Introduction

Mood disorders—principally depression and mania—constitute a major domain of psychopathology and clinical assessment. Accurate measurement of these conditions is essential for diagnosis, treatment planning, and evaluating therapeutic outcomes (Sarason & Sarason, 2005; Barlow & Durand, 1999).

Over the decades, various psychometric instruments have been developed to quantify the severity of depressive and manic symptoms. Two of the most empirically supported and widely applied tools are the Hamilton Depression Scale (HDRS or HAM-D) and the Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM).

Read More: Depression

Depression

Depression is characterized by persistent sadness, anhedonia, cognitive impairments, psychomotor changes, and physiological disturbances (Kaplan, Sadock, & Grebb, 1994). The DSM-5 classifies depressive disorders into major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, and others.

Biological theories implicate neurotransmitter imbalances (e.g., serotonin, norepinephrine), while cognitive models (Beck, 1967; Alloy, Riskind, & Manos, 2005) emphasize maladaptive thought patterns such as hopelessness and negative self-schema. Behavioral models, in turn, associate depression with reduced reinforcement and learned helplessness (Barlow & Durand, 1999).

Given its multifactorial etiology, depression assessment requires multi-method tools—self-report, clinician rating, and physiological indices.

Mania

Mania represents the polar opposite of depression, involving elevated or irritable mood, grandiosity, increased energy, decreased need for sleep, and pressured speech. It is a hallmark of bipolar disorders, particularly bipolar I and II.

Manic states are associated with impaired judgment, impulsivity, and risk-taking behavior, leading to significant psychosocial dysfunction (Carson et al., 2007). From a neuropsychological perspective, mania reflects dysregulation in prefrontal-limbic networks and dopamine-mediated reward systems (Lezak, 1995).

Effective assessment must therefore capture both severity and fluctuation of symptoms over time—central to bipolar disorder diagnosis and management.

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D or HDRS)

Developed by Max Hamilton in 1960, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) is one of the most widely used clinician-administered tools for assessing the severity of depression. Hamilton’s objective was not to diagnose depression per se but to quantify symptom severity among already diagnosed patients (Davison et al., 2004).

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)

Its enduring popularity stems from robust psychometric validation, widespread clinical acceptance, and adaptability across research and clinical settings (Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2014).

Structure and Content

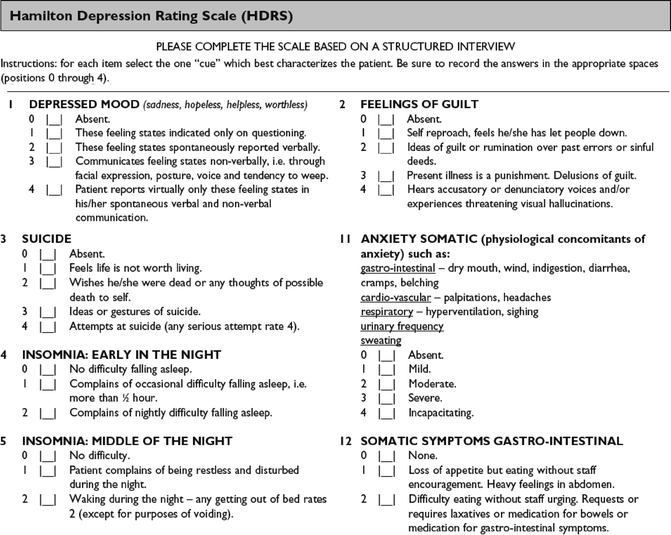

The most common version of HAM-D consists of 17 items, though extended versions with 21 or 24 items exist. Each item is rated on either a 3-point (0–2) or 5-point (0–4) Likert-type scale, depending on the symptom domain.

Score Distribution

Key symptom areas include:

- Depressed mood

- Guilt and self-reproach

- Suicide ideation

- Sleep disturbance

- Work and activity

- Psychomotor retardation or agitation

- Anxiety (psychic and somatic)

- Somatic symptoms (e.g., appetite, weight, libido)

Scores are summed to produce a total score ranging from 0–52. The conventional cutoffs are:

- 0–7: Normal or no depression

- 8–13: Mild depression

- 14–18: Moderate depression

- 19–22: Severe depression

- ≥23: Very severe depression (Carson et al., 2007)

Administration

The HAM-D is clinician-rated, requiring a structured or semi-structured interview. Administration takes approximately 15–20 minutes. Clinicians must clarify timeframes (typically “the past week”) and probe for both frequency and intensity of symptoms.

Training and inter-rater reliability are crucial to ensure consistency, as subjective interpretation of patient responses can influence scoring (Anastasi & Urbina, 2005).

Interpretation and Psychometric Properties

Scores reflect current depressive severity, enabling clinicians to monitor treatment progress.

- High scores on somatic items may indicate endogenous or melancholic depression.

- Elevated anxiety or agitation items suggest mixed depressive-anxious states.

- Decreased sleep and appetite ratings are associated with biological depression subtypes (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004).

Reliability: Inter-rater reliability typically ranges between 0.80–0.90.

Validity: Strong correlations with the Beck Depression Inventory (r = 0.70–0.90).

Sensitivity: Effective for detecting symptom changes during pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions (Sarason & Sarason, 2005).

Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM)

Developed by Edward Altman and colleagues in 1997, the ASRM was designed as a brief, self-administered measure of manic symptoms suitable for both clinical and research use (Carson et al., 2007).

Unlike clinician-rated tools such as the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), the ASRM allows individuals to self-assess their manic states quickly, enhancing efficiency and patient engagement. It aligns with DSM-5 manic symptom criteria, including elevated mood, decreased sleep need, and increased goal-directed activity.

Structure and Format

The ASRM consists of five items, each corresponding to a core manic domain:

- Elevated mood

- Increased self-confidence

- Decreased need for sleep

- Talkativeness (pressured speech)

- Excessive activity (motor or goal-directed)

Each item has five response options (0–4) representing severity. Total scores range from 0–20, with:

- 0–5: No mania

- 6–10: Mild

- 11–15: Moderate

- 16–20: Severe mania

Scores ≥6 generally indicate clinically significant mania or hypomania (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004).

Administration and Scoring

The ASRM can be completed in 2–3 minutes, either paper-based or electronically. It is ideal for repeated administration to monitor symptom fluctuations, particularly in outpatient and longitudinal settings (Taylor, 2006).

Because it is self-rated, the ASRM provides valuable patient-centered data, reflecting subjective experiences that may not be visible during clinical observation (Brannon & Feist, 2007).

Interpretation and Psychometric Qualities

Studies report high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ≈ 0.80–0.85) and strong correlation with clinician-rated mania scales such as YMRS (r = 0.70–0.85).

Interpretation involves:

- Identifying elevated total scores suggesting hypomanic or manic episodes.

- Comparing scores across sessions to monitor treatment response or relapse.

- Using results alongside depression scales (e.g., HAM-D) to detect mixed affective states (Carson et al., 2007).

Integration into Clinical Practice

A comprehensive mood assessment integrates:

- Objective measures (HAM-D, ASRM).

- Clinical interviews exploring history and triggers.

- Behavioral observations for psychomotor and affective cues.

- Collateral reports from family members or caregivers.

Such triangulation enhances diagnostic accuracy and fosters individualized treatment strategies—consistent with the biopsychosocial model emphasized in modern abnormal psychology (Sarason & Sarason, 2005; Sundberg, Winebarger, & Taplin, 2002).

Conclusion

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale are indispensable tools for assessing the two poles of mood disorders. The HAM-D offers a clinician-centered, detailed assessment of depressive severity, while the ASRM provides an efficient, patient-centered measure of manic symptoms.

Together, they enable clinicians to capture the full spectrum of affective dysregulation, supporting early intervention, treatment evaluation, and relapse prevention. As emphasized by Carson et al. (2007) and Sarason & Sarason (2005), the integration of standardized measurement with clinical judgment represents the hallmark of effective psychological assessment and evidence-based practice.

References

Alloy, L. B., Riskind, J. H., & Manos, M. J. (2005). Abnormal Psychology: Current Perspectives (9th ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill: New Delhi.

Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (2005). Psychological Testing (7th ed.). Pearson Education: India.

Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (1999). Abnormal Psychology (2nd ed.). Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole.

Brannon, L., & Feist, J. (2007). Introduction to Health Psychology. Thomson Wadsworth: Singapore.

Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2014). Abnormal Psychology (15th ed.). Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt. Ltd: Pearson Education.

Carson, R. C., Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (13th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Davison, G. C., Neal, J. M., & Kring, A. M. (2004). Abnormal Psychology (9th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Kaplan, H. I., Sadock, B. J., & Grebb, J. A. (1994). Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry (7th ed.). B. I. Waverly Pvt. Ltd: New Delhi.

Kapur, M. (1995). Mental Health of Indian Children. Sage Publications: New Delhi.

Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological Assessment. Oxford University Press: New York.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). Abnormal Psychology (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill: New York, USA.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (2005). Abnormal Psychology. Dorling Kindersley: New Delhi.

Sundberg, N. D., Winebarger, A. A., & Taplin, J. R. (2002). Clinical Psychology: Evolving Theory, Practice, and Research. Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, N.J.

Taylor, S. (2006). Health Psychology. Tata McGraw-Hill: New Delhi.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 15). 2 Important Depression and Mania Measures: Hamilton Depression Scale and Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/hamilton-depression-scale-and-altman-self-rating-mania-scale/