Introduction

In clinical psychology and psychiatry, the accurate classification, diagnosis, and assessment of mental disorders are crucial for effective treatment, research, and communication among professionals. Diagnostic systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11) serve as the foundational frameworks for identifying psychological disorders. Complementing these diagnostic manuals are structured clinical tools like the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) and the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0), which operationalize diagnostic criteria and measure the impact of mental disorders on daily functioning.

Read More: DSM vs ICD

1. DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and serves as a standardized classification system for mental disorders. Since its first edition in 1952, the DSM has evolved from a primarily descriptive tool to a comprehensive system emphasizing empirically derived criteria and diagnostic reliability (Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2014). The DSM-5, released in 2013, represents a paradigm shift toward a dimensional and integrative understanding of psychopathology, incorporating advances in neuroscience, genetics, and developmental psychology (Kaplan, Sadock, & Grebb, 1994; Carson, Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2007).

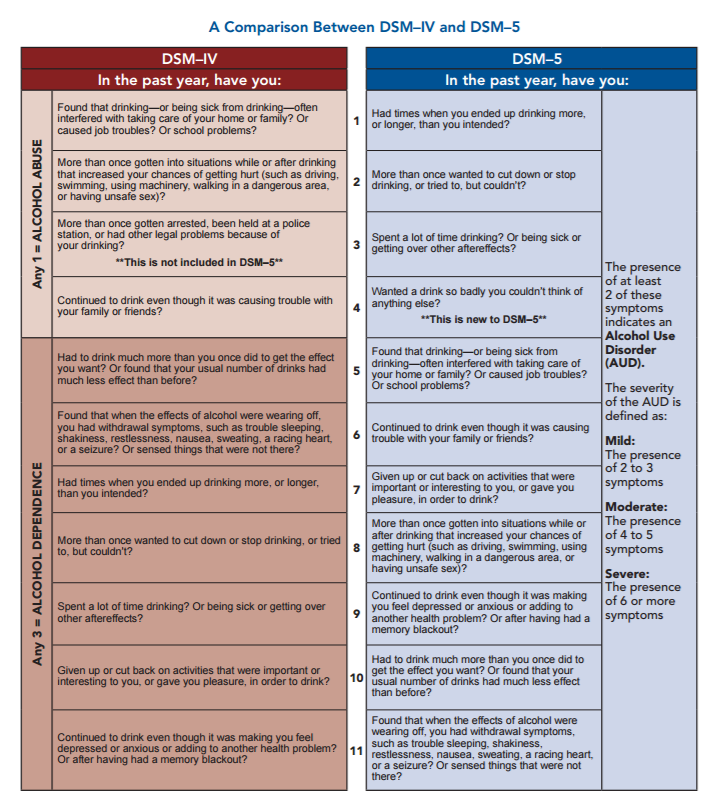

DSM-IV and DSM-5

Structure and Organization

DSM-5 organizes mental disorders into broad diagnostic categories based on symptom clusters and clinical features. The manual is divided into three main sections:

- Section I: Basics and use of the manual, outlining the purpose and structure.

- Section II: Diagnostic criteria and codes for all recognized mental disorders.

- Section III: Emerging measures, models, and conditions requiring further research.

The diagnostic criteria for each disorder are operationalized through specific symptom lists, duration requirements, and impairment indicators, ensuring diagnostic precision (Davison, Neal, & Kring, 2004).

Dimensional and Cross-Cultural Revisions

A notable advancement in DSM-5 is its inclusion of dimensional assessments that evaluate symptom severity, frequency, and duration. This approach addresses comorbidity and the heterogeneity of disorders, bridging the categorical-diagnostic gap (Barlow & Durand, 1999).

Furthermore, DSM-5 incorporates a Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI) to account for cultural influences on the expression and interpretation of mental disorders—reflecting global diversity in psychopathology (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004).

Criticisms and Limitations

Despite its scientific rigor, DSM-5 has faced criticism for potential over-pathologization of normal variations in behavior and emotion. Critics argue that some diagnostic categories lack sufficient empirical validation, while others have blurred boundaries (Sarason & Sarason, 2005). Additionally, the DSM’s reliance on symptom-based rather than etiological classification may limit its explanatory depth (Alloy, Riskind, & Manos, 2005).

2. ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision

The ICD-11, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), serves as the global standard for disease classification, including mental and behavioral disorders. Released in 2018, it aligns with international public health objectives, facilitating worldwide data collection, epidemiological research, and healthcare policy (Taylor, 2006).

Comparison with DSM-5

While the DSM-5 primarily serves psychiatric professionals, the ICD-11 covers all health conditions and is used globally across medical disciplines. Both manuals share conceptual similarities—reflecting efforts toward harmonization between the APA and WHO—but differ in scope and application.

For instance, ICD-11 integrates a more dimensional model of psychopathology, emphasizing the continuum between normality and disorder (Brannon & Feist, 2007). It also introduces user-friendly digital interfaces and culturally sensitive diagnostic guidelines, making it more adaptable for low- and middle-income countries (Kapur, 1995).

ICD-11

Structure of ICD-11 Mental and Behavioral Disorders

ICD-11 classifies mental disorders under the code range 6A00–6E8Z, covering major categories such as:

- Schizophrenia and other primary psychotic disorders

- Mood disorders

- Anxiety and fear-related disorders

- Disorders specifically associated with stress

- Personality disorders

- Neurodevelopmental disorders

- Disorders due to substance use or addictive behaviors

Each diagnosis in ICD-11 includes descriptions, essential diagnostic features, and differential diagnosis considerations (Lezak, 1995).

Clinical Utility and Research Impact

ICD-11 emphasizes clinical utility—ensuring that diagnostic descriptions are concise, comprehensible, and applicable across settings. By integrating dimensional elements, ICD-11 supports better treatment planning and outcome evaluation (Wolman, 1975). The manual’s harmonization with DSM-5 also promotes consistency in global research on psychopathology (Sundberg, Winebarger, & Taplin, 2002).

3. SCID-5: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) is a semi-structured diagnostic interview designed to ensure reliable, valid, and standardized psychiatric diagnoses based on DSM-5 criteria (Anastasi & Urbina, 2005). Developed by the APA, it is widely used in both clinical practice and research for assessing mental disorders in adults.

SCID 5-RV

Versions and Applications

There are several versions of the SCID-5, tailored to different diagnostic purposes:

- SCID-5-CV (Clinician Version): For clinical assessment.

- SCID-5-RV (Research Version): For research and academic studies.

- SCID-5-CT (Clinical Trials Version): For evaluating treatment efficacy.

- SCID-5-PD (Personality Disorders): For assessing DSM-5 personality disorder criteria.

Each version maintains a standardized format but allows clinical flexibility in probing symptoms and clarifying responses (Carson et al., 2007).

Structure and Administration

The SCID-5 consists of structured modules corresponding to diagnostic categories such as mood, psychotic, anxiety, and substance-use disorders. Each module begins with screening questions, followed by in-depth symptom-specific probes if initial criteria are met (Davison et al., 2004). The clinician’s judgment, combined with structured questioning, ensures both reliability and clinical sensitivity (Sarason & Sarason, 2005).

Reliability and Validity

Empirical research has demonstrated strong interrater reliability and diagnostic validity for the SCID-5 when administered by trained professionals. It minimizes diagnostic subjectivity and improves consistency across practitioners (Kellerman & Burry, 1981). Additionally, its modular format allows partial administration for targeted evaluations (Alloy et al., 2005).

Limitations

Despite its strengths, the SCID-5 can be time-consuming and requires significant clinical training. Misinterpretation of criteria or patient non-cooperation may compromise diagnostic accuracy (Kaplan et al., 1994). Nonetheless, it remains a gold standard for structured psychiatric assessment worldwide.

4. WHODAS 2.0: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0

The WHODAS 2.0 is a standardized instrument developed by WHO to assess health and disability across different cultures and conditions, including mental disorders. It operationalizes the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) model and is used alongside ICD and DSM systems to evaluate functional impairment (Taylor, 2006).

WHODAS-2.0

Domains and Structure

WHODAS 2.0 assesses functioning in six domains:

- Cognition – understanding and communicating

- Mobility – moving and getting around

- Self-care – hygiene, dressing, eating, and staying alone

- Getting along – interacting with others

- Life activities – domestic and work-related responsibilities

- Participation – joining in community and societal life

It is available in 12-item, 36-item, and interviewer-administered versions, making it adaptable to various contexts (Brannon & Feist, 2007).

Psychometric Strengths

WHODAS 2.0 has demonstrated robust psychometric properties across diverse populations. It correlates significantly with clinician-rated measures of disability, providing a reliable indicator of functional impairment (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). The instrument is cross-culturally validated and available in multiple languages, aligning with WHO’s mission of global mental health equity (Kapur, 1995).

Use in Clinical and Research Settings

Clinicians use WHODAS 2.0 to assess baseline functioning, monitor treatment outcomes, and plan rehabilitation. In research, it helps quantify the disability burden of specific disorders, informing public health strategies (Lezak, 1995). The DSM-5 also endorses WHODAS 2.0 as its recommended measure of disability, replacing the older Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale (Butcher et al., 2014).

Integration of Diagnostic and Assessment Systems

The DSM-5 and ICD-11 function as diagnostic taxonomies, while tools like SCID-5 and WHODAS 2.0 translate diagnostic criteria into measurable, clinical data. Together, they form a cohesive framework for understanding mental disorders—linking symptom identification, diagnostic classification, and functional assessment (Sarason & Sarason, 2005).

For example:

- The DSM-5 provides symptom criteria for Major Depressive Disorder.

- The SCID-5 ensures those criteria are systematically assessed.

- The WHODAS 2.0 quantifies the degree of impairment in daily life.

- The ICD-11 provides the international classification and coding standard for reporting and epidemiological comparison.

Such integration enhances the objectivity, reliability, and cross-cultural applicability of psychiatric assessment and treatment planning (Wolman, 1975; Sundberg et al., 2002).

Conclusion

The DSM-5, ICD-11, SCID-5, and WHODAS 2.0 collectively represent the cornerstone of modern clinical and diagnostic psychology. Each serves a distinct yet complementary role—classification, structured diagnosis, and functional assessment—ensuring that mental disorders are identified and managed systematically.

While debates persist regarding categorical versus dimensional approaches and cultural biases, these systems have significantly advanced the field’s diagnostic precision and scientific integrity. Their combined use supports a biopsychosocial understanding of psychopathology, emphasizing not just the presence of symptoms, but their real-world impact on human functioning and well-being.

References

Alloy, L. B., Riskind, J. H., & Manos, M. J. (2005). Abnormal psychology: Current perspectives (9th ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill.

Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (2005). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (1999). Abnormal psychology (2nd ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Brannon, L., & Feist, J. (2007). Introduction to health psychology. Thomson Wadsworth.

Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2014). Abnormal psychology (15th ed.). Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt. Ltd. of Pearson Education.

Carson, R. C., Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2007). Abnormal psychology (13th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Davison, G. C., Neal, J. M., & Kring, A. M. (2004). Abnormal psychology (9th ed.). Wiley.

Kaplan, H. I., Sadock, B. J., & Grebb, J. A. (1994). Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences, clinical psychiatry (7th ed.). B. I. Waverly Pvt. Ltd.

Kapur, M. (1995). Mental health of Indian children. Sage Publications.

Kellerman, H., & Burry, A. (1981). Handbook of diagnostic testing: Personality analysis and report writing. Grune & Stratton.

Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford University Press.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). Abnormal psychology (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (2005). Abnormal psychology. Dorling Kindersley.

Sundberg, N. D., Winebarger, A. A., & Taplin, J. R. (2002). Clinical psychology: Evolving theory, practice, and research. Prentice Hall.

Taylor, S. (2006). Health psychology. Tata McGraw-Hill.

Wolman, B. B. (1975). Handbook of clinical psychology. McGraw Hill.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 8). Overview of 4 Important Diagnostic Systems: DSM-5, ICD-11, SCID-5, and WHODAS 2.0. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/overview-of-diagnostic-systems/