Job Analysis

From a theoretical standpoint, job analysis is rooted in the principles of organizational psychology and human capital theory. It provides a structured method for identifying the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAOs) necessary for effective performance (Cascio & Aguinis, 2018). Thus, job analysis not only serves as a descriptive exercise but also as a predictive tool that informs how employees are selected, trained, and developed to achieve strategic objectives.

Job analysis is defined as the process of gathering, analyzing, and structuring information about a job’s components, characteristics, and requirements (Sanchez & Levine, 2000).

It is considered the cornerstone of human resource management (HRM) because virtually all HR functions—recruitment, selection, training, performance appraisal, and compensation—depend on a clear understanding of what a job entails. Without an accurate job analysis, organizations risk misalignment between employee capabilities and organizational demands (Aamodt, 2015).

Read More: Trends in Personnel Psychology

Importance of Job Analysis

The importance of job analysis can be explained on multiple levels. First, it provides the foundation for legal defensibility in employment practices. Courts have repeatedly ruled that employment decisions must be based on job-related information, as seen in Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971). Job analysis establishes the link between job requirements and personnel decisions, ensuring compliance with Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) standards (Cascio & Aguinis, 2018).

Second, job analysis is essential for performance management. By identifying specific duties and expected outcomes, it provides measurable criteria for performance appraisal, reducing reliance on vague or subjective traits such as “initiative” or “dependability” (Werner & Bolino, 1997). Clear performance benchmarks derived from job analysis improve fairness and accuracy in evaluation, consistent with organizational justice theory (Aamodt, 2015).

Third, it supports training and development by identifying competency gaps between existing employee skills and job requirements. Organizations can design targeted training programs that enhance productivity and align with business strategies (Cascio, 2010).

Finally, job analysis underpins compensation management by establishing internal equity. Through job evaluation methods, organizations can determine the relative worth of jobs and ensure fairness in pay structures (DeCenzo & Robbins, 2008). This is consistent with equity theory, which highlights the importance of fairness in reward distribution.

Writing a Good Job Description

A key outcome of job analysis is the job description, a formal document that summarizes the job’s purpose, responsibilities, working conditions, and requirements. According to Brannick, Levine, and Morgeson (2007), a comprehensive job description typically includes:

Writing Good Job Description

- Job Title – Provides clarity on the nature of the role and affects perceptions of job worth. Research shows that gender-neutral job titles (e.g., “administrative assistant”) are valued more highly than gender-linked titles such as “secretary” (Naughton, 1988).

- Job Summary – A concise statement describing the purpose and scope of the position.

- Work Activities – A detailed breakdown of the tasks performed, organized into functional categories for clarity.

- Tools and Equipment – A listing of the instruments, technology, and systems necessary to perform job duties.

- Job Context – Information about the physical and social work environment, stress levels, schedules, and degree of responsibility.

- Performance Standards – Criteria used to measure employee performance.

- Compensation Information – Classification and grade level of the job.

- Personal Requirements (Job Specification) – KSAOs required for successful performance.

A well-written job description not only clarifies employee expectations but also aids recruitment by attracting applicants whose skills match job requirements (Cascio & Aguinis, 2018).

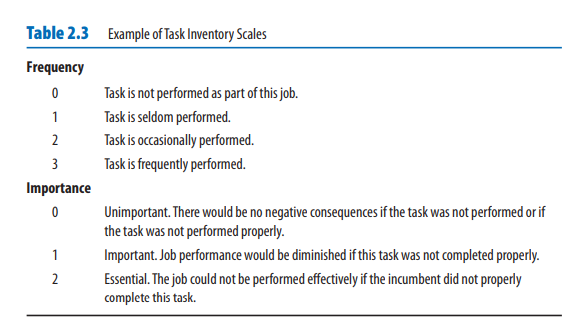

Task Inventory Scale

Preparing for a Job Analysis

Preparing for a job analysis involves several key considerations:

- Who Will Conduct the Analysis: Job analysis may be carried out by trained HR professionals, consultants, or supervisors. However, proper training in job analysis methodology is critical to ensure validity and reliability (Aamodt, 2015).

- Frequency of Updates: Jobs evolve over time, particularly in dynamic industries. Research shows that task stability drops significantly over a 10-year period, underscoring the need for regular updates (Vincent et al., 2007).

- Employee Participation: Choosing participants is crucial. Results may differ depending on whether high-performing or low-performing employees are consulted (Sanchez & Levine, 2000). Diversity in participant selection helps reduce bias stemming from gender, race, or experience (Landy & Vasey, 1991).

- Scope of Information: Analysts must decide the level of specificity required—whether to document detailed micro-tasks (e.g., keystroke-level actions) or broader job functions. The level of detail depends on the purpose of the analysis (Cascio, 2010).

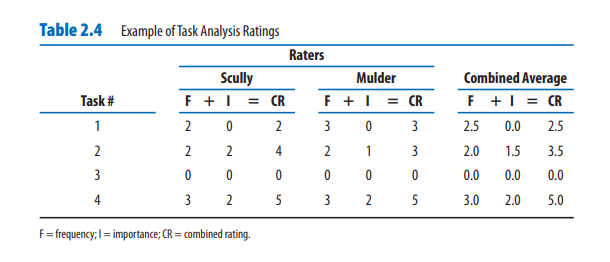

Task Analysis Rating

These preparatory steps ensure that the analysis is both methodologically sound and practically useful.

Conducting a Job Analysis

Job analysis is typically conducted through a step-by-step process:

- Identify Tasks Performed – Collect preliminary information from existing job descriptions, training manuals, or by interviewing subject matter experts (SMEs).

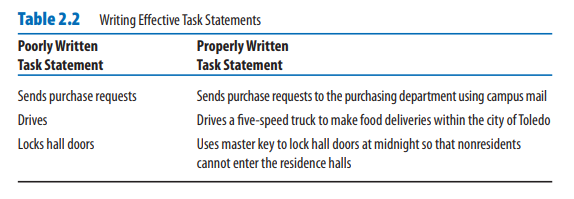

- Write Task Statements – Develop clear statements specifying the action, object, method, and purpose of each task (Degner, 1995).

- Rate Task Statements – SMEs rate tasks on frequency and importance, ensuring that training and appraisal focus on critical functions (Wilson & Harvey, 1990).

- Identify Essential KSAOs – Establish the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics required for effective performance. This may involve logical task-KSAO linkage or structured surveys such as the Fleishman Job Analysis Survey (F-JAS).

- Select Assessment Methods – Choose appropriate tools (e.g., structured interviews, tests, or assessment centers) to evaluate whether job applicants possess the identified KSAOs (Aamodt, 2015).

By following these steps, organizations ensure their HR practices are legally defensible and scientifically grounded.

Using Other Job Analysis Methods

Beyond interviews and observations, several structured methods have been developed:

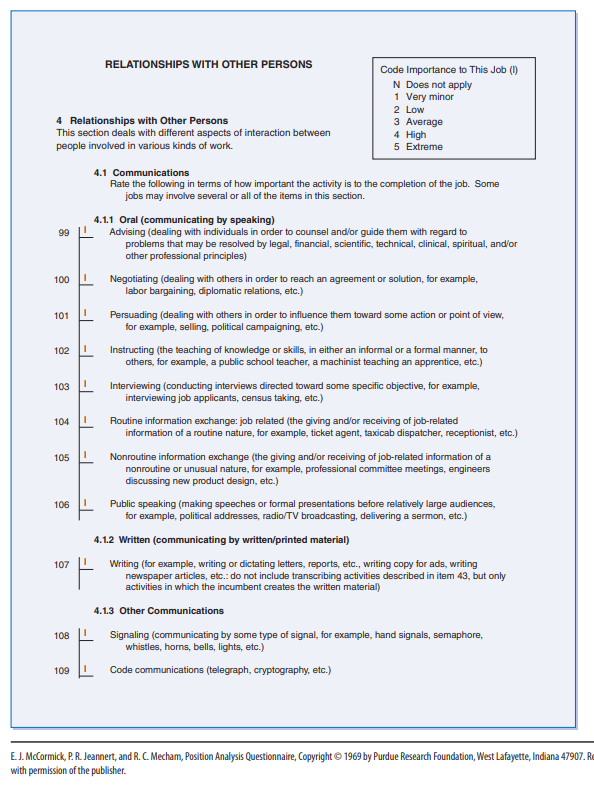

- Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ) – A standardized instrument with 194 items across six dimensions, including information input, mental processes, and relationships with others (McCormick, Jeanneret, & Mecham, 1972).

- Critical Incident Technique (CIT) – Focuses on identifying effective and ineffective work behaviors (Flanagan, 1954).

- Functional Job Analysis (FJA) – Classifies job tasks based on interaction with data, people, and things.

- Fleishman Job Analysis Survey (F-JAS) – Evaluates the worker abilities required across jobs.

- Personality-Related Position Requirements Form (PPRF) – Assesses personality-related competencies (Cascio & Aguinis, 2018).

Each method has unique advantages. Questionnaires provide efficiency and comparability, while interviews and observations capture context-specific details.

Example of PAQ Questions

Evaluation of Method

No single job analysis method is universally superior. Their utility depends on job complexity, organizational resources, and the purpose of analysis.

- Observation – Best for manual or repetitive jobs but less effective for cognitive or managerial work.

- Interviews – Provide rich qualitative insights but may suffer from respondent bias.

- Questionnaires (e.g., PAQ) – Offer efficiency and standardization but may oversimplify complex roles (Ash & Edgell, 1975).

- Work Diaries/Logs – Capture real-time detail but require significant employee effort.

- Hybrid Approaches – Combining multiple methods (e.g., interviews plus questionnaires) often produces the most reliable outcomes (Sanchez & Levine, 2000).

Ultimately, the evaluation of job analysis methods hinges on their validity, reliability, legal defensibility, and practical utility. When well executed, job analysis enhances productivity, improves role clarity, and ensures alignment between people and organizational strategy (Cascio, 2010).

References

Aamodt, M. G. (2015). Industrial/organizational psychology: An applied approach. Cengage Learning.

Ash, R. A., & Edgell, S. E. (1975). The PAQ and education: Problems and prospects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 229–232.

Brannick, M. T., Levine, E. L., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Job and work analysis: Methods, research, and applications for human resource management (2nd ed.). Sage.

Cascio, W. F. (2010). Managing human resources: Productivity, quality of work life, profits. McGraw-Hill Education.

Cascio, W. F., & Aguinis, H. (2018). Applied psychology in human resource management. Pearson.

DeCenzo, D. A., & Robbins, S. P. (2008). Personnel/human resource management. Prentice Hall of India.

Degner, J. (1995). Writing effective task statements. Personnel Psychology, 48(2), 341–356.

Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327–358.

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

Landy, F. J., & Vasey, J. (1991). Job analysis and race/gender bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(5), 531–540.

McCormick, E. J., Jeanneret, P. R., & Mecham, R. C. (1972). A study of job characteristics and job dimensions using the Position Analysis Questionnaire. Journal of Applied Psychology, 56(4), 347–368.

Naughton, T. J. (1988). The effects of job titles on job evaluation. Academy of Management Journal, 31(4), 933–944.

Sanchez, J. I., & Levine, E. L. (2000). Accuracy of job analysis information: The influence of sources and methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(6), 845–852.

Vincent, A., Rainey, L., Faulkner, M., Mascio, T., & Zinda, B. (2007). Stability of job descriptions across time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 809–820.

Werner, S., & Bolino, M. (1997). Explaining U.S. courts’ acceptance of job-related performance appraisals. Personnel Psychology, 50(1), 1–24.

Wilson, M. A., & Harvey, R. J. (1990). Validity of task inventories: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(6), 648–662.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 8). Job Analysis and 6 Important Methods to Do It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/job-analysis/