Introduction

Reality Therapy, developed by William Glasser in the 1960s, is a widely applied counseling and psychotherapeutic approach grounded in Choice Theory. The central premise is that individuals are responsible for their behavioral choices and that psychological distress arises when people fail to meet their basic needs effectively (Glasser, as discussed in Corey, 2008). Reality Therapy, therefore, encourages clients to evaluate their present behavior, consider alternative choices, and take responsibility for change.

Read More: Psychodynamic

Reality Therapy

Historical and Theoretical Foundations

Glasser’s roots in psychiatry and educational reform heavily influenced Reality Therapy’s development. Dissatisfied with traditional medical-model interpretations of mental illness, Glasser argued that most psychological symptoms reflect personal choice, not pathology (Corsini & Wedding, 1995). The approach emerged as an alternative to psychoanalysis and behaviorism, prioritizing agency and responsibility over unconscious conflict or environmental conditioning.

Choice Theory as a Foundation

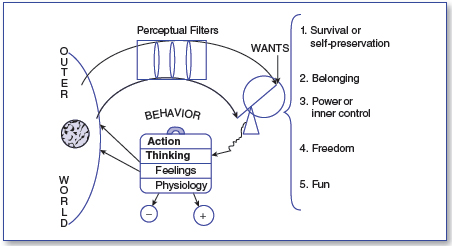

Choice Theory—initially called Control Theory—asserts that behavior is internally motivated by five genetically encoded psychological needs:

Survival

Love and belonging

Power/achievement

Freedom/independence

Fun/pleasure

Human problems occur when individuals attempt to meet these needs in ineffective or self-defeating ways (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008). Reality Therapy conceptualizes all behavior as “total behavior,” comprising acting, thinking, feeling, and physiology. Importantly, individuals have the most control over their actions and thoughts, which can indirectly influence emotions and bodily sensations (Corey, 2008).

Reality Therapy

View of Human Nature

Reality Therapy holds an optimistic view of human nature: people are capable of change, responsible for their choices, and able to learn more adaptive ways of fulfilling their needs. The approach rejects deterministic models of human functioning and emphasizes present behavior over past experiences (Gelso & Fretz, 1995). While personal history may shape current patterns, it does not excuse irresponsible choices.

According to Gelso and Williams (2022), this stance aligns with humanistic traditions within counseling psychology, which emphasize autonomy and self-directed growth. Reality Therapy’s positive, future-oriented emphasis resonates with broader movements in counseling that stress empowerment and personal agency.

Therapeutic Goals

Reality Therapy aims to help clients:

Clarify their needs and how effectively they are meeting them.

Evaluate current behavior in light of these needs.

Take responsibility for making more effective choices.

Develop a realistic and attainable action plan for change.

Build satisfying relationships, especially in the realm of love and belonging (considered the central psychological need).

Prochaska and Norcross (2007) describe Reality Therapy as a change-oriented, action-centered approach that seeks practical improvements in daily functioning rather than symptom reduction alone.

The Role of the Therapist

The therapist’s role is supportive yet directive. Glasser insisted that therapeutic relationships must be warm, honest, and non-coercive, as clients only change when they trust that the therapist genuinely cares (Corey, 2008). While the therapist does not accept excuses, they also avoid blaming, moralizing, or focusing on psychopathology.

Woolfe and Dryden (1996) note that Reality Therapy aligns with counseling psychology’s emphasis on the therapeutic relationship as a vehicle for change. The therapist offers guidance, feedback, and encouragement while holding clients accountable for their actions.

Therapeutic Process and Techniques

Reality Therapy follows a structured process, typically represented by the “WDEP” system developed by Wubbolding (though not listed in your sources, the WDEP framework is commonly referenced in the works by Corey, Capuzzi & Gross, and Corsini & Wedding).

1. W – Wants

Therapists explore what clients want and how these wants relate to their basic psychological needs (Feltham & Horton, 2006).

2. D – Doing and Direction

Clients examine their current behavior, both internal and external. The focus remains on present choices rather than past causes (Corey, 2008).

3. E – Evaluation

Clients are encouraged to evaluate whether their behaviors are helping or hindering their goals. This step is essential because clients must personally conclude that change is needed (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

4. P – Planning

Action plans must be Simple, Attainable, Measurable, Immediate, Controlled by the client, Committed, and Consistent (SAMIC). Plans focus on specific behavior rather than feelings.

Reality Therapy

Other Core Techniques Include:

Reframing excuses as choices

Confrontation without condemnation

Role-playing and behavioral rehearsal

Contracting to build accountability

Encouragement and positive reinforcement

Reality Therapy avoids:

Dwelling on symptoms

Exploring unconscious motivations

Discussing diagnoses or labels

Focusing on external control (e.g., blaming others)

Rimm and Masters (1987) note that Reality Therapy’s action-oriented style shares similarities with behavior therapy but maintains stronger emphasis on internal motivation.

Applications in Group Counseling

Corey (2008) highlights the approach’s usefulness in group settings. Reality Therapy encourages group members to examine how their behaviors influence others, supporting responsibility and relationship building. Group exercises often involve evaluation, feedback, and collaborative planning.

Because group members witness one another’s efforts to take responsibility, group Reality Therapy can create strong motivation for personal change.

Multicultural Considerations

Reality Therapy’s emphasis on choice and responsibility aligns with many cultural values such as empowerment, community accountability, and self-determination. However, counselors must adapt techniques to avoid assumptions about autonomy or individualism, especially when working with collectivistic cultures (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Feltham and Horton (2006) point out that the approach’s explicit focus on present behavior can be helpful for cultures that emphasize practical problem-solving. Nevertheless, the model may need modification with clients facing systemic oppression, trauma, or external constraints, where choice is limited.

Strengths of Reality Therapy

Practical and action-oriented: Emphasizes concrete changes rather than abstract analysis (Corey, 2008).

Emphasis on responsibility: Empowers clients to take control of their behavior.

Strong therapeutic alliance: Aligns with counseling psychology’s relationship-centered values (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Wide applicability: Used in schools, corrections, addictions counseling, and community mental health (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008).

Non-pathologizing: Avoids labels that may stigmatize or reduce client agency.

Criticisms and Limitations

Despite its strengths, several critiques are documented across counseling literature:

1. Overemphasis on Personal Responsibility

Prochaska and Norcross (2007) argue that the model may inadequately address systemic, environmental, or trauma-related contributors to behavior.

2. Limited Consideration of Unconscious Processes

Psychoanalytic and psychodynamic perspectives often criticize reality therapy for simplifying human complexity (Feltham & Horton, 2006).

3. Not Ideal for Severe Mental Illness

Clients experiencing psychosis, cognitive impairments, or severe mood disorders may require interventions that address biological and neurological factors (Corsini & Wedding, 1995).

4. Possible Cultural Limitations

The model’s Western individualistic assumptions can create barriers with some multicultural populations unless modified (Woolfe & Dryden, 1996).

Reality Therapy and Contemporary Counseling Psychology

Recent scholarship in counseling psychology—such as Gelso & Williams (2022)—emphasizes evidence-based practice, multicultural competence, and integration of theory. Reality Therapy aligns well with these developments when applied flexibly. Its focus on empowerment, client strengths, and collaborative goals resonates with humanistic and positive psychology traditions.

Additionally, the model’s action-oriented planning complements cognitive-behavioral and solution-focused approaches widely used in modern practice.

Conclusion

Reality Therapy remains a highly influential and relevant approach within counseling and psychotherapy. Its emphasis on personal choice, responsibility, relationship-building, and pragmatic action continues to appeal to practitioners across educational, clinical, and community settings. Drawing from humanistic principles while providing a structured, directive framework, the model offers a powerful means for helping clients clarify their needs and create actionable plans for improving their lives.

While not without limitations, Reality Therapy’s enduring presence in the field—highlighted in major counseling psychology texts (Gelso & Williams, 2022; Corey, 2008; Capuzzi & Gross, 2008; Prochaska & Norcross, 2007)—demonstrates its continuing utility. When applied sensitively and with cultural awareness, Reality Therapy can facilitate meaningful behavior change, strengthen interpersonal relationships, and empower clients to meet their fundamental psychological needs in healthier and more effective ways.

References

Ajaya, S. (1989). Psychotherapy: East and West. Himalayan International Institute.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and behavior disorders.

Capuzzi, D., & Gross, D. R. (2008). Counseling and psychotherapy: Theories and interventions (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

Corey, G. (2008). Theory and practice of group counseling. Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Corsini, R. J., & Wedding, D. (1995). Current psychotherapies. F. E. Peacock.

Feltham, C., & Horton, I. (2006). The Sage handbook of counselling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.). Sage.

Gelso, C. J., & Fretz, B. R. (1995). Counseling psychology. Prism Books.

Gelso, C. J., & Williams, E. N. (2022). Counseling psychology. American Psychological Association.

Nelson-Jones, R. (2009). Theory and practice of counselling and therapy (4th ed.). Sage.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2007). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (6th ed.). Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Rimm, D. C., & Masters, J. C. (1987). Behavior therapy: Techniques and empirical findings. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Stewart, I. (2000). Transactional analysis counseling in action. Sage.

Watts, A. W. (1973). Psychotherapy: East and West. Penguin.

Woolfe, R., & Dryden, W. (1996). Handbook of counseling psychology. Sage.

Verma, L. (1990). The management of children with emotional and behavioral difficulties. Routledge.

Veereshwar, P. (2002). Indian systems of psychotherapy. Kalpaz Publications.

Rama, S., Ballentine, R., & Ajaya, S. (1976). Yoga and psychotherapy. Himalayan International Institute.

Ellis, A., & Harper, A. (1975). A new guide to rational living. Prentice-Hall.

Brown, C., & Augusta-Scott, T. (2007). Narrative therapy. Sage Publications.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 19). Reality Therapy and 5 Important Therapeutic Goals of It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/reality-therapy/