Defining Personal Goals

Personal goals.- The end state toward which a human or nonhuman animal is striving, the purpose of an activity or endeavor. It can be identified by observing that an organism ceases or changes its behavior upon attaining this state.

Austin and Vancouver (1996, p. 338) define goals as “internal representations of desired states, where states are broadly construed as outcomes, events or processes.” Graduating from college, meeting new friends, or losing weight would exemplify goals as outcomes. While planning a wedding or having the family over for Thanksgiving would be examples of goals as events.

Goals as processes might include activities that are enjoyable in their own right, like reading, nature walks, spending time with friends, or working over time to develop particular skills or interests. Such as woodworking, musical talents, or athletic abilities. However, desired states may range from fulfillment of biological needs. Such as hunger, to more complex and long-term desires involved in developing a successful career, to “ultimate concerns” with transcendent life meanings expressed through religious and spiritual pursuits.

A pleasurable or painful memory of a past event may create plans to repeat certain actions and outcomes. Goals are in the form of achievements, aspirations, and fulfilled and unfulfilled dreams. However, they are a significant part of an individual’s life story and personal identity.

Goals are part of a larger motivational framework in which human behavior energizes and directs toward the achievement of personally relevant outcomes. Moreover, the diverse array of motivational concepts within psychology includes needs, motives, values, traits, incentives, tasks, projects, concerns, desires, wishes, fantasies, and dreams.

Self-defined personal goals capture how a need shared by all humans is translated or expressed in a particular individual’s life. Personal goals help connect the general to the particular.

Measuring Personal Goals

Researchers differ in how they define and measure personal goals; however, all conceptions attempt to capture what people are trying to accomplish in their lives in terms of personally desirable outcomes. Goals have been described as personal concerns, personal projects, personal strivings, and life tasks.

In personal project research, participants are told, “We are interested in studying the kinds of activities and concerns that people have in their lives. We call these personal projects. All of us have a number of personal projects at any given time that we think about, plan for, carry out, and sometimes (though not always) complete”. For example, “completing my English essay” and “getting more outdoor exercise”.

Life tasks introduced to participants with the following instructions. “One way to think about goals is to think about ‘current life tasks.’ For example, imagine a retired person. The following three life tasks may emerge for the individual as he or she faces this difficult time-

- Being productive without a job

- Shaping a satisfying role with grown children and their families

- Enjoying leisure time and activities.

These specific tasks constitute important goals since the individual’s energies directed toward solving them.

Goals grouped into categories to allow for comparisons among individuals. However, depending on the researchers’ interests and definition of the term “goal,” goal categories focuses on a particular life stage, circumstance, or time-span, or on more general goals that endure over time. Personal goals open up a rich assortment of interrelated factors for well-being researchers. Goals capture the guiding purposes in people’s lives that are central to happiness and satisfaction.

THE SEARCH FOR UNIVERSAL HUMAN MOTIVES

The issue of whether happiness has a universal meaning or varies widely across cultures is a much debated topic. This section examines the same issue focused on sources of goal-related motivations.

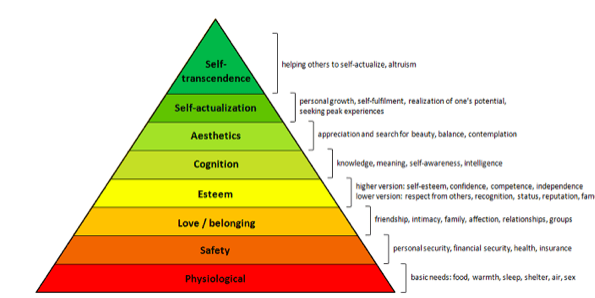

Abraham Maslow’s classic conception of a hierarchy of human needs (1943, 1954) was one of the earliest examples of a motivational hierarchy that attempted to specify universal sources of human motivation. Originally describing five needs, the model later expanded to eight needs regarded as universal among humans. Although the expansion occurred as the result of subdividing aspects of self-actualization into separate needs. Each need can be thought of as motivating a particular class of behaviors, the goal of which is need fulfillment.

Read More- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

- At the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy are basic physiological needs necessary for survival (e.g., needs for food and water).

- At the second level are needs for safety and security specifically needs for a safe, stable, and comforting environment in which to live, and a coherent understanding of the world.

- In like manner, belongingness needs, occupying the third rung of the hierarchy, include people’s desires for love, intimacy, and attachment to others through family, friendship, and community relationships.

- Esteem needs are fourth in the hierarchy. Also these include the need for positive self-regard and for approval, respect, and positive regard from others.

- Next in line are cognitive needs, including needs for knowledge, self-understanding, and novelty. Aesthetic needs seek fulfillment in an appreciation of beauty, nature, form, and order.

- Second to the top of the hierarchy are self-actualization needs for personal growth and fulfillment. Self-actualizing individuals fully express and realize their emotional and intellectual potentials to become healthy and fully functioning.

- Then, at the very top of the hierarchy is the need for transcendence, including religious and spiritual needs to find an overarching purpose for life.

8 Levels of Needs

Focus on Research- An Empirical Method for Assessing Universal Needs

Sheldon and his colleagues identified 10 needs that, based on their similarity, frequency of use, and empirical support within the motivational literature, might be universal.

- Self-esteem- The need to have a positive self-image, a sense of worth, and self-respect, rather than a low self-opinion or feeling that one is not as good as others.

- Relatedness- The need to feel intimate and mutually caring connections with others, and to have frequent interactions with others as opposed to feeling lonely and estranged.

- Autonomy- The need to feel that choices are freely made and reflect true interests and values. Expressing a “true self” rather than being forced to act because of external environmental or social pressures.

- Competence- The need to feel successful, capable, and masterful in meeting difficult challenges rather than feeling like a failure, or feeling ineffective or incompetent.

- Pleasure/stimulation- The need for novelty, change, and stimulating, enjoyable experiences rather than feeling bored or feeling that life is routine.

- Physical thriving- The need to be in good health and to have a sense of physical well-being rather than feeling unhealthy and out-of-shape.

- Self-actualization/meaning- The need for personal growth and development of potentials that define who one really is. Finding deeper purpose and meaning in life as opposed to feeling stagnant or feeling that life has little meaning.

- Security- The need to feel safe rather than threatened or uncertain in your present life circumstances; a sense of coherence, control, and predictability in life.

- Popularity/influence- The need to feel admired and respected by other people and to feel that your advice is useful and important, resulting in an ability to influence others’ beliefs and behaviors.

- Money/luxury- The need for enough money to buy what you want and to have nice possessions (as opposed to feeling poor and unable to own desirable material possessions).

Personal Goals Across Cultures

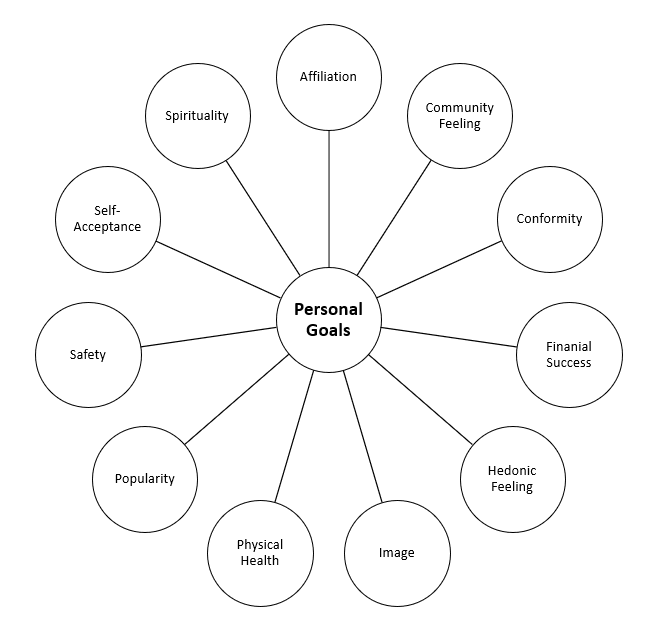

Attempts to delineate universal needs and values find a counterpart in a recent study of the content of human goals across 15 cultures. However this study provides evidence that the content and organization of personal goals and their connection to fundamental needs and values shared across cultures.

Multiple questionnaire items were used to assess each of the 11 goals. Further, participants rated each item according to its importance as a future life goal, on a scale of 1 (not at all important) to 9 (extremely important). Overall, the content of the 11 goals appears to be widely shared across cultures.

Goal measures showed acceptable levels of internal reliability and cross-culture equivalence. More importantly, analysis of participant ratings showed a consistent, coherent, and similar pattern for each of the 15 cultures. Based on the statistical pattern of responses, the content of personal goals showed a clear two-dimensional structure across different cultures.

11 Personal Goals

- Affiliation- Having satisfying relationships with family and friends.

- Community feeling- Making the world a better place through giving and activism.

- Conformity- Fitting in and being accepted by others.

- Financial success- Being financially successful.

- Hedonism- Having many sensually pleasurable experiences.

- Image- Having an appealing appearance that others find attractive.

- Physical health- Being physically healthy and free of sickness.

- Popularity- Being admired by others, well-known or famous.

- Safety- Able to live without threats to personal safety and security.

- Self-acceptance- Feeling competent, self-aware, self-directed and autonomous.

- Spirituality- Developing a spiritual/religious understanding of the world.

Intrinsic versus Extrinsic Goals

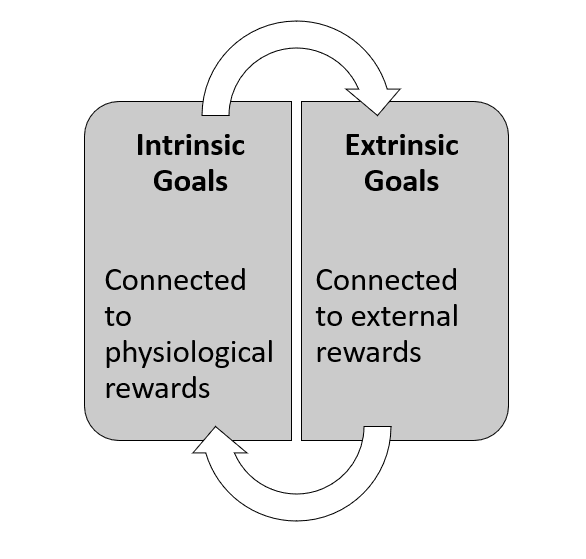

Intrinsic goals are defined by their connection to important psychological needs that are assumed to make their pursuit and fulfillment inherently satisfying. Of the 11 goals measured in this study, intrinsic goals included self acceptance, affiliation, community feeling, physical health, and safety.

Whereas, Extrinsic goals express desires for external rewards or praise and admiration from others and are assumed to be less inherently or deeply satisfying when pursued or attained. Extrinsic goals included financial success, image, popularity, and conformity. Goals on this dimension showed high internal consistency.

Intrinsic vs Extrinsic Goals

Physical versus Self-Transcendent Goals

Goals associated with the physical versus self-transcendence dimension showed less internal consistency and some overlap with intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Some pleasure/survival and self-transcendence goals may also have intrinsic and extrinsic components.

Physical goals defined by hedonism (seeking pleasure and avoiding pain) and needs for safety, security, and good health. Financial success, interpret as the means to achieve physical goals, also associates with this dimension.

Whereas, Self-transcendence goals encompassed needs for a spiritual/religious understanding of life, community feeling promoted by benefiting others and improving the world, and conformity needs reflecting desires to fulfill social obligations and be accepted by others.

Materialism And Its Discontents

Freud described the frustrations, sufferings, and dilemmas that result from the inevitable conflict between the self-centered needs of individuals and the co-operative and self-sacrificing requirements of civilized society. Whereas, studies of materialism seem to describe a similar dilemma between what Ryan referred to as the “religions of consumerism and materialism” in affluent societies and the unhappiness that befalls their faithful followers.

Materialism and consumption can be blamed for any number of macro-level social and environmental ills. From the great divide between the “haves” and the “have-nots” to global warming and environmental degradation. However, psychological studies offer a more micro-level view of the individual consequences of materialistic life aspirations.

Kasser and Ryan (1993) examined the relationship between college students’ life priorities and measures of well-being. However, the relative importance of four goals used to assess students’ central life aspirations. Assessment of Life aspirations in two ways: a measure of guiding principles and an aspiration index.

The guiding principles measure asked students to rank-order the importance of five values: money, family security, global welfare, spirituality, and hedonic enjoyment. Whereas, the life aspirations index involved rating the importance and likelihood of attaining four goals.

In three separate studies involving nearly 500 young adults. Kasser and Ryan (1996) found a consistent inverse relationship between financial aspirations and well-being. In other words, placing high priority on financial success was related to lower well-being.

Reference

Positive Psychology. Baumgardner and Crothers. 2015. Pearson India Education.

Positive Psychology: The Science of Happiness and Flourishing.

Subscribe to Careershodh

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 18,526 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2022, May 5). What are Personal Goals and 10 Important Universal Human Needs. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/what-are-personal-goals/