Introduction

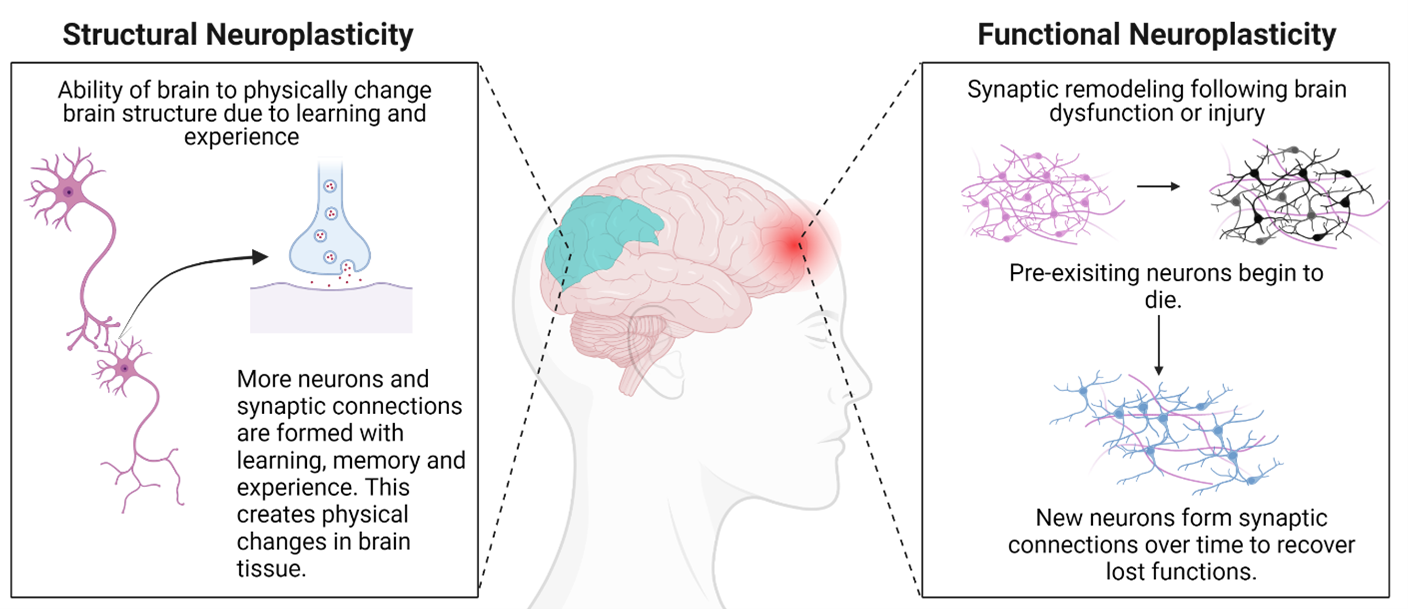

Cognitive rehabilitation is a structured therapeutic process aimed at restoring or compensating for impaired cognitive functions following brain injury, neurological disease, or psychiatric conditions. It encompasses a range of techniques designed to improve processes such as attention, memory, executive functioning, and problem-solving (Lezak, 1995). The concept rests on the brain’s ability to reorganize itself—a principle known as neuroplasticity—and has become central to modern neuropsychological and clinical interventions (Barlow & Durand, 1999). Through targeted exercises, compensatory strategies, and environmental modifications, cognitive rehabilitation helps individuals regain autonomy and adapt to everyday life challenges.

Neuroplasticity

Read More: Neuropsychological Rehabilitation

Concept and Goals of Cognitive Rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation (CR) has evolved from early neuropsychological interventions that focused primarily on retraining lost abilities to a more holistic, multidimensional approach. The primary goals of CR are to restore impaired cognitive functions, compensate for deficits through alternative strategies, and enhance psychological adjustment and quality of life (Davison, Neal, & Kring, 2004). According to Sarason and Sarason (2005), rehabilitation must address both the cognitive and emotional consequences of brain dysfunction to achieve lasting improvements.

Cognitive rehabilitation typically includes two major approaches:

- Restorative (Retraining) Approach – This method emphasizes repetitive practice and drill-based tasks aimed at re-establishing specific cognitive skills. For example, memory drills, attention training, and computerized exercises help strengthen neural connections (Lezak, 1995).

- Compensatory (Adaptive) Approach – This focuses on teaching patients to use external aids or behavioral strategies, such as using diaries, reminders, or mnemonic devices, to overcome persistent deficits (Anastasi & Urbina, 2005).

Both approaches are often combined in clinical settings, depending on the severity and type of cognitive impairment. The ultimate goal is to enhance daily functioning, enabling patients to engage in work, social, and personal activities despite their limitations (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004).

Applications in Clinical Psychology

Cognitive rehabilitation is most commonly used in the treatment of individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, dementia, schizophrenia, and major depressive disorder (Carson, Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2007). Each condition presents unique cognitive challenges requiring tailored interventions.

For instance, memory rehabilitation often employs errorless learning techniques, spaced retrieval, and environmental structuring to improve recall (Lezak, 1995). Similarly, attention training might include exercises such as sustained attention tasks or computerized cognitive drills. In psychiatric populations, cognitive remediation programs have shown effectiveness in improving attention and working memory, particularly among patients with schizophrenia (Sarason & Sarason, 2005).

According to Wolman (1975), rehabilitation is not merely about restoring lost cognitive capacities but also about facilitating emotional adjustment, self-efficacy, and motivation. Cognitive impairments often co-occur with mood disorders such as depression and anxiety, which can exacerbate functional deficits. Therefore, a successful rehabilitation plan must integrate psychotherapeutic support alongside cognitive exercises (Taylor, 2006).

Techniques and Methods of Cognitive Rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation employs a diverse set of techniques depending on the target domain. These include:

- Memory Retraining: Repetition, categorization, and association methods are used to strengthen encoding and retrieval processes (Kapur, 1995).

- Attention Training: Techniques like attention process training (APT) focus on enhancing sustained, selective, and divided attention (Lezak, 1995).

- Executive Function Training: Strategies such as goal management training (GMT) help individuals improve planning, organization, and impulse control (Sundberg, Winebarger, & Taplin, 2002).

- Metacognitive Strategies: These involve increasing awareness of one’s cognitive deficits and developing self-regulatory techniques to manage them (Brannon & Feist, 2007).

Classification of Memory Rehabilitation Techniques

Technological advancements have also contributed to modern CR through computer-assisted cognitive training programs, virtual reality environments, and mobile-based cognitive exercises, offering engaging and flexible options for rehabilitation (Barlow & Durand, 1999).

Theoretical Foundations

Cognitive rehabilitation is grounded in theories of learning, neuroplasticity, and behavioral psychology. The behavioral learning theory suggests that repeated practice strengthens neural pathways, reinforcing adaptive cognitive responses (Alloy, Riskind, & Manos, 2005). From a cognitive perspective, rehabilitation leverages information-processing models that conceptualize cognition as a sequence of mental operations—attention, encoding, storage, and retrieval—each of which can be trained or compensated (Sarason & Sarason, 2005).

Moreover, health psychology contributes to the theoretical framework of CR by emphasizing the role of psychosocial factors, motivation, and coping mechanisms in recovery (Taylor, 2006). Patients’ beliefs about their ability to recover significantly influence rehabilitation outcomes. Thus, integrating motivational enhancement and behavioral reinforcement can improve adherence and effectiveness.

Effectiveness and Challenges

Evidence from neuropsychological and clinical research supports the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation in enhancing cognitive performance and daily functioning (Lezak, 1995; Carson et al., 2007). However, outcomes vary depending on the severity of brain damage, the timing of intervention, and individual differences in age, motivation, and education.

One of the main challenges in cognitive rehabilitation lies in generalization—the transfer of trained cognitive skills to real-world situations. Patients may show improvement in structured test conditions but fail to apply these gains in everyday activities (Davison et al., 2004). Therefore, rehabilitation programs must incorporate ecologically valid tasks that mirror real-life contexts and emphasize functional adaptation over mere test performance (Wolman, 1975).

Additionally, the cultural context of the individual plays a crucial role. As Kapur (1995) and Sarason & Sarason (2005) highlight, culturally adapted interventions are essential to ensure that cognitive training methods are relevant and accessible across diverse populations.

Conclusion

Cognitive rehabilitation represents a vital interface between clinical psychology, neuropsychology, and health psychology, offering hope to individuals affected by cognitive impairments. Through evidence-based, individualized interventions, it promotes not only cognitive recovery but also emotional and social reintegration. The success of rehabilitation depends on a comprehensive understanding of neuropsychological mechanisms, cultural context, and the human capacity for adaptation. As psychological science advances, cognitive rehabilitation continues to evolve—bridging the gap between brain function and meaningful living.

References

Alloy, L. B., Riskind, J. H., & Manos, M. J. (2005). Abnormal Psychology: Current Perspectives (9th ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill: New Delhi.

Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (2005). Psychological Testing (7th ed.). Pearson Education: India.

Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (1999). Abnormal Psychology (2nd ed.). Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole.

Brannon, L., & Feist, J. (2007). Introduction to Health Psychology. Thomson Wadsworth: Singapore.

Carson, R. C., Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (13th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Davison, G. C., Neal, J. M., & Kring, A. M. (2004). Abnormal Psychology (9th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Kapur, M. (1995). Mental Health of Indian Children. Sage Publications: New Delhi.

Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological Assessment. Oxford University Press: New York.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). Abnormal Psychology (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill: New York.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (2005). Abnormal Psychology. N.D.: Dorling Kindersley.

Sundberg, N. D., Winebarger, A. A., & Taplin, J. R. (2002). Clinical Psychology: Evolving Theory, Practice and Research. Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, N.J.

Taylor, S. (2006). Health Psychology. ND: Tata McGraw-Hill.

Wolman, B. B. (1975). Handbook of Clinical Psychology. New York: McGraw Hill.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 29). Cognitive Rehabilitation and 2 Important Approaches to It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/cognitive-rehabilitation/