Introduction

The assessment of family conflict, environmental stressors, and caregiver burden represents an essential component of comprehensive psychological evaluation. Human functioning does not occur in isolation—psychological distress is often embedded within relational and contextual frameworks. As Sarason and Sarason (2005) emphasized, family and environmental dynamics substantially shape individual behavior, emotional regulation, and psychopathology. Therefore, understanding these systemic influences is vital for accurate diagnosis, case formulation, and intervention planning.

Family conflict and caregiver burden are multidimensional constructs influenced by communication patterns, role expectations, socioeconomic pressures, and cultural norms. Within the field of abnormal psychology, these constructs are evaluated through structured interviews, standardized scales, and observational techniques.

Read More: Family Therapy

Theoretical Framework

Three key theoretical frameworks include:

1. Systems Perspective

According to family systems theory, individuals are best understood within the network of relationships in which they exist (Carson, Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2007). Dysfunctional family interactions—such as enmeshment, triangulation, or rigid boundaries—can perpetuate maladaptive behaviors and psychological symptoms. The assessment of family conflict thus extends beyond individual pathology to the relational processes maintaining distress (Barlow & Durand, 1999).

2. Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial approach integrates biological vulnerability, psychological factors, and social context. Environmental stressors—such as poverty, unemployment, or community violence—may exacerbate family tension and caregiver strain (Taylor, 2006). Hence, clinical evaluation must incorporate environmental context to capture the full spectrum of influences on mental health.

3. Stress and Coping Theory

Sarason and Sarason (2005) identified family conflict as both a chronic stressor and a mediator of coping efficacy. When caregivers experience prolonged strain, their physical and psychological resources deplete, resulting in emotional exhaustion and health deterioration (Brannon & Feist, 2007).

Understanding Family Conflict

Family conflict refers to persistent patterns of disagreement, hostility, or lack of cohesion among family members. It may involve overt expressions (arguments, aggression) or covert dynamics (withdrawal, resentment). Chronic conflict impairs communication, emotional bonding, and problem-solving abilities (Davison, Neal, & Kring, 2004).

Psychological Impact

According to Nolen-Hoeksema (2004), exposure to high family conflict correlates with anxiety, depression, and behavioral issues, particularly in children. Adults in conflictual families often exhibit somatic complaints, irritability, and diminished coping resources. Lezak (1995) noted that stress within family systems may impair cognitive functioning, decision-making, and emotional regulation.

Contributing Factors

Key factors contributing to family conflict include:

- Personality Differences and Temperament Incompatibility

- Unrealistic Role Expectations (especially in caregiving relationships)

- Economic or Environmental Stressors

- Substance Abuse or Mental Illness within the family

- Poor Communication Patterns

- Cultural or Generational Value Clashes (Kapur, 1995)

These variables interact dynamically, creating a feedback loop of stress and maladaptive responses.

Assessment of Family Conflict

Family conflict assessment involves a multimethod, multi-informant approach designed to understand both explicit disagreements and implicit emotional patterns. Since conflict manifests differently across families—ranging from overt hostility to emotional disengagement—clinicians must integrate self-reports, behavioral observations, and contextual information (Sarason & Sarason, 2005; Kaplan, Sadock, & Grebb, 1994).

1. Clinical Interview

The clinical interview is often the first step in assessing family conflict. It provides qualitative insights into interactional patterns, emotional climate, and coping strategies.

Key elements include:

- Family Composition and Structure: Determining family roles, number of members, and household organization.

- History of Conflict: Exploring when disagreements began, common triggers, escalation patterns, and resolution attempts.

- Perceived Causes and Consequences: Understanding each member’s attributions regarding conflict (Carson, Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2007).

- Communication Patterns: Evaluating tone, respect, and listening behavior during conversations.

- Emotional Climate: Identifying pervasive emotions such as anger, guilt, fear, or detachment (Davison, Neal, & Kring, 2004).

Clinicians may conduct joint interviews (with multiple family members) or individual interviews, depending on the situation and safety concerns.

Barlow and Durand (1999) recommend maintaining neutrality and empathy to prevent defensive responses that may distort the data.

2. Observational Assessment

Observation—either in natural settings or structured family therapy sessions—helps the clinician identify nonverbal behaviors, dominance patterns, and alliance formations.

For example:

- Nonverbal Cues: Facial tension, eye contact avoidance, tone of voice.

- Interactional Sequences: Who initiates discussions, interrupts, or withdraws.

- Power and Control: Who exerts authority and who accommodates.

Structured observational methods include:

- Family Interaction Task (FIT): Families engage in problem-solving tasks while clinicians code behaviors.

- Marital Interaction Coding System (MICS): Assesses couple communication styles and emotional exchanges.

According to Sarason and Sarason (2005), observation provides ecological validity by capturing real-time relational dynamics often unreported in interviews.

3. Psychometric and Standardized Tools

Standardized assessment tools quantify family functioning and conflict levels objectively. Common instruments include:

- Family Environment Scale (FES): Developed by Moos and Moos; measures dimensions such as cohesion, expressiveness, and conflict. High scores on the conflict subscale indicate frequent tension and criticism (Carson et al., 2007).

- Family Assessment Device (FAD): Based on the McMaster Model, assessing problem-solving, roles, and affective involvement.

- Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS): Evaluates methods used to resolve disputes, distinguishing between negotiation, verbal aggression, and physical assault.

- Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales (FACES-IV): Assesses flexibility and emotional bonding within family systems (Anastasi & Urbina, 2005).

Clinicians should interpret results alongside cultural norms and family background (Kapur, 1995), as collectivist cultures may normalize dependency or hierarchy that might otherwise seem “rigid” in Western contexts.

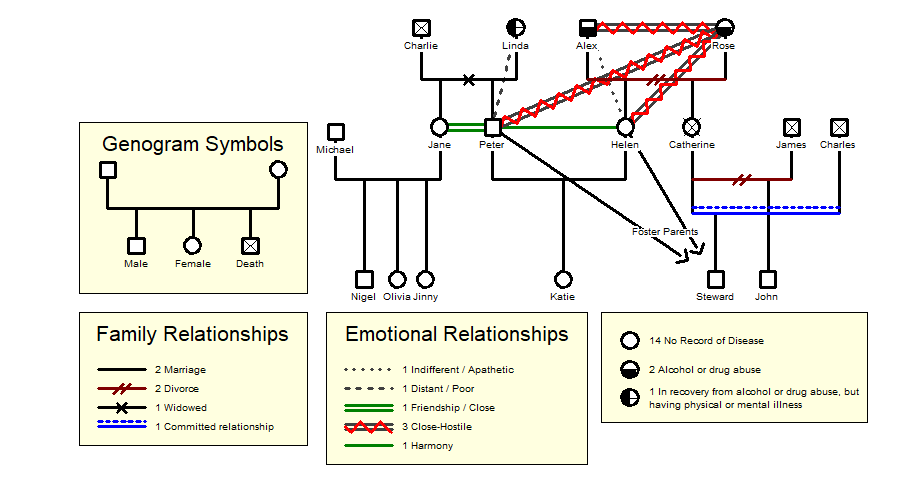

4. Genograms and Family Mapping

A genogram is a visual representation of a family across three or more generations, noting emotional ties, conflicts, mental illness, and substance use. It helps identify intergenerational transmission of relational patterns (Wolman, 1975).

Genogram

Symbols and color coding can highlight:

- Cross-generational alliances

- Emotional cutoffs

- Repetitive conflicts (e.g., parent–child hostility)

This method integrates both historical and emotional data, linking past experiences to current family functioning (Davison et al., 2004).

5. Self-Report Questionnaires

Self-report inventories allow family members to express perceptions of relationships anonymously, reducing social desirability bias. Examples include:

- Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) for marital satisfaction.

- Parent–Adolescent Communication Scale (PACS) for family communication patterns.

Discrepancies between self-reports of different members often indicate relational misperceptions and hidden resentments (Sarason & Sarason, 2005).

6. Cultural and Contextual Assessment

Family conflict cannot be detached from cultural, socioeconomic, and environmental realities.

Clinicians must explore:

- Cultural norms about authority, gender, and child-rearing (Kapur, 1995).

- Socioeconomic pressures, including unemployment or housing constraints (Taylor, 2006).

- Social supports such as extended family networks, community groups, and religious institutions.

These factors contextualize the meaning of conflict, distinguishing between normative family tension and maladaptive dysfunction.

Caregiver Burden

Caregiver burden refers to the physical, psychological, social, and financial strain experienced by individuals caring for someone with chronic illness, disability, or mental disorder. According to Taylor (2006), caregiver stress is multidimensional, encompassing both objective burden (time, tasks, financial cost) and subjective burden (emotional distress, guilt, fatigue).

Caregiver Burden

Psychological Sequelae

Research shows that high caregiver burden correlates with depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and decreased immune functioning (Brannon & Feist, 2007). Chronic stress may lead to burnout and compromised caregiving capacity.

Determinants of Caregiver Burden

- Severity and chronicity of the patient’s illness

- Lack of social or institutional support

- Role strain and lack of respite care

- Personal coping style and health status of caregiver (Sarason & Sarason, 2005)

Assessment of Caregiver Burden

Caregiver burden assessment is critical in families coping with chronic illness, disability, or mental disorder. According to Taylor (2006), caregiver stress can precipitate psychopathology, interpersonal conflict, and reduced caregiving quality. Thus, evaluating burden ensures both caregiver well-being and patient safety.

1. Clinical Interview and Narrative Approach

A biopsychosocial interview explores:

- Objective burden: Time spent caregiving, physical tasks, financial cost.

- Subjective burden: Emotional exhaustion, guilt, frustration, helplessness.

- Health consequences: Sleep disturbance, appetite loss, psychosomatic symptoms.

- Coping resources: Social support, leisure, respite availability.

- Meaning-making: How caregivers interpret their role and relationship with the care recipient (Sarason & Sarason, 2005).

A narrative approach allows caregivers to share their lived experiences, which often reveal latent stressors beyond measurable scales.

2. Standardized Assessment Tools

Key instruments include:

- Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI): Measures subjective burden through questions about strain, embarrassment, and guilt. Widely used in dementia care (Anastasi & Urbina, 2005).

- Caregiver Strain Index (CSI): 13-item tool assessing employment impact, financial strain, and sleep loss.

- Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA): Assesses caregiver self-esteem, disrupted schedule, financial concerns, and family support.

- Relative Stress Scale (RSS): Designed for caregivers of individuals with mental illness, assessing emotional strain and social isolation.

Scores help quantify the extent of burden, guide interventions, and monitor changes over time (Brannon & Feist, 2007).

3. Observational Methods

Clinicians observe caregiver–patient interactions to identify signs of emotional fatigue or burnout:

- Short temper, impatience, or avoidance behaviors.

- Overprotectiveness or controlling tendencies.

- Withdrawal from social interactions.

As Wolman (1975) suggested, behavioral observation adds depth to self-reported burden, especially when caregivers minimize distress due to guilt or cultural norms.

4. Multidimensional Contextual Analysis

Caregiver burden should be understood in relation to:

- Family Support: Distribution of caregiving roles among relatives.

- Cultural Expectations: Societal norms that valorize caregiving, particularly among women (Kapur, 1995).

- Social Systems: Availability of respite care, community programs, or government benefits.

- Patient Factors: Level of dependency, behavioral symptoms, and gratitude or hostility toward the caregiver.

This ecological assessment reveals how structural and cultural contexts amplify or buffer caregiver stress.

Conclusion

Assessment of family conflict, environment, and caregiver burden requires systematic, culturally attuned, and ethically grounded methodology. It combines interviews, observations, and standardized instruments to reveal patterns of distress and resilience. As Sarason and Sarason (2005) emphasized, evaluating interpersonal and contextual factors enriches clinical understanding, ensuring that psychological interventions target not only individual symptoms but also relational ecosystems that sustain or alleviate them.

References

Alloy, L. B., Riskind, J. H., & Manos, M. J. (2005). Abnormal psychology: Current perspectives (9th ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill.

Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (2005). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (1999). Abnormal psychology (2nd ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Brannon, L., & Feist, J. (2007). Introduction to health psychology. Thomson Wadsworth.

Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2014). Abnormal psychology (15th ed.). Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt. Ltd. of Pearson Education.

Carson, R. C., Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2007). Abnormal psychology (13th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Davison, G. C., Neal, J. M., & Kring, A. M. (2004). Abnormal psychology (9th ed.). Wiley.

Kaplan, H. I., Sadock, B. J., & Grebb, J. A. (1994). Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences, clinical psychiatry (7th ed.). B. I. Waverly Pvt. Ltd.

Kapur, M. (1995). Mental health of Indian children. Sage Publications.

Kellerman, H., & Burry, A. (1981). Handbook of diagnostic testing: Personality analysis and report writing. Grune & Stratton.

Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford University Press.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). Abnormal psychology (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (2005). Abnormal psychology. Dorling Kindersley.

Sundberg, N. D., Winebarger, A. A., & Taplin, J. R. (2002). Clinical psychology: Evolving theory, practice, and research. Prentice Hall.

Taylor, S. (2006). Health psychology. Tata McGraw-Hill.

Wolman, B. B. (1975). Handbook of clinical psychology. McGraw-Hill.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 13). 6 Important Family Conflict/Environment and 5 Caregiver Burden Assessments. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/family-conflict-and-caregiver-burden/