Introduction

India’s Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (MHCA 2017) represents a landmark in the recognition and protection of the rights of individuals with mental illness. It aligns Indian mental health legislation with international human rights frameworks, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD, 2006). This article explores the salient features of the MHCA 2017, with particular attention to the rights of persons with mental illness (PMI), and situates them within broader psychiatric, psychological, and legal contexts.

Read More: Illness Anxiety Disorder

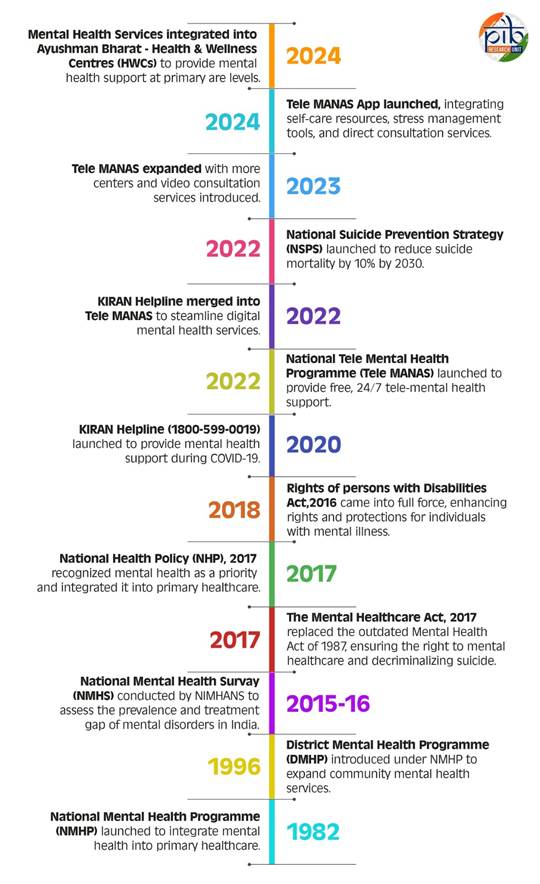

Historical Background

Earlier, India’s mental health laws—such as the Indian Lunacy Act, 1912 and the Mental Health Act, 1987—were custodial and paternalistic (Puri, Laking, & Treasaden, 1996). They emphasized institutionalization over community care and lacked strong rights-based frameworks (Andrew, 2011). The MHCA 2017 replaced the Mental Health Act, 1987, aiming to ensure dignity, autonomy, and access to treatment for all PMI.

National Mental Healthcare Policies

Objectives of MHCA 2017

The Act’s primary objectives are:

- To protect, promote, and fulfill the rights of PMI.

- To ensure mental health care services are affordable, accessible, and of good quality.

- To decriminalize suicide attempts and treat them as mental health concerns rather than crimes.

- To integrate mental health care with general health care systems.

Features of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017

Some of the important features of the MHCA 2017 include:

Mental Healthcare Act

- Rights-based framework: Unlike previous legislation, MHCA 2017 places rights at its core. PMI are recognized as equal citizens entitled to dignity, autonomy, and non-discrimination.

- Advance Directive: Individuals can specify their treatment preferences in advance, including consent or refusal of specific treatments (Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, Section 5).

- Nominated Representative: PMI can appoint a trusted person as a representative to make treatment decisions on their behalf (Section 14).

- Right to Access Mental Healthcare: Every person has the right to affordable, quality mental health services, including medications and hospitalization, funded partly by the government.

- Decriminalization of Suicide: Section 115 states that suicide attempts will no longer be treated as criminal offenses under IPC Section 309, recognizing that such attempts indicate severe distress.

- Mental Health Review Boards (MHRBs): Quasi-judicial bodies established to oversee treatment decisions, safeguard rights, and adjudicate complaints.

- Integration with General Healthcare: Mental health is no longer seen in isolation; hospitals must include psychiatric services.

- Special provisions for vulnerable groups: The Act mandates care for homeless persons, those in custodial institutions, and children with mental illness.

Rights of Persons with Mental Illness under MHCA 2017

The Act enumerates several enforceable rights:

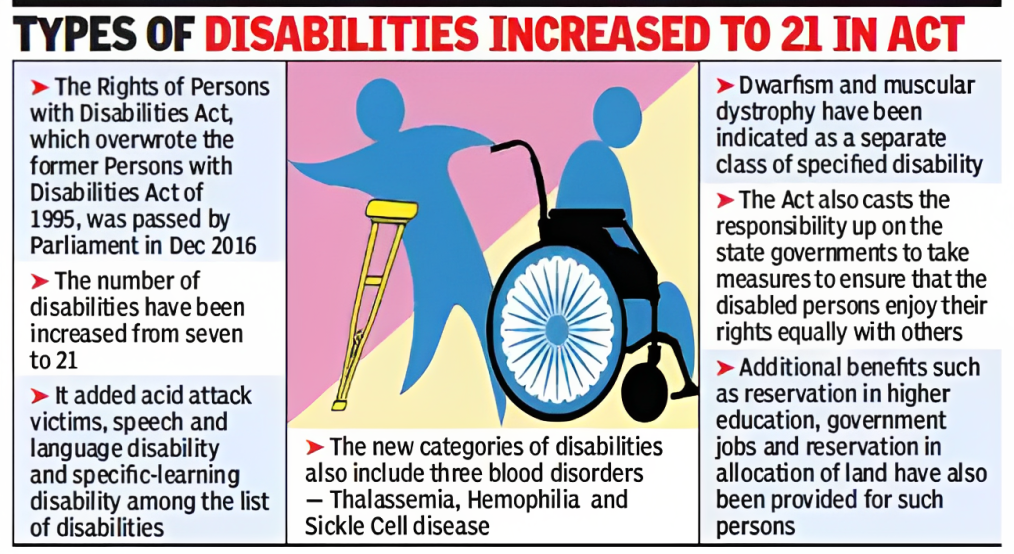

Types of Disabilities

- Right to Access Mental Healthcare (Section 18) – Free essential services and medicines for those below poverty line.

- Right to Community Living (Section 19) – Prohibition against being forced into institutions; emphasis on community-based care.

- Right to Protection from Cruel, Inhuman, and Degrading Treatment (Section 20) – Includes privacy, dignity, and humane living conditions in hospitals.

- Right to Equality and Non-discrimination (Section 21) – Protection from discrimination in housing, employment, education, and healthcare.

- Right to Information (Section 22) – Patients must be informed about diagnosis, treatment options, and rights.

- Right to Confidentiality (Section 23) – Protection of personal medical information.

- Right to Legal Aid (Section 27) – Free legal aid for PMI.

- Right to Make Complaints (Section 28) – Ability to approach Mental Health Review Boards.

Implementation Challenges

Despite its progressive nature, challenges remain:

- Resource gaps: India faces a shortage of mental health professionals (Butcher et al., 2014).

- Stigma: Deep-rooted stigma hinders help-seeking (Sarason & Sarason, 2002).

- Infrastructure: Limited psychiatric beds and uneven distribution of facilities (Comer, 2007).

- Awareness: Many PMI and families remain unaware of their rights.

- Funding: Adequate state and central government funding is critical for implementation (Davison et al., 2004).

Comparative Perspective

The MHCA 2017 aligns with global trends in rights-based mental health laws, similar to reforms in Europe and North America (Andrew, 2011; Oltmanns & Emery, 1995). However, unique features such as advance directives in a developing country context mark a progressive step forward.

Conclusion

The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 represents a paradigm shift in Indian mental health law. By foregrounding rights, autonomy, and dignity, it empowers persons with mental illness to live as full citizens. However, its success depends on effective implementation, resource allocation, and public awareness. For India, the MHCA 2017 is both a legal reform and a moral commitment to a humane and inclusive society.

References

Andrew, M. (2011). Clinical Psychology: Science, Practice, and Culture (2nd Ed.). Sage Publications.

Butcher, J.N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J.M. (2014). Abnormal Psychology (15th Ed.). Pearson Education.

Comer, R.J. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (6th Ed.). Worth Publishers.

Davison, G.C., Neal, J.M., & Kring, A.M. (2004). Abnormal Psychology (9th Ed.). Wiley.

Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (India).

Oltmanns, T.F., & Emery, R.E. (1995). Abnormal Psychology. Prentice Hall.

Puri, B.K., Laking, P.J., & Treasaden, I.H. (1996). Textbook of Psychiatry. Churchill Livingston.

Sarason, I.G., & Sarason, R.B. (2002). Abnormal Psychology: The Problem of Maladaptive Behavior (10th Ed.). Pearson Education.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, September 16). 8 Features of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 and Other Important Acts. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/mental-healthcare-act-2017/