Introduction

Behavior therapy, one of the most influential movements in modern counseling and psychotherapy, emerged as a reaction against the speculative nature of psychoanalysis and the subjective tendencies of humanistic approaches.

It focuses on observable behavior rather than unconscious motives, asserting that maladaptive behaviors are learned through conditioning and can thus be modified using systematic techniques (Rimm & Masters, 1987). Rooted in principles of learning theory and supported by empirical research, behavior therapy emphasizes measurable outcomes, structured interventions, and the scientific study of behavior change (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Read More: Psychoanalysis

Historical Background and Development

The origins of behavior therapy can be traced to early 20th-century behaviorism, notably the work of Ivan Pavlov, John B. Watson, and B. F. Skinner. Pavlov’s (1927) studies on classical conditioning demonstrated how associations between stimuli could shape reflexive responses. Watson (1913) extended this to human behavior, asserting that psychology should study observable actions rather than internal states. Skinner (1953), through operant conditioning, proposed that behavior is shaped by its consequences—reinforcement or punishment—which either increase or decrease the likelihood of recurrence.

In the 1950s and 1960s, behavior therapy emerged as a formal psychotherapeutic movement distinct from both psychoanalysis and humanistic therapy (Corsini & Wedding, 1995). Influenced by Joseph Wolpe’s systematic desensitization and Hans Eysenck’s empirical rigor, behavior therapy was grounded in experimental psychology and the principles of learning.

CBT

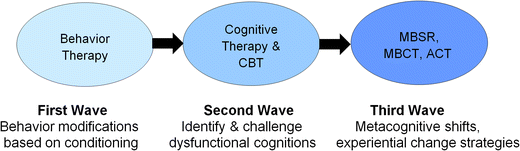

Over time, it evolved through successive “waves”: the first focused on direct behavior modification, the second integrated cognitive processes (e.g., Beck’s cognitive therapy and Ellis’s rational emotive behavior therapy), and the third wave incorporated mindfulness, acceptance, and relational frameworks (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

Core Assumptions of Behavior Therapy

Behavior therapy rests on several fundamental assumptions that differentiate it from other schools of psychotherapy.

1. Behavior is Learned and Can Be Unlearned

At its foundation, behavior therapy assumes that maladaptive behaviors are learned through conditioning processes and can be replaced by adaptive behaviors through re-learning (Rimm & Masters, 1987). This assumption shifts focus from unconscious drives or past experiences to current, observable actions.

2. Focus on the Present and the Observable

Unlike psychoanalysis, which explores the unconscious past, behavior therapy focuses on the present—on the specific behaviors that maintain a problem and the environmental contingencies that reinforce them (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

3. Empiricism and Scientific Method

Behavior therapy is grounded in the scientific method. Its interventions are operationally defined, empirically validated, and systematically evaluated. The therapist acts as a behavioral scientist, using assessment, hypothesis testing, and data collection to inform treatment (Feltham & Horton, 2006).

4. The Role of Learning Principles

All behavior, adaptive or maladaptive, is subject to the laws of learning—classical, operant, and social (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008). Consequently, treatment aims to alter learning contingencies to produce behavioral change.

5. Goal-Oriented and Time-Limited Treatment

Behavior therapy is typically goal-directed and structured, emphasizing short-term, measurable outcomes. Therapists and clients collaborate to identify target behaviors and set realistic behavioral objectives (Corey, 2008).

6. The Client as an Active Participant

Clients are active agents in the therapeutic process. They engage in behavioral experiments, homework assignments, and self-monitoring exercises designed to generalize new behaviors to daily life (Gelso & Fretz, 1995).

Major Forms of Behavior Therapy

Over the decades, behavior therapy has diversified into various forms, each grounded in distinct principles of learning and conditioning. The major forms include classical conditioning–based therapies, operant conditioning–based therapies, social learning approaches, and cognitive-behavioral integrations.

Behaviour Therapy

Classical Conditioning–Based Therapies

These approaches are based on Pavlovian principles where a neutral stimulus becomes associated with an unconditioned stimulus to elicit a conditioned response. Key techniques include:

- Systematic Desensitization: Developed by Joseph Wolpe (1958), systematic desensitization is used primarily for treating phobias and anxiety disorders. It involves gradual exposure to fear-provoking stimuli while maintaining a state of relaxation, thereby counterconditioning anxiety responses (Corey, 2008).

- Flooding and Exposure Therapy: Flooding involves direct exposure to the feared stimulus without gradual desensitization, allowing the anxiety to extinguish through habituation (Rimm & Masters, 1987). Modern exposure therapy, often used in trauma and obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment, applies controlled and graded exposure with response prevention.

- Aversion Therapy: Aversion therapy pairs a maladaptive behavior (e.g., substance use) with an unpleasant stimulus (e.g., nausea-inducing drug) to decrease the behavior’s occurrence (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008). Ethical concerns have led to its decline, though variations exist in treating addictive behaviors.

Operant Conditioning–Based Therapies

Based on Skinnerian principles, these methods modify behavior through reinforcement contingencies.

- Token Economies: Used in institutional settings, token economies reward desired behaviors with tokens exchangeable for privileges. They are effective in shaping socially adaptive behavior among children and psychiatric patients (Rimm & Masters, 1987).

- Contingency Management: Contingency management involves structuring the environment so that reinforcement and punishment systematically influence behavior. Therapists help clients identify triggers, consequences, and reinforcement schedules (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

- Behavior Modification Programs: These use operant principles to enhance self-management and habit control, such as in weight reduction or time management (Corey, 2008).

Social Learning and Observational Approaches

Albert Bandura expanded behavior therapy through social learning theory, emphasizing the role of modeling, imitation, and self-efficacy (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007). Techniques include:

- Modeling: Clients learn new behaviors by observing and imitating others, such as role models or the therapist.

- Self-Instructional Training: Clients develop internal dialogue to guide behavior and self-regulate impulses (Feltham & Horton, 2006).

- Assertiveness Training: Combines modeling and rehearsal to increase confidence and social competence (Gelso & Fretz, 1995).

Cognitive-Behavioral Approaches

The second wave of behavioral therapies integrated cognitive processes. The most influential models include:

- Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT): Developed by Albert Ellis (1975), REBT posits that irrational beliefs, not external events, cause emotional distress. Therapy involves identifying, disputing, and replacing irrational thoughts with rational alternatives.

- Cognitive Therapy (CT): Aaron Beck’s cognitive therapy (1976) focuses on identifying and modifying distorted cognitions that contribute to depression and anxiety. Behavioral experiments and thought records are used to challenge maladaptive beliefs.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT synthesizes cognitive and behavioral techniques into a structured model emphasizing skill acquisition, problem-solving, and relapse prevention (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008). It remains one of the most empirically validated forms of psychotherapy.

Third-Wave Behavior Therapies

The contemporary “third wave” integrates mindfulness, acceptance, and contextual factors into behavioral frameworks.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) emphasizes psychological flexibility and value-based living.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), developed by Marsha Linehan, integrates mindfulness with behavioral change strategies to treat borderline personality disorder.

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) incorporates meditation practices to prevent depressive relapse (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

These approaches highlight the evolving nature of behavior therapy as an adaptive, evidence-based discipline.

Applications of Behavior Therapy

Behavior therapy is used across diverse clinical and non-clinical contexts, including:

- Anxiety and Phobias: Exposure-based methods and relaxation training are highly effective (Rimm & Masters, 1987).

- Depression: Cognitive-behavioral approaches promote adaptive thinking and behavioral activation (Beck, 1976).

- Addictions: Contingency management and aversion therapy reduce substance dependence.

- Developmental and Behavioral Disorders: Token economies and parent-training models help manage ADHD and autism spectrum behaviors (Verma, 1990).

- Health Psychology: Behavior modification techniques address obesity, hypertension, and stress (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008).

Behavior therapy’s structured, measurable approach aligns well with contemporary evidence-based practice standards in psychology and counseling (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

The Role of the Therapist

In behavior therapy, the therapist functions as a coach, consultant, and teacher rather than a traditional “healer.” The relationship, while collaborative, is goal-oriented and instructional. The therapist models adaptive behavior, reinforces progress, and provides feedback based on observable data (Corey, 2008). Empathy and rapport remain essential, as client motivation and engagement directly influence treatment outcomes (Gelso & Fretz, 1995).

Criticisms and Limitations

Despite its empirical strength, behavior therapy has faced several criticisms. Critics argue that it may oversimplify complex human experiences by focusing narrowly on observable behavior (Feltham & Horton, 2006). Others contend that it neglects the emotional, relational, and existential dimensions of psychological distress.

However, the integration of cognitive, humanistic, and mindfulness elements has mitigated many of these limitations, leading to more holistic and flexible therapeutic models (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007; Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Conclusion

Behavior therapy represents one of the most enduring and empirically supported traditions in counseling psychology. Founded on scientific principles and refined through continuous evolution, it demonstrates how behavioral change can be systematically achieved through learning, reinforcement, and cognitive restructuring. From the early behaviorists to the cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based therapies of today, behavior therapy has transformed the landscape of mental health treatment.

Its enduring relevance lies in its adaptability—its ability to integrate empirical precision with humanistic understanding, addressing both the behavioral manifestations and cognitive underpinnings of psychological suffering (Gelso & Williams, 2022). Ultimately, behavior therapy continues to embody the spirit of modern counseling psychology: the pursuit of effective, evidence-based, and ethically grounded practice.

References

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and behavior disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

Capuzzi, D., & Gross, D. R. (2008). Counseling and psychotherapy: Theories and interventions (4th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Corey, G. (2008). Theory and practice of group counseling. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Corsini, R. J., & Wedding, D. (Eds.). (1995). Current psychotherapies. Itasca, IL: F. E. Peacock.

Ellis, A., & Harper, A. (1975). A new guide to rational living. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Feltham, C., & Horton, I. E. (Eds.). (2006). The Sage handbook of counselling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Gelso, C. J., & Fretz, B. R. (1995). Counselling psychology. Bangalore: Prism Books Pvt. Ltd.

Gelso, C. J., & Williams, E. N. (2022). Counseling psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2007). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Rimm, D. C., & Masters, J. C. (1987). Behavior therapy: Techniques and empirical findings. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Verma, L. (1990). The management of children with emotional and behavioral difficulties. London: Routledge.

Woolfe, R., & Dryden, W. (Eds.). (1996). Handbook of counseling psychology. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 12). Behavior Therapy and 6 Important Assumptions of It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/behavior-therapy/