Introduction

Stress disorders in childhood represent significant disruptions in emotional regulation, social functioning, and attachment behaviors. Among these, Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED) are particularly prominent in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). These disorders emerge primarily due to early adverse experiences, including neglect, abuse, or inconsistent caregiving. Understanding their diagnostic criteria, etiology, and treatment approaches is critical for effective clinical management.

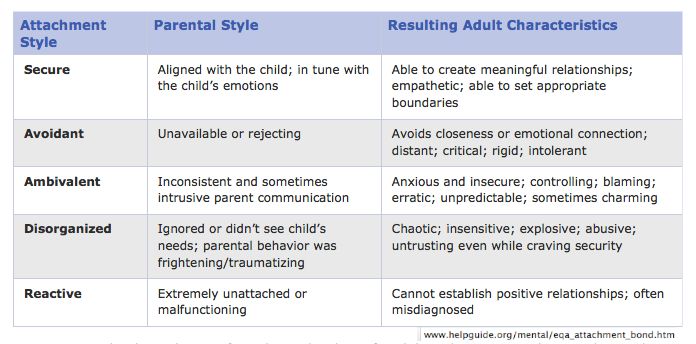

Attachment Styles

Read More: DSM vs ICD

Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD)

Reactive Attachment Disorder is a rare but serious condition in which a child fails to form normal emotional attachments with caregivers during early development. It usually manifests before the age of five and is associated with social withdrawal, emotional inhibition, and difficulty managing distress (APA, 2013; Barlow & Durand, 2005). Children with RAD exhibit minimal responsiveness to comfort and may appear emotionally detached, even in familiar environments.

Age-specific Annual Incidence of Reactive Attachment Disorder

Diagnostic Criteria

According to the DSM-5, RAD is diagnosed when the following criteria are met:

- A consistent pattern of inhibited, emotionally withdrawn behavior toward adult caregivers: The child rarely seeks or responds to comfort when distressed.

- Persistent social and emotional disturbance: Manifested by at least two of the following:

- Minimal social and emotional responsiveness.

- Limited positive affect.

- Episodes of unexplained irritability, sadness, or fearfulness in non-threatening interactions.

- History of insufficient care: Evidence of neglect, repeated changes in caregivers, or rearing in unusual settings such as institutions.

- Onset before age 5: Symptoms must appear in early childhood.

- Not attributable to autism spectrum disorder: Symptoms cannot be better explained by another developmental disorder (APA, 2013; Andrew, 2011).

Etiology

The development of RAD is closely linked to early disruptions in caregiving (Alloy, Riskind, & Manos, 2005). Key etiological factors include:

- Severe neglect or deprivation: Infants deprived of consistent emotional care often fail to form secure attachments.

- Repeated changes in caregivers: Multiple foster placements or institutional care can prevent attachment formation.

- Abuse or trauma: Physical, emotional, or sexual abuse contributes to attachment difficulties.

- Biological vulnerability: Some research suggests genetic and temperamental factors may influence susceptibility (Carson et al., 2007; Nevid, Rathus, & Greene, 2014).

The lack of reliable emotional caregiving during critical developmental periods leads to persistent disturbances in affect regulation and social engagement.

Clinical Features

Children with RAD exhibit:

- Emotional withdrawal and minimal responsiveness.

- Difficulty forming relationships with peers and adults.

- Failure to seek comfort when distressed.

- Hypervigilance or exaggerated fear responses.

- Limited social reciprocity and inability to express positive emotions (Barlow & Durand, 2005; Comer, 2007).

Treatment and Interventions

Effective intervention requires a multi-pronged approach, often combining psychosocial and therapeutic strategies:

- Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT): Focuses on enhancing caregiver responsiveness and improving attachment security.

- Attachment-Based Therapy: Facilitates the development of trust, emotional regulation, and social reciprocity.

- Psychoeducation for caregivers: Educating caregivers about attachment needs, emotional responsiveness, and consistency.

- Behavioral interventions: Encouraging adaptive social behaviors and reinforcing positive interactions.

- Environmental stabilization: Reducing caregiver changes and providing consistent nurturing environments is crucial (Sue, Sue, & Sue, 2006; Barlow & Durand, 2005).

Evidence suggests that early and consistent interventions can significantly improve outcomes, though chronic cases may require long-term support.

Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED)

Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder is characterized by overly familiar behavior with strangers and a lack of appropriate social boundaries (APA, 2013). Unlike RAD, which involves emotional withdrawal, DSED manifests as indiscriminate sociability and reduced inhibition in social interactions. It typically arises in children with a history of neglect or inconsistent caregiving, particularly in institutional settings.

Diagnostic Criteria

DSM-5 outlines the following criteria for DSED:

- A pattern of behavior in which a child actively approaches and interacts with unfamiliar adults.

- At least two of the following behaviors:

- Reduced or absent reticence in approaching strangers.

- Overly familiar verbal or physical behavior.

- Diminished checking back with adult caregivers in unfamiliar settings.

- Willingness to go off with unfamiliar adults.

- History of insufficient care: Includes neglect, repeated caregiver changes, or institutionalization.

- Developmental age of at least 9 months: Symptoms cannot be observed in infants younger than 9 months.

- Not attributable to autism spectrum disorder: Social disinhibition cannot be explained by another developmental disorder (APA, 2013; Alloy, Riskind, & Manos, 2005).

Etiology

DSED shares similar risk factors with RAD but differs in behavioral expression:

- Early institutionalization: Prolonged stays in orphanages or group homes reduce consistent caregiver interaction.

- Severe neglect: Lack of emotional nurturing contributes to indiscriminate social behavior.

- Attachment disruption: Absence of secure attachment models leads to over-familiarity with strangers (Andrew, 2011; Barlow & Durand, 2005).

Biological predispositions may interact with environmental factors, amplifying social disinhibition tendencies.

Clinical Features

Children with DSED commonly show:

- Overfamiliarity with unfamiliar adults.

- Failure to maintain appropriate social boundaries.

- Reduced attachment behaviors toward primary caregivers.

- Impulsive interactions and poor risk assessment (Carson et al., 2007; Comer, 2007).

Unlike RAD, DSED children are socially active but lack selective attachments.

Treatment and Interventions

Treatment approaches aim to establish secure attachment patterns and appropriate social boundaries:

- Attachment-Focused Therapy: Strengthens caregiver-child bonding and nurtures trust.

- Parent Training Programs: Teaches caregivers strategies to manage over-familiar behaviors.

- Environmental Consistency: Stable caregiving and reduced transitions prevent reinforcement of disinhibited behaviors.

- Behavioral Interventions: Social skills training to recognize personal boundaries.

- Trauma-Informed Care: Addresses underlying trauma and neglect, enhancing emotional regulation (Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2014; Nevid et al., 2014).

Early intervention is particularly effective; children placed in consistent, nurturing homes demonstrate significant improvements in social functioning.

Main Diagnostic Criteria for RAD and DSED in DSM-IV a and DSM-5 b

Conclusion

Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder represent profound disruptions in early childhood attachment and social development. Both are rooted in experiences of neglect, abuse, or inconsistent caregiving, but manifest in divergent behavioral patterns. Early recognition, diagnosis, and intervention are crucial for mitigating long-term effects. Evidence-based treatments, including attachment-focused therapy, parent training, and trauma-informed care, demonstrate efficacy in improving social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes. Understanding these disorders enables clinicians to provide targeted interventions that foster secure attachments, appropriate social behaviors, and overall emotional well-being in affected children.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Alloy, L. B., Riskind, J. H., & Manos, M. J. (2005). Abnormal psychology: Current perspectives (9th ed.). New Delhi, India: Tata McGraw-Hill.

Andrew, M. (2011). Clinical psychology: Science, practice, and culture (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (2005). Abnormal psychology (4th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Books/Cole.

Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2014). Abnormal psychology (15th ed.). Delhi: Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt. Ltd.

Carson, R. C., Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2007). Abnormal psychology (13th ed.). India: Pearson Education.

Comer, R. J. (2007). Abnormal psychology (6th ed.). New York: Worth Publishers.

Nevid, J. S., Rathus, S. A., & Greene, B. (2014). Abnormal psychology (9th ed.). Pearson Education.

Sue, D., Sue, D. W., & Sue, S. (2006). Abnormal behavior (8th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, September 30). 2 Important Stress Disorders: Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED). Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/stress-disorders/