Introduction

Among the most influential figures in modern psychotherapy, Aaron T. Beck revolutionized psychological treatment through the development of Cognitive Therapy (CT), which later evolved into Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT). His work transformed the field from a primarily interpretive and insight-oriented enterprise to one grounded in empirical observation, structured intervention, and measurable outcomes. Beck’s cognitive therapy redefined both the theory and practice of counselling and psychotherapy, emphasizing how cognitive processes shape emotional and behavioural functioning. This article explores the historical evolution, theoretical framework, therapeutic process, evidence base, and enduring impact of Beck’s cognitive therapy within the context of counselling psychology.

Read More: Psychodynamic Therapy

Historical Background

Beck’s cognitive therapy emerged in the 1960s as a reaction to the dominance of psychoanalysis and the rise of behavioural psychology. Trained in psychoanalytic theory, Beck sought to empirically validate Freud’s notion that depression resulted from repressed hostility turned inward. However, in his clinical research, he discovered that depressed patients primarily expressed streams of negative automatic thoughts—self-critical cognitions that distorted their perception of reality (Beck, 1976). This finding contradicted psychoanalytic assumptions and laid the foundation for his cognitive model of depression.

Beck published Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders in 1976, marking a turning point in psychotherapy. His emphasis on the testability of cognitive processes brought scientific legitimacy to the therapeutic enterprise (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008). Over time, cognitive therapy expanded beyond depression to encompass anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and various psychosomatic conditions. Its integration with behavioural methods in the 1980s and 1990s culminated in the broader framework now known as Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

Theoretical Foundations

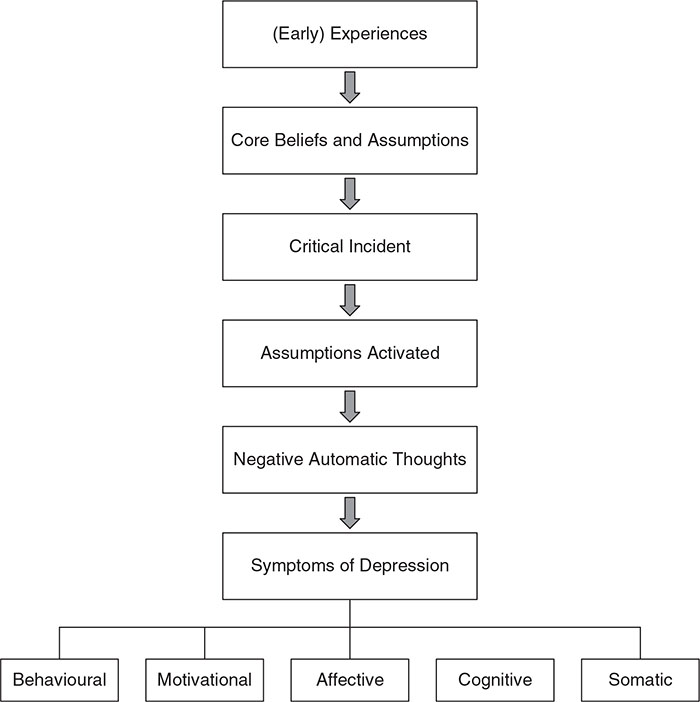

Beck’s cognitive therapy rests on a simple but profound premise: the way individuals think about events determines how they feel and act (Beck, 1976). In this model, emotional distress arises not from external events themselves but from distorted interpretations of those events. Cognitive therapy identifies three interacting levels of cognition:

- Automatic thoughts: Spontaneous, situation-specific thoughts that reflect an individual’s underlying beliefs. These are often negative, exaggerated, and accepted uncritically.

- Intermediate beliefs: Conditional assumptions and rules that guide perception and behaviour (e.g., “If I fail, I am worthless”).

- Core beliefs or schemas: Deeply held, often unconscious beliefs about the self, others, and the world, usually formed through early experiences (e.g., “I am unlovable,” “People cannot be trusted”).

Cognitive Models of Depression

These cognitive structures shape how individuals appraise situations, influencing emotional and behavioural reactions (Feltham & Horton, 2006). Beck conceptualised psychological disorders as the result of systematic cognitive distortions, such as all-or-nothing thinking, overgeneralisation, catastrophising, and emotional reasoning. Through therapy, clients learn to identify, evaluate, and modify these distortions to develop more adaptive ways of thinking.

The Cognitive Triad

One of Beck’s major contributions is the cognitive triad of depression, comprising negative views about the self (“I am worthless”), the world (“Everything is against me”), and the future (“Things will never improve”). These pessimistic beliefs interact recursively, maintaining the depressive cycle (Beck, 1976). The therapist’s task is to help the client recognise and challenge these cognitive biases, leading to cognitive and emotional restructuring.

Cognitive Triad

Collaborative Empiricism and Guided Discovery

Beck’s therapeutic stance is characterised by collaborative empiricism—the idea that therapist and client work together as co-investigators to examine evidence for and against maladaptive thoughts (Gelso & Williams, 2022). Rather than imposing interpretations, the therapist facilitates guided discovery, encouraging the client to reach conclusions through systematic questioning and experiential learning. This process fosters client autonomy, critical thinking, and self-efficacy, distinguishing Beck’s approach from more directive or interpretive models (Corey, 2008).

Structure and Process of Therapy

Beck’s cognitive therapy is structured, time-limited, and goal-oriented, typically spanning 12 to 20 sessions. The process unfolds in several stages:

- Assessment and formulation: The therapist gathers detailed information about the client’s presenting problems, identifies key automatic thoughts and beliefs, and develops a cognitive conceptualisation or case formulation (Gelso & Fretz, 1995).

- Socialisation to the cognitive model: The therapist educates the client about the relationship between thoughts, emotions, and behaviours, illustrating how cognitive distortions contribute to distress.

- Identification of automatic thoughts: Clients learn to monitor internal dialogues and record problematic thoughts in specific situations.

- Cognitive restructuring: The therapist and client evaluate the evidence supporting and refuting the identified thoughts and generate balanced, alternative cognitions.

- Behavioural experiments: Clients test new beliefs and behaviours in real-life situations to reinforce cognitive change.

- Relapse prevention: Toward the end of therapy, clients consolidate skills, develop self-therapy techniques, and prepare for future challenges.

Each session follows a consistent structure—agenda setting, review of homework, discussion of key issues, practice of cognitive and behavioural techniques, and assignment of new homework. This structure enhances focus, accountability, and efficiency (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008).

Key Techniques and Methods

Beck’s cognitive therapy employs a range of cognitive and behavioural techniques, including:

- Thought records: Clients document triggering events, automatic thoughts, emotions, and rational responses, thereby increasing metacognitive awareness.

- Socratic questioning: Therapists use guided questioning to help clients critically examine assumptions (e.g., “What evidence supports this thought?” “Are there alternative explanations?”).

- Decatastrophising: Clients learn to realistically evaluate feared outcomes and their ability to cope.

- Reattribution: Shifting from self-blame to balanced appraisals of responsibility.

- Behavioural activation: Encouraging engagement in pleasurable or goal-directed activities to counteract withdrawal.

- Activity scheduling: Structuring daily routines to improve motivation and functioning.

- Skills training: Teaching problem-solving, assertiveness, or relaxation techniques to support adaptive behaviour (Corey, 2008).

These interventions are empirically grounded, measurable, and adaptable across diverse client populations, aligning with the scientist–practitioner ethos of counselling psychology (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Strengths of Beck’s Cognitive Therapy

Beck’s model offers several distinctive strengths:

- Empirical foundation: Cognitive therapy pioneered the empirical evaluation of psychotherapy, setting a precedent for evidence-based practice (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008).

- Clarity and structure: The approach provides a systematic framework for conceptualisation, intervention, and outcome evaluation.

- Client empowerment: Through collaborative empiricism, clients become active participants in their own change process, enhancing autonomy and self-efficacy.

- Flexibility: Cognitive principles are adaptable across disorders, populations, and modalities, making CT and CBT the most widely practiced therapeutic orientations globally.

- Compatibility with counselling psychology: The model’s integration of scientific rigour, humanistic values, and skills training mirrors counselling psychology’s emphasis on combining science and practice (Gelso & Fretz, 1995).

Limitations and Critiques

Despite its strengths, Beck’s cognitive therapy is not without limitations. Critics have argued that it can appear overly intellectual or mechanistic, prioritising cognition over emotion and relationship (Feltham & Horton, 2006). The structured format may not suit clients seeking exploratory or existential depth. Moreover, its assumption of rational cognitive processing may not align with clients from cultures emphasizing collectivism, spirituality, or holistic worldviews (Veereshwar, 2002).

Additionally, some scholars contend that cognitive therapy’s focus on symptom reduction underplays the importance of underlying personality dynamics, social context, and systemic factors. In response, integrative and culturally adapted versions of CBT have been developed, blending cognitive restructuring with relational, emotional, and multicultural considerations (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Contemporary Developments

Since Beck’s original formulation, cognitive therapy has evolved considerably. Schema Therapy, developed by Young and colleagues, extends Beck’s ideas to long-standing personality and relational patterns by addressing deeper maladaptive schemas. Third-wave CBTs, such as Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), expand the focus from changing thoughts to altering the individual’s relationship with thoughts through mindfulness and acceptance (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

Furthermore, technology-assisted CBT—including online and app-based interventions—has expanded accessibility, particularly in underserved populations. Counselling psychologists increasingly incorporate these innovations while maintaining Beck’s foundational principles of collaborative empiricism, cognitive restructuring, and empirical accountability.

Relevance to Counselling Psychology

Beck’s cognitive therapy aligns closely with the core values of counselling psychology: empirical grounding, human development, prevention, and multicultural competence (Gelso & Williams, 2022). Counselling psychologists utilise cognitive conceptualisation to integrate clients’ thoughts, emotions, and behaviours within a holistic framework that considers social and cultural context. The model’s structured yet collaborative stance resonates with counselling psychology’s balance of scientific rigour and relational depth.

Training in Beck’s cognitive therapy equips practitioners with essential competencies—case formulation, guided discovery, and evidence-based intervention—while encouraging flexibility and responsiveness to individual client needs (Gelso & Fretz, 1995). The model’s emphasis on self-help and relapse prevention also supports counselling psychology’s goal of fostering autonomy and resilience rather than dependency.

Conclusion

Aaron Beck’s cognitive therapy represents one of the most significant revolutions in the history of psychotherapy. By grounding treatment in the systematic analysis of thought patterns and empirical verification, Beck transformed counselling and psychotherapy into a scientific, collaborative, and outcome-oriented discipline. His model not only provided a powerful framework for understanding and treating emotional disorders but also laid the foundation for subsequent innovations, including CBT and mindfulness-based approaches.

Within counselling psychology, Beck’s cognitive therapy continues to offer an integrative, evidence-based framework that balances empirical rigour with humanistic sensitivity. Though not without limitations, its principles of collaborative empiricism, cognitive restructuring, and skills-based empowerment remain central to effective counselling practice. Ultimately, Beck’s legacy endures in the countless practitioners and clients who, through awareness and modification of their thoughts, achieve greater emotional well-being and self-understanding.

References

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

Capuzzi, D., & Gross, D. R. (2008). Counseling and psychotherapy: Theories and interventions (4th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Corey, G. (2008). Theory and practice of group counseling. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Feltham, C., & Horton, I. E. (Eds.). (2006). The Sage handbook of counselling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Gelso, C. J., & Fretz, B. R. (1995). Counselling psychology. Bangalore: Prism Books Pvt. Ltd.

Gelso, C. J., & Williams, E. N. (2022). Counseling psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2007). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Veereshwar, P. (2002). Indian systems of psychotherapy. Delhi: Kalpaz Publications.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 14). Beck’s Cognitive Therapy and 6 Important Stages of It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/becks-cognitive-therapy/