often incomplete and ambiguous.

For instance, children may hear only partial sentences or sentences with grammatical errors. They may not be exposed to every possible grammatical construction or all the rules of the language. Despite this, children are able to infer and internalize complex grammatical rules. This suggests that the linguistic input alone is insufficient, and there must be an inherent cognitive structure that allows children to deduce the underlying principles of language.

Further supporting Chomsky’s theory is the idea of degeneracy. This concept refers to the ability of children to rapidly learn the correct grammatical structures despite initially producing incorrect sentences. Children often make grammatical errors when they are learning to speak, but they quickly adjust their language use based on feedback. This rapid correction process indicates that they have an internalized understanding of grammatical rules that enables them to refine their language skills. The ability to swiftly learn from mistakes and adopt correct forms of language suggests that there is an innate mechanism guiding their acquisition process.

Lastly, the positivity argument suggests that children are not just learning from incorrect examples but are guided by positive instances of language usage. Children focus on and internalize the correct forms of language, rather than learning from the errors they encounter. This selective attention to positive examples helps them form grammatically accurate sentences and reinforces the notion that there is an innate linguistic capability that directs their learning process.

Together, these arguments present a compelling case for Chomsky’s theory, which proposes that the capacity for language acquisition is hardwired into the human brain, challenging the notion that language is solely a product of environmental exposure.

Fig 1 Cognitive Evidence for Chomsky’s Theory

Cognitive Evidence for Chomsky’s Theory

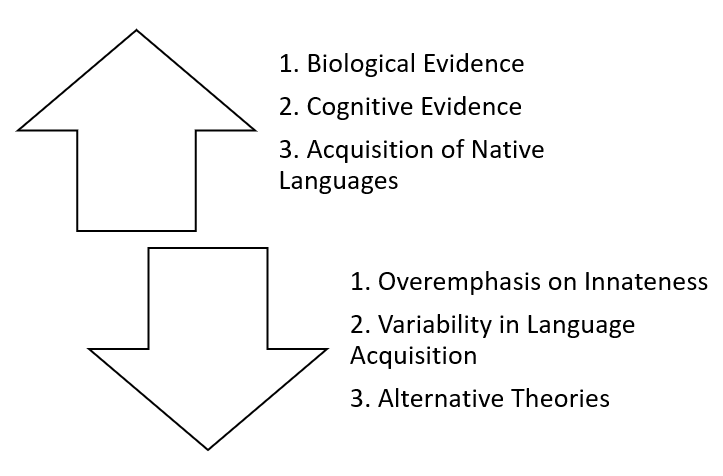

Support for Chomsky’s Theory

- Biological Evidence- The existence of dedicated brain regions such as Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area for language suggests that the human brain is biologically predisposed to acquire and process language (Pinker, 1994). Damage to this area often results in Broca’s aphasia, characterized by difficulties in speech production and grammatical structuring, yet comprehension remains relatively intact. Wernicke’s area, located in the left temporal lobe, is essential for language comprehension. Damage here leads to Wernicke’s aphasia, where individuals can produce fluent but often nonsensical speech and have trouble understanding language. This localization supports Chomsky’s theory that language acquisition involves innate cognitive mechanisms, as the brain’s specialized areas for language suggest that the capacity for language is hardwired.

- Cognitive Evidence- as mentioned above, Underdetermination suggests that the limited data children receive allows them to generate an infinite number of sentences. Degeneracy refers to children’s ability to learn proper grammar despite exposure to incomplete or incorrect sentences. Idiosyncrasy indicates that children develop similar language abilities despite varying exposure. Positivity shows that children focus on correct language examples and do not learn from incorrect sentences. These factors point to an innate mechanism that helps children deduce grammatical rules from limited input (Sobecks, 2020).

- Acquisition of Native Languages- Children of migrants or displaced adults often learn new languages rapidly, even with minimal exposure. This phenomenon is exemplified by the development of creole languages in the Caribbean. During the era of slavery, children of enslaved people quickly acquired the “pidgin” language that emerged from their parents’ limited exposure to European languages, despite its rudimentary nature (Bickerton, 1984). This ability to assimilate and adapt to new linguistic environments highlights the remarkable capacity of children to acquire and master languages under diverse and challenging circumstances.

Criticism to Chomsky’s Theory

- Overemphasis on Innateness– Critics argue that Chomsky’s LAD theory places too much emphasis on the innate aspects of language acquisition and does not sufficiently account for the role of social interaction and learning environments (Slama-Cazacu, 1976). The theory suggests that children have an inborn ability to acquire language, but this overlooks the significant role that exposure to and interaction with language in context plays in linguistic development.

- Variability in Language Acquisition- The LAD theory struggles to account for the variability in language acquisition among children. Differences in language learning rates, styles, and outcomes can be influenced by a range of factors beyond innate abilities, such as cultural and environmental influences (Sampson, 1989). This variability challenges the notion of a universal, innate language mechanism.

- Alternative Theories– Cognitive and social interactionist theories offer compelling alternatives to Chomsky’s LAD theory. These approaches emphasize the role of general cognitive abilities and social interaction in language development. For instance, statistical learning and social feedback mechanisms provide explanations for how children acquire language that do not rely on an innate language device, suggesting that language learning can be explained through more general cognitive processes and environmental factors.

Fig 2- Overview of Critique to the Theory

Evidence to Support and Criticize the Theory

Conclusion

Noam Chomsky’s theories on language acquisition, particularly the concept of the Language Acquisition Device (LAD) and Transformational Grammar, have profoundly influenced our understanding of linguistic development. By proposing that language acquisition is guided by an innate cognitive mechanism, Chomsky challenged the behaviorist view that language is learned solely through environmental interactions and conditioning. His ideas introduced the notion of Universal Grammar, suggesting that all humans possess an inherent ability to understand and produce language structures.

Chomsky’s emphasis on innate linguistic structures has been supported by various forms of evidence, including biological findings related to specialized brain regions for language and cognitive phenomena such as the poverty of the stimulus, degeneracy, and positivity. These factors illustrate how children can acquire complex grammatical rules despite limited and variable linguistic input.

Chomsky’s theories have provided a foundational framework for understanding language acquisition, ongoing research and debate continue to refine our comprehension of how language is acquired. The interaction between innate abilities and environmental influences remains a central focus in the study of linguistics and cognitive psychology.

Reference

Bickerton, D. (1984). The language bioprogram hypothesis. Behavioral and brain sciences, 7(2), 173-188.

Farmer, T. A., & Matlin, M. W. (2019). Cognition. John Wiley & Sons.

Galotti, K. M. (2018). Cognitive psychology in and out of the laboratory. Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.

Pinker, S. (1994). On language. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 6(1), 92-98.

Sampson, G. (1989). Language acquisition: growth or learning?. Philosophical papers, 18(3), 203-240.

Slama-Cazacu, T. (1976). The role of social context in language acquisition. Language and Man. Anthropological Issues, S, 127-147.

Sobecks, B. (2020). Language Acquisition Device and the Origin of Language. Brain Matters, 2(1), 9-11.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 18,526 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, September 6). Chomsky’s Revolutionary Theory of Language Acquisition- Supported by 3 Arguments!. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/chomskys-theory-of-language-acqisition/