Introduction

Obsessive-Compulsive and related disorders are a distinct category of psychiatric conditions characterized by intrusive thoughts, repetitive behaviors, and compulsions that cause significant distress and functional impairment. The DSM-5 (APA, 2013) recognizes these disorders as related due to shared features of repetitive behaviors and compulsivity, though their content and manifestation vary widely. This article provides a comprehensive overview of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), Hoarding Disorder, and Trichotillomania (Hair-Pulling Disorder), exploring classification, etiology, and treatment approaches.

Read More: DSM vs ICD

1. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

OCD is defined by the presence of obsessions, compulsions, or both that are time-consuming (more than one hour daily) or cause significant distress (APA, 2013).

- Obsessions: Persistent, intrusive, unwanted thoughts, urges, or images. Common themes include contamination, harm, symmetry, or forbidden thoughts.

- Compulsions: Repetitive behaviors or mental acts performed to reduce distress caused by obsessions. Examples include excessive washing, checking, counting, or repeating actions.

Example: A person may repeatedly wash their hands due to fear of contamination, despite knowing their fear is irrational.

Epidemiology

OCD affects 1–2% of the population, often beginning in late adolescence or early adulthood. Lifetime prevalence is slightly higher in women, and onset is often gradual (Barlow & Durand, 2005). Comorbid conditions include depression, anxiety disorders, and tic disorders.

Etiology

OCD is multifactorial:

- Genetic factors: Family and twin studies indicate moderate heritability (Nevid, Rathus, & Greene, 2014).

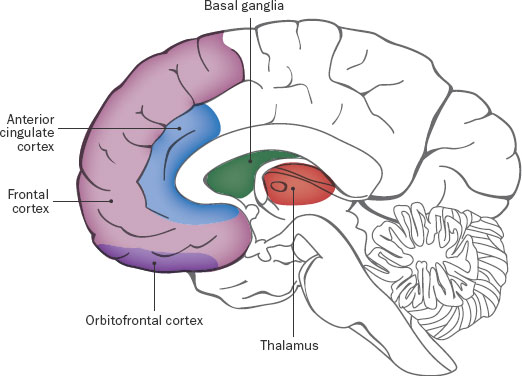

- Neurobiological factors: Dysfunction in cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuits and serotonin dysregulation are implicated (Butcher et al., 2014).

- Cognitive-behavioral model: Intrusive thoughts are misinterpreted as significant or dangerous, leading to compulsive behaviors to reduce distress (Andrew, 2011).

- Environmental factors: Childhood trauma, infections (PANDAS), and stressors can precipitate or exacerbate symptoms (Alloy, Riskind, & Manos, 2005).

Neurobiological Factors Causing OCD

Treatment

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) is the gold standard, exposing patients to feared stimuli while preventing compulsive responses.

- Pharmacotherapy: SSRIs (e.g., fluoxetine, sertraline) at high doses are first-line; augmentation with antipsychotics may help treatment-resistant cases (Carson et al., 2007).

- Combination therapy: CBT combined with pharmacotherapy often yields the best outcomes.

2. Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)

BDD involves preoccupation with perceived defects or flaws in physical appearance that are not observable or appear minor to others. Key criteria include:

- Persistent thoughts about physical appearance.

- Repetitive behaviors such as mirror checking, skin picking, or seeking reassurance.

- Clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or academic functioning (APA, 2013).

Example: An individual might spend hours checking a small skin blemish or seek cosmetic surgery repeatedly to correct perceived imperfections.

BDD Cycle

Epidemiology

BDD affects 1.7–2.4% of the general population. Onset typically occurs during adolescence, and it often co-occurs with OCD, depression, and social anxiety disorder (Butcher et al., 2014). Suicide risk is elevated due to severe distress and body dissatisfaction.

Etiology

- Biological factors: Serotonin dysregulation may contribute to obsessive preoccupations.

- Cognitive distortions: Overvaluation of appearance and selective attention to perceived flaws (Nevid et al., 2014).

- Environmental factors: Cultural and media influences, childhood teasing, or abuse may increase risk (Andrew, 2011).

- Personality traits: Perfectionism and high self-criticism are often observed.

Treatment

- CBT: Focus on cognitive restructuring, exposure to feared situations, and response prevention for appearance-related rituals.

- Pharmacotherapy: SSRIs are effective in reducing obsessive preoccupations and compulsive behaviors (Comer, 2007).

- Supportive therapy: Group therapy can reduce social isolation and enhance coping strategies.

3. Hoarding Disorder

Hoarding Disorder involves persistent difficulty discarding possessions, regardless of actual value, leading to clutter that disrupts living spaces and causes distress. Key features include:

- Excessive accumulation of items.

- Difficulty discarding possessions due to perceived need or emotional attachment.

- Impairment in daily functioning and safety risks (APA, 2013).

Example: An individual may fill multiple rooms with newspapers, mail, or household items to the point that normal living becomes impossible.

Epidemiology

Hoarding affects 2–6% of the population, often starting in early adolescence but worsening over decades. Comorbidity includes OCD, depression, and anxiety disorders (Butcher et al., 2014). Hoarding is associated with increased risk of fire, falls, and health hazards due to clutter.

Etiology

- Genetic factors: Twin studies suggest significant heritability (Nevid et al., 2014).

- Cognitive-behavioral factors: Dysfunctional beliefs about possessions (e.g., “I might need this later”) and difficulty organizing items.

- Emotional factors: High anxiety associated with discarding items, excessive attachment, and fear of waste.

- Environmental factors: Childhood neglect, trauma, or poverty may contribute (Alloy et al., 2005).

Treatment

- CBT for hoarding: Focuses on decision-making, organization skills, exposure to discarding items, and cognitive restructuring.

- Pharmacotherapy: SSRIs may be useful, particularly in comorbid OCD.

- Family involvement: Support from relatives can help reduce clutter and reinforce therapeutic progress (Barlow & Durand, 2005).

4. Trichotillomania (Hair-Pulling Disorder)

Trichotillomania is characterized by recurrent hair pulling, resulting in noticeable hair loss and significant distress. Diagnostic criteria include:

- Repeated attempts to reduce or stop hair pulling.

- Impairment in social, occupational, or academic functioning.

- Hair pulling may be triggered by stress, boredom, or sensory stimuli (APA, 2013).

Example: An individual may pull hair from the scalp, eyebrows, or eyelashes, often unconsciously, leading to visible bald patches.

Trichotillomania

Epidemiology

Trichotillomania affects approximately 1–2% of the population, with onset often in childhood or early adolescence. It is more prevalent in females and frequently co-occurs with anxiety disorders, OCD, and depression (Butcher et al., 2014).

Etiology

- Genetic factors: Familial aggregation suggests hereditary influence.

- Neurobiological factors: Dysfunction in corticostriatal circuits and abnormal habit learning mechanisms.

- Psychological factors: Hair pulling may serve as a coping mechanism to relieve tension, boredom, or negative affect (Carson et al., 2007).

- Environmental factors: Stress, trauma, or family dynamics may exacerbate symptoms.

Treatment

- Habit Reversal Training (HRT): Teaches alternative behaviors to replace hair pulling.

- CBT: Focuses on identifying triggers, emotional regulation, and preventing urges.

- Pharmacotherapy: SSRIs, N-acetylcysteine, or other medications may be considered for severe cases.

- Support groups: Peer support and psychoeducation can improve coping strategies.

Conclusion

Obsessive-Compulsive and related disorders—OCD, Body Dysmorphic Disorder, Hoarding Disorder, and Trichotillomania—represent a complex spectrum of psychiatric conditions unified by repetitive thoughts and behaviors. Etiology is multifactorial, involving genetic, neurobiological, cognitive, and environmental factors, and symptoms can cause profound distress and functional impairment. Evidence-based treatments, especially CBT, ERP, habit reversal, and SSRIs, are effective in managing symptoms and improving quality of life. Early identification, personalized interventions, and psychoeducation for patients and families are essential for optimal outcomes.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Andrew, M. (2011). Clinical psychology: Science, practice, and culture (2nd Edn). Sage Publication.

Alloy, L.B., Riskind, J.H., & Manos, M.J. (2005). Abnormal Psychology: Current perspectives (9th Edn). Tata McGraw-Hill.

Barlow, D.H., & Durand, V.M. (2005). Abnormal psychology (4th ed.). Pacific Grove: Books/Cole.

Butcher, J.N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J.M. (2014). Abnormal Psychology (15th Ed.). Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt. Ltd.

Carson, R.C., Butcher, J.N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J.M. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (13th Edn). Pearson Education, India.

Comer, R.J. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (6th ed.). New York: Worth Publishers.

Nevid, J.S., Rathus, S.A., & Greene, B. (2014). Abnormal Psychology (9th Edn). Pearson Education.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, September 29). Obsessive-Compulsive and 5 Important Related Disorders: Classification, Etiology, and Treatment. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/obsessive-compulsive-and-related-disorders/