Introduction

Transactional Analysis (TA) is a comprehensive theory of personality and a systematic psychotherapy approach developed by psychiatrist Eric Berne in the 1950s. It integrates elements of psychoanalytic, humanistic, and cognitive-behavioral thought to explain how individuals communicate, behave, and relate (Stewart, 2000; Feltham & Horton, 2006).

Eric Berne

TA proposes that human behavior can be understood through the analysis of transactions—the exchanges between individuals—and that maladaptive behavior results from dysfunctional patterns learned early in life. Within the counseling and psychotherapy landscape, TA offers both a theoretical framework for understanding interpersonal dynamics and a set of practical tools for facilitating personal growth and change (Gelso & Williams, 2022; Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

Read More: Approaches to Psychotherapy

Definition and Core Assumptions of Transactional Analysis

Berne’s foundational premise is that every person possesses three ego states—Parent, Adult, and Child—that shape thinking, feeling, and behavior. These ego states are not stages of development but consistent patterns of internal experience and expression. TA assumes that:

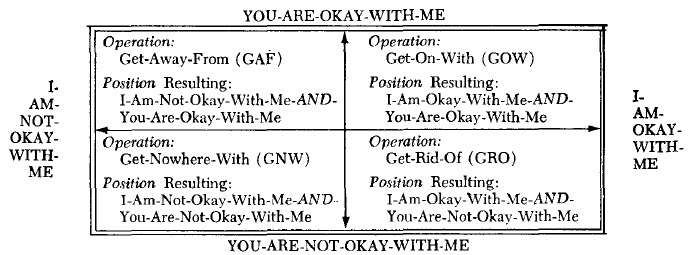

- People are fundamentally okay (the “I’m OK—You’re OK” philosophy).

- Everyone has the capacity to think and make decisions.

- Individuals can change self-defeating patterns through insight and redecision (Stewart, 2000).

In the therapeutic context, TA seeks to help clients recognize which ego states dominate their interactions, identify patterns of “games” or repetitive, self-defeating relational scripts, and develop autonomy through awareness, spontaneity, and intimacy (Feltham & Horton, 2006; Corey, 2008).

Historical and Theoretical Context

Berne’s early work was rooted in psychoanalysis, influenced by Freud’s structural model of id, ego, and superego. However, he diverged from classical analysis by emphasizing observable interpersonal communication rather than unconscious drives. TA evolved as a pragmatic, accessible model that demystified psychotherapy, using straightforward language and diagrams to explain complex dynamics (Stewart, 2000).

Following Berne’s death in 1970, subsequent theorists expanded TA into diverse schools: Classical TA (focusing on ego states and transactions), Cathexis TA (emphasizing redecision therapy), and Integrative TA (linking TA with psychodynamic and cognitive approaches) (Feltham & Horton, 2006). This evolution reflects the flexibility of TA as both a psychotherapeutic system and a social psychology of human relations (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

Structural Analysis

The cornerstone of TA theory is the structural model of personality comprising three ego states—Parent, Adult, and Child.

- Parent Ego State: Represents attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors learned from authority figures, often expressed as nurturing or critical.

- Adult Ego State: Represents objective, rational, here-and-now functioning, processing information based on current reality rather than past conditioning.

- Child Ego State: Contains feelings, creativity, and impulses developed during early childhood experiences; can manifest as free (spontaneous) or adapted (conforming or rebellious) (Stewart, 2000; Feltham & Horton, 2006).

Ego States

Therapeutic work involves helping clients identify when they are operating from each ego state, fostering awareness of habitual responses, and strengthening the Adult ego state to enable balanced, reality-based functioning (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Transactional Analysis

The term “transactional” refers to the exchanges between individuals, where each transaction is a stimulus–response interaction between ego states. There are three principal types of transactions:

- Complementary Transactions: Communication between compatible ego states (e.g., Adult–Adult) that maintain smooth interaction.

- Crossed Transactions: Communication between incongruent ego states that lead to misunderstandings or conflict (e.g., Adult–Child crossed by Parent–Child).

- Ulterior Transactions: Communications containing hidden messages, where social and psychological levels differ (e.g., flirtation, manipulation) (Stewart, 2000; Corey, 2008).

Transactions

Counselors use analysis of these transactions to clarify miscommunication patterns and teach clients to respond from the Adult state, enhancing effective communication and reducing emotional reactivity.

Games and Life Scripts

A central concept in TA is that people unconsciously engage in “games”—repetitive, covert patterns of interaction that result in negative feelings or “payoffs.” Games reinforce maladaptive beliefs formed in early life, such as “I am not okay” or “Others cannot be trusted” (Stewart, 2000). For example, the game “Why Don’t You – Yes But” reflects a dynamic where individuals seek help only to reject all solutions, reinforcing helplessness.

Life Scripts

Berne also proposed the idea of life scripts, internalized life plans developed in childhood based on parental messages and early decisions. These scripts guide life choices and relationships, often unconsciously. The goal of TA therapy is to help clients bring these scripts into awareness and rewrite them—achieving autonomy through redecision and self-acceptance (Feltham & Horton, 2006; Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

The Therapeutic Relationship in TA

TA emphasizes equality and collaboration in the therapeutic relationship. The therapist functions as an educator and facilitator, helping clients analyze communication patterns and identify life positions. Unlike traditional psychoanalysis, where the therapist is a distant authority, TA promotes open dialogue, contracts, and mutual respect (Stewart, 2000).

Gelso and Williams (2022) highlight that TA’s relational philosophy aligns with contemporary counseling psychology’s emphasis on collaboration, authenticity, and empowerment. The therapist encourages clients to shift from a “Child” position of dependency to an “Adult” stance of self-responsibility. This process is inherently humanistic, fostering growth through awareness and choice.

Therapeutic Goals and Techniques

The overarching goals of TA are awareness, spontaneity, and intimacy (Stewart, 2000). These outcomes represent the reclaiming of autonomy—the ability to think, feel, and act authentically rather than reactively. TA employs several structured techniques to achieve these goals:

- Contracting: The therapist and client agree explicitly on goals, methods, and responsibilities, reinforcing collaboration (Feltham & Horton, 2006).

- Ego-State Diagnosis: Through observation of verbal and nonverbal cues, the therapist helps clients identify active ego states and their impact on communication (Corey, 2008).

- Game Analysis: Exploration of recurring interaction patterns that yield negative outcomes, uncovering hidden motives or beliefs.

- Script Analysis: Examination of early decisions, parental injunctions, and life patterns, facilitating redecision.

- Reparenting and Redecision Techniques: Providing corrective experiences through nurturing interactions and reframing of childhood messages (Stewart, 2000; Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

These interventions align with cognitive-behavioral principles, focusing on self-awareness, decision-making, and behavioral change.

Integration with Other Approaches

TA’s flexibility allows integration with other therapeutic modalities. Capuzzi and Gross (2008) observe that TA shares common ground with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in its focus on identifying and modifying internal dialogues. Beck’s (1976) cognitive theory, emphasizing the restructuring of maladaptive thoughts, parallels TA’s concept of script redecision. Likewise, Ellis and Harper’s (1975) Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) shares TA’s emphasis on personal responsibility and rational self-evaluation.

TA also resonates with humanistic and existential therapies in its affirmation of personal worth and capacity for growth (Feltham & Horton, 2006). Woolfe and Dryden (1996) note that TA’s emphasis on authenticity, self-awareness, and relational patterns complements the counseling psychology tradition of integration and pluralism.

TA in Group and Educational Settings

Corey (2008) emphasizes that TA is particularly effective in group counseling and educational contexts. Group TA provides opportunities for participants to observe ego-state interactions in real time, receive feedback, and practice new communication styles. Group dynamics often mirror clients’ real-life relationships, making TA’s focus on games and transactions highly relevant. Similarly, TA has been applied in organizational development and education, promoting effective leadership, teamwork, and conflict resolution (Stewart, 2000).

Cultural and Contextual Adaptations

Like other Western-origin psychotherapies, TA must be applied with cultural sensitivity. Feltham and Horton (2006) caution that concepts such as autonomy and “I’m OK—You’re OK” may require reinterpretation in collectivist cultures where interdependence and hierarchy are valued. Eastern approaches to psychotherapy, as discussed by Veereshwar (2002) and Rama, Ballentine, and Ajaya (1976), emphasize harmony, mindfulness, and spiritual balance, offering complementary insights to TA’s rational and structural focus. Integration of these cultural perspectives can make TA more inclusive and contextually relevant (Watts, 1973).

Empirical Support and Effectiveness

Empirical studies and meta-analyses demonstrate TA’s effectiveness in improving self-esteem, communication, and interpersonal functioning (Stewart, 2000; Prochaska & Norcross, 2007). TA-based interventions have been used successfully with diverse populations, including children, couples, and organizational teams. Gelso and Williams (2022) note that TA’s clarity, structure, and emphasis on contracts make it particularly suitable for brief and goal-oriented therapy.

While early critics argued that TA lacked empirical rigor, more recent research has integrated quantitative assessment and outcome studies, affirming its relevance in contemporary psychotherapy (Feltham & Horton, 2006). TA’s accessible language also contributes to client engagement and empowerment, enhancing the therapeutic alliance—a key predictor of success across modalities (Gelso & Fretz, 1995).

Ethical Considerations

Ethical practice in TA, as in all counseling, emphasizes respect for client autonomy, informed consent, and professional boundaries (Feltham & Horton, 2006). The use of explicit contracts ensures transparency about therapeutic goals and responsibilities. However, the reparenting approach, which can involve nurturing interactions, demands careful ethical management to avoid boundary violations. Supervision and self-reflection are essential to ensure the therapist’s responses stem from professional intention rather than personal needs (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Critiques and Limitations

Despite its strengths, TA has faced criticism for oversimplifying complex psychological processes into rigid categories (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007). Some argue that the ego-state model risks stereotyping behavior, neglecting unconscious or cultural variables. Additionally, TA’s structured and didactic style may not suit clients seeking a more exploratory or emotion-focused process. Nevertheless, integrative and relational TA approaches have addressed these limitations by incorporating psychodynamic and humanistic insights (Stewart, 2000).

Conclusion

Transactional Analysis remains one of the most versatile and enduring models in counseling and psychotherapy. Its integration of psychoanalytic, cognitive, and humanistic concepts provides a clear framework for understanding communication and promoting personal change. By analyzing transactions, identifying life scripts, and cultivating awareness, clients can achieve autonomy and authenticity. As Gelso and Williams (2022) emphasize, TA exemplifies the broader counseling psychology tradition—grounded in respect for human potential, guided by scientific inquiry, and expressed through the therapeutic relationship. Through its balance of structure and empathy, TA continues to empower individuals to rewrite their life stories and engage more consciously with themselves and others.

References

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

Capuzzi, D., & Gross, D. R. (2008). Counseling and psychotherapy: Theories and interventions (4th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Corey, G. (2008). Theory and practice of group counseling. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Ellis, A., & Harper, A. (1975). A new guide to rational living. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Feltham, C., & Horton, I. E. (Eds.). (2006). The Sage handbook of counselling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.). London, England: Sage Publications.

Gelso, C. J., & Fretz, B. R. (1995). Counselling psychology. Bangalore, India: Prism Books Pvt. Ltd.

Gelso, C. J., & Williams, E. N. (2022). Counseling psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2007). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Rama, S., Ballentine, R., & Ajaya, S. (1976). Yoga and psychotherapy. Hinsdale, PA: Himalayan International Institute.

Stewart, I. (2000). Transactional analysis counseling in action. London, England: Sage Publications.

Veereshwar, P. (2002). Indian systems of psychotherapy. Delhi, India: Kalpaz Publications.

Watts, A. W. (1973). Psychotherapy: East and West. London, England: Penguin Books.

Woolfe, R., & Dryden, W. (Eds.). (1996). Handbook of counseling psychology. New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 7). Transactional Analysis and 5 Important Goals of It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/transactional-analysis/