What is Cognition?

Cognition refers to the mental processes involved in acquiring knowledge and understanding through experience, senses, and thought. It encompasses a wide range of mental functions and activities that are essential for interpreting, organizing, and acting upon information from the environment. These processes help individuals make sense of the world and form the foundation for learning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

Cognitive functions include, but are not limited to:

- Attending

- Learning

- Remembering

- Memory recall

- Symbolizing

- Categorizing

- Planning

- Thinking

- Reasoning

- Problem-solving

- Creating

- Fantasizing

These mental activities work together to enable individuals to engage effectively with their environments and respond adaptively to various situations (Berk, 2018).

Read More- Social Cognition

What is Cognitive Development?

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), cognitive development is defined as the growth and maturation of thinking processes of all kinds, including perceiving, remembering, concept formation, problem solving, imagining, and reasoning. It reflects the progressive changes in cognitive abilities from infancy through adulthood (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2024).

Cognitive development can be explained in two primary ways:

- Stage-based theories propose that development occurs in distinct, qualitative stages that differ in kind rather than degree (e.g., Piaget).

- Continuous models, such as information-processing theories, suggest that cognitive development is a gradual and cumulative process involving quantitative changes in the efficiency of mental processes.

Two influential approaches to cognitive development are:

- Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

- The Information-Processing Approach

1. Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Jean Piaget, a Swiss developmental psychologist, proposed one of the most influential theories of cognitive development. He emphasized a stage-based model, suggesting that children actively construct knowledge through direct interaction with their environment. According to Piaget, children do not passively receive information; instead, they build mental structures known as schemas through active exploration (Piaget, 1952).

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

Key Assumptions

Piaget’s theory is based on the following assumptions:

- All children pass through four universal stages of cognitive development.

- These stages occur in a fixed, invariant sequence.

- Transition from one stage to another depends on biological maturation and exposure to relevant experiences.

- Cognitive development is driven by the interaction between the child’s innate capacities and environmental demands.

Processes of Cognitive Development

Schemas: Basic mental structures or frameworks that help organize and interpret information. For example, a child may have a schema for “dog” based on seeing a pet dog at home.

Adaptation: The process of adjusting to new environmental demands, achieved through two complementary processes:

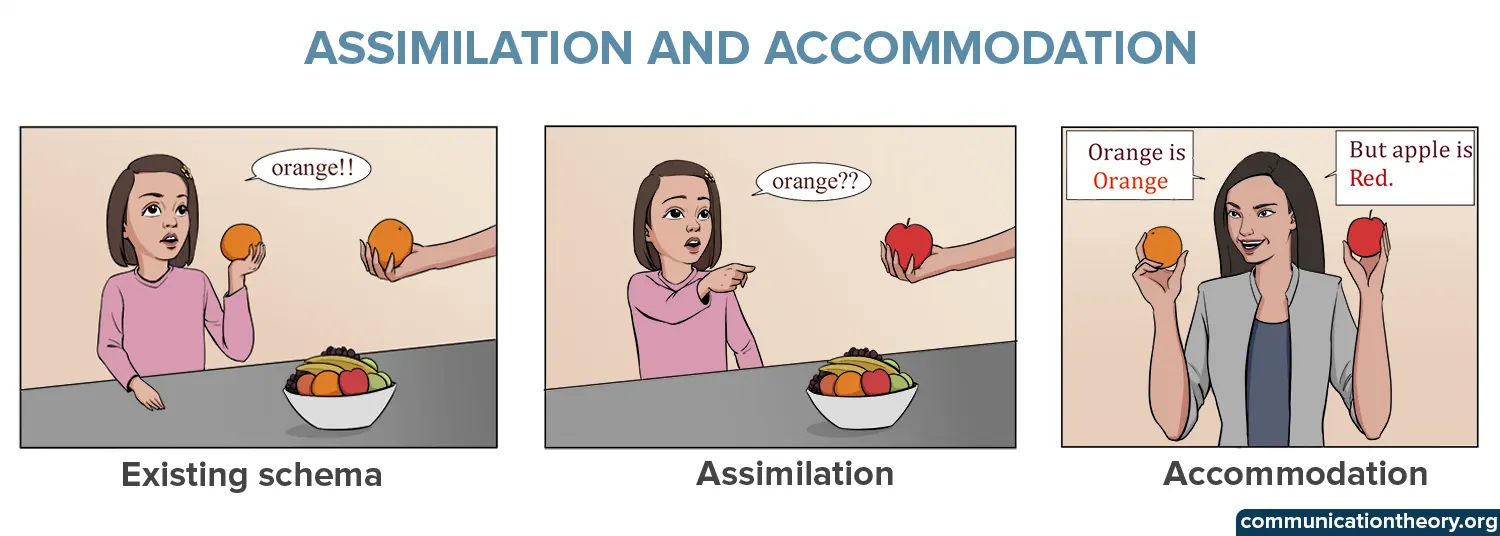

Assimilation: Integrating new experiences into existing schemas.

Accommodation: Modifying existing schemas to incorporate new information.

Equilibration: The process of maintaining cognitive balance. When new information doesn’t fit existing schemas (disequilibrium), it prompts adaptation, leading to a return to equilibrium.

Organization: The internal process of rearranging and linking schemas to form a coherent cognitive system.

Assimilation and Accommodation

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

1. Sensorimotor Stage (0–2 years)

During this stage, infants learn about the world through their senses and actions. Cognitive development begins with simple reflexes and gradually advances to purposeful actions and symbolic thought.

Substages:

- Simple Reflexes (0–1 month)

- Primary Circular Reactions (1–4 months)

- Secondary Circular Reactions (4–8 months)

- Coordination of Secondary Circular Reactions (8–12 months)

- Tertiary Circular Reactions (12–18 months)

- Mental Representation (18–24 months)

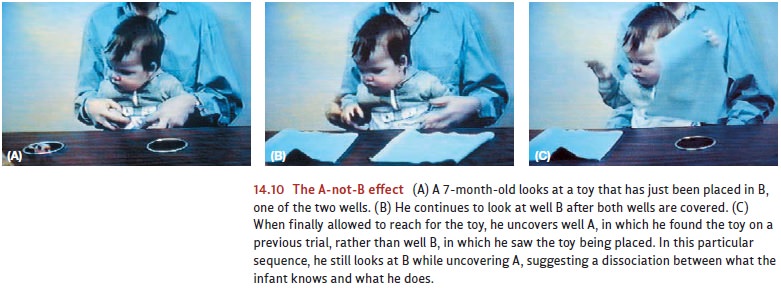

By the end of this stage, infants develop object permanence, the understanding that objects continue to exist even when they are out of sight.

A Not B Task

2. Preoperational Stage (2–7 years)

In this stage, symbolic thinking grows, language use increases, and children begin to engage in pretend play. However, their thinking is still egocentric and illogical.

Key features:

- Egocentrism: Inability to take the perspective of others.

- Animism: Belief that inanimate objects have lifelike qualities.

- Lack of Conservation: Inability to understand that quantity remains the same despite changes in shape or appearance.

- Emerging skills in classification and seriation.

3. Concrete Operational Stage (7–12 years)

Children in this stage begin to think logically about concrete events. They understand the concepts of conservation, reversibility, and classification.

Key characteristics:

- Ability to perform mental operations on tangible objects.

- Mastery of conservation tasks (e.g., volume, number, mass).

- Development of logical reasoning, but still limited to concrete situations.

4. Formal Operational Stage (12–16 years and beyond)

This stage marks the onset of abstract thinking and hypothetical reasoning. Adolescents can now systematically plan, test hypotheses, and use deductive logic.

Abilities include:

- Thinking about possibilities and hypothetical situations.

- Understanding abstract concepts (e.g., justice, love).

- Evaluating the logic of verbal statements without concrete evidence.

2. Information-Processing Approach to Cognitive Development

Unlike Piaget’s stage theory, the information-processing approach views cognitive development as a continuous and gradual improvement in the ways children encode, store, and retrieve information.

Key Components

Encoding: The process by which information is initially recorded in a form usable to memory. Selective attention plays a crucial role in determining which information gets encoded.

Storage: The process of maintaining encoded information in memory over time.

Retrieval: Accessing stored information when needed. Efficient retrieval improves with development and experience.

Automatization

Automatization refers to the degree to which cognitive tasks become automatic with practice. For instance, while learning to walk or use utensils requires attention initially, these activities become automatic over time. Automatic processes free up mental resources for more complex tasks (Feldman, 2017).

Memory Capabilities in Infants

Memory involves three stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval. According to research, infants demonstrate memory abilities that improve with age.

A study by Rovee-Collier (1999) revealed that two-month-old infants could retain information for a few days, while six-month-olds retained memories for up to three weeks.

Infants can be prompted to retrieve lost memories with appropriate reminders, a phenomenon known as reactivation.

Infantile Amnesia

Infantile amnesia refers to the inability of adults to recall memories from the first three years of life. Despite this, some studies suggest that implicit memory may exist from as early as six months (Bauer, 2006).

Individual Differences in Infant Intelligence

Gesell’s Developmental Quotient (DQ)

Arnold Gesell developed one of the earliest tools to assess infant intelligence. The Developmental Quotient (DQ) evaluates an infant’s motor skills, language use, adaptive behavior, and personal-social behavior to identify typical and atypical development (Gesell, 1946).

Bayley Scales of Infant Development

Developed by Nancy Bayley, this tool assesses infants from 2 to 42 months of age. It focuses on two main areas:

- Mental abilities: Memory, perception, problem-solving, and language.

- Motor abilities: Fine and gross motor skills.

While the Bayley Scales are useful for early detection of developmental delays, they are not strong predictors of later intelligence due to the dynamic nature of early development.

Conclusion

Understanding cognition and cognitive development is crucial for grasping how individuals perceive, learn, remember, and solve problems throughout the lifespan. Piaget’s stage theory provides a foundational view of how children construct knowledge, emphasizing qualitative shifts in thinking. On the other hand, the information-processing approach offers a detailed and dynamic account of the mechanisms behind these cognitive changes, emphasizing gradual, quantitative improvements in mental functioning.

Together, these perspectives offer a more holistic understanding of how human thinking evolves from infancy through adolescence and into adulthood.

References

American Psychological Association. (2024). APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org

Bauer, P. J. (2006). Constructing a Past in Infancy: A Neuro-Developmental Account. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(4), 175–181.

Berk, L. E. (2018). Development Through the Lifespan (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Feldman, R. S. (2017). Development Across the Lifespan (8th ed.). Pearson Education.

Gesell, A. (1946). The First Five Years of Life: A Guide to the Study of the Preschool Child. Harper & Brothers.

Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. International Universities Press.

Rovee-Collier, C. (1999). The Development of Infant Memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(3), 80–85.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2022, December 10). 2 Important Theories of Cognitive Development. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/theories-of-cognitive-development/