Introduction

Sleep is a biologically essential state that supports cognitive processing, emotional regulation, metabolic restoration, and immune functioning. When sleep quantity, quality, timing, or architecture are disrupted, the consequences extend beyond fatigue to impaired attention, mood dysregulation, cardiovascular risk, metabolic disturbance, and reduced quality of life. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) identifies a group of sleep-wake disorders that substantially impair daytime functioning; among the most clinically important are Insomnia Disorder, Hypersomnolence Disorder, Narcolepsy, and Breathing-Related Sleep Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Read More: Cognitive Therapy

1. Insomnia Disorder

Insomnia Disorder is defined by persistent difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, or early-morning awakening with inability to return to sleep, accompanied by significant daytime impairment (e.g., fatigue, impaired concentration, mood disturbance). DSM-5 requires symptoms to occur at least 3 nights per week, be present for at least 3 months, and occur despite adequate sleep opportunity (APA, 2013).

Insomnia symptoms are common — transient difficulties affect a large portion of the population at times of stress, while chronic insomnia affects approximately 6–10% of adults. Insomnia increases risk of depression, anxiety, occupational impairment, accidents, and cardiovascular events (Butcher et al., 2014; Sarason & Sarason, 2002).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Insomnia is best understood via a multifactorial model integrating predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors (the 3P model):

- Predisposing factors: trait hyperarousal, family history, personality (e.g., neuroticism), baseline sleep reactivity.

- Precipitating factors: acute stressors (job loss, bereavement, medical illness), shift work, jet lag.

- Perpetuating factors: maladaptive sleep behaviors and cognitions (excessive time in bed, napping, stimulus associations), conditioned arousal (bed/bedroom associated with wakefulness), worry and performance anxiety about sleep (Barlow & Durand, 2005).

Neurobiologically, insomnia is associated with physiological hyperarousal (elevated sympathetic tone, HPA axis activation), increased high-frequency EEG activity during non-rem sleep, and abnormalities in sleep-regulatory neurotransmitters (e.g., GABA, adenosine) (Carson et al., 2007).

Medical comorbidity (chronic pain, endocrine disorders, respiratory disease), psychiatric comorbidity (depression, anxiety, PTSD), and medications/substances (benzodiazepine withdrawal, stimulants, SSRIs, caffeine, alcohol) frequently contribute.

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

Assessment should combine clinical interview, sleep history, sleep diary (2–4 weeks), and screening questionnaires (Insomnia Severity Index). Actigraphy provides objective circadian and sleep–wake pattern data; polysomnography (PSG) is indicated when alternative sleep disorders (obstructive sleep apnea, periodic limb movements, narcolepsy) are suspected or when insomnia is treatment-resistant (APA, 2013).

Differential diagnosis includes sleep apnea (nocturnal gasping), restless legs syndrome (worse at rest, relieved by movement), circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders (delayed sleep phase), medication/substance-induced insomnia, and coexisting psychiatric disorders.

Sleep and Sleep–Wake Disorders

Evidence-based Treatments and Interventions

Some treatments include:

1. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

CBT-I is the treatment of choice for chronic insomnia and produces durable effects superior to pharmacotherapy alone (Barlow & Durand, 2005; Butcher et al., 2014). Core components:

- Sleep restriction therapy: limiting time in bed to approximate actual sleep time, then gradually increasing time to consolidate sleep and improve sleep efficiency.

- Stimulus control: re-associating bed with sleep (go to bed only when sleepy, leave bed if unable to sleep, use bed for sleep/sex only, get up at fixed time).

- Cognitive therapy: identifying and restructuring maladaptive beliefs about sleep (e.g., catastrophizing effects of a poor night).

- Relaxation training: diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, mindfulness.

- Sleep hygiene education: addressing environmental and behavioral contributors (caffeine, naps, light exposure).

CBT-I can be delivered individually, in groups, or via guided digital programs.

2. Pharmacologic Treatments

Medications are appropriate for short-term use or when CBT-I is insufficient/ inaccessible. Classes include:

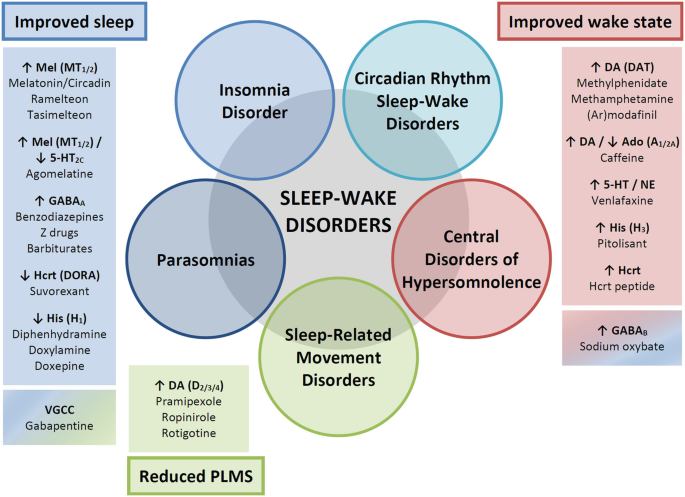

- Benzodiazepine receptor agonists (Z-drugs: zolpidem, zaleplon, eszopiclone): effective for sleep onset/maintenance but risk tolerance, dependence, rebound insomnia, cognitive/motor impairment, and increased fall risk in older adults.

- Benzodiazepines (e.g., temazepam): effective but similar risks.

- Melatonin receptor agonists (ramelteon): suitable for sleep-onset problems with favorable safety.

- Dual orexin receptor antagonists (suvorexant): newer agents that suppress wake-promoting orexin signaling.

- Antidepressants with sedative properties (trazodone, mirtazapine) may be used particularly when comorbid depression/anxiety exists.

- Antihistamines: non-prescription agents provide short relief but daytime sedation and anticholinergic effects limit long-term use.

Medication choice should account for age, comorbidity, risk of dependence, and daytime impairment. Long-term management emphasizes gradual taper and integration with CBT-I.

2. Behavioral and Lifestyle Interventions

Regular sleep–wake schedules, reduced evening stimulant/alcohol use, physical activity (timed earlier in day), bedroom environment optimization (dark, cool, quiet), and managing light exposure (bright morning light when phase advance desired).

4. Treat Comorbidities

Treat pain, psychiatric disorders, sleep apnea, RLS, or medications that disrupt sleep. Integrated care improves outcomes.

Sleep-Wake Disorders

2. Hypersomnolence Disorder

Hypersomnolence Disorder is characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness despite a main sleep period lasting at least 7 hours, with either prolonged sleep episodes (≥9 hours) or recurrent periods of sleep or lapses into sleep, and significant impairment. Sleep inertia (difficulty being fully awake after awakening) is common (APA, 2013).

Chronic hypersomnolence is less common than insomnia but causes substantial occupational and safety risks (e.g., motor vehicle accidents), cognitive impairment, and mood disturbance (Nevid et al., 2014).

Hypersomnolence may be primary (idiopathic hypersomnia) or secondary to medical, neurological, psychiatric, or substance-related causes. Proposed mechanisms include:

- Hypocretin/orexin dysregulation (less prominent than narcolepsy)

- Impaired sleep homeostasis or circadian misalignment

- Residual effects of sleep-disordered breathing or nocturnal sleep fragmentation

- Medication effects (sedatives, anticonvulsants)

- Medical conditions (hypothyroidism, hepatic/renal failure, post-infectious states)

Idiopathic hypersomnia likely involves abnormalities in sleep-promoting systems and poor sleep consolidation.

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

Evaluation includes thorough history, sleep diary, actigraphy, overnight PSG (to exclude sleep apnea or periodic limb movements), and Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) when narcolepsy is considered. Lab tests should screen for thyroid dysfunction, anemia, and other systemic contributors.

Differential diagnosis: narcolepsy (look for cataplexy, sleep-onset REM), sleep apnea (snoring, witnessed apneas), medication/substance effects, major depressive disorder with hypersomnia.

Treatments and Management

1. Pharmacologic Treatments

Wake-promoting agents are mainstays:

- Modafinil / Armodafinil: first-line for excessive daytime sleepiness; increase cortical activation with lower abuse potential than stimulants.

- Stimulants (methylphenidate, amphetamines): effective for severe sleepiness but carry dependence and cardiovascular risk.

- Sodium oxybate (limited use): may consolidate nocturnal sleep and reduce daytime sleepiness for some.

Medication choice depends on severity, comorbidity, and side-effect profile.

2. Behavioral Strategies

- Scheduled naps (short, strategic) can be restorative for some.

- Sleep hygiene and regular sleep–wake times.

- Ergonomic/workplace adjustments; counsel regarding driving and operating machinery.

3. Treat Underlying Causes

If sleep-disordered breathing, metabolic, or medication causes are identified, address them to improve hypersomnolence.

3. Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is a chronic neurological disorder of sleep–wake regulation characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and features such as cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations. DSM-5 distinguishes:

- Narcolepsy type 1: EDS with cataplexy or low hypocretin-1 levels.

- Narcolepsy type 2: EDS without cataplexy and with normal hypocretin levels (APA, 2013).

Narcolepsy is relatively uncommon (estimated prevalence ~0.02–0.05%) but often underdiagnosed; onset typically in adolescence or young adulthood. There may be autoimmune associations and seasonal/ geographical clustering suggesting environmental triggers (Nevid et al., 2014).

Pathophysiology and Etiology

A central mechanism in many cases is loss of hypocretin (orexin)-producing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus, leading to instability between wakefulness and REM sleep. Evidence supports an autoimmune process in genetically susceptible individuals (e.g., HLA-DQB1*06:02 association). Environmental triggers (influenza infections, vaccinations in rare cases) have been implicated historically (Puri et al., 1996).

- Excessive daytime sleepiness with irresistible sleep attacks.

- Cataplexy: sudden, transient loss of muscle tone triggered by strong emotions (laughter, surprise).

- Sleep paralysis: transient inability to move at sleep onset or upon awakening.

- Hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations: vivid dream-like experiences during transitions.

- Fragmented nocturnal sleep and poor sleep consolidation are common.

Assessment and Diagnostic Workup

- Polysomnography (overnight) to exclude other sleep disorders.

- Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) measures daytime sleep propensity and REM onset latency — diagnostic criteria include mean sleep latency ≤8 minutes and two or more sleep-onset REM periods.

- Measurement of CSF hypocretin-1 can confirm hypocretin deficiency (low levels) where available.

- Neurological and psychiatric assessment to rule out mimics.

Treatment and Management

Treatment is symptomatic and individualized, combining pharmacologic and behavioral strategies:

1. Pharmacotherapy for EDS

- Modafinil / Armodafinil: first-line for daytime sleepiness.

- Solriamfetol (dopamine/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) and new agents may be considered where available.

- Amphetamine stimulants when others are ineffective.

2. Treatments for Cataplexy and REM-related symptoms

- Sodium oxybate (gamma-hydroxybutyrate): effective for cataplexy and for consolidating nocturnal sleep.

- Antidepressants with REM-suppressing properties (tricyclics, SSRIs, SNRIs) can reduce cataplexy frequency.

3. Behavioral and Lifestyle Measures

- Scheduled short naps during the day (20–30 minutes).

- Sleep hygiene to consolidate nocturnal sleep.

- Education about driving safety and workplace accommodations.

4. Long-term Considerations

Narcolepsy requires chronic management; psychosocial counseling and vocational planning are important given impact on schooling, employment, and mental health.

4. Breathing-Related Sleep Disorders

This category includes obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), central sleep apnea (CSA), and sleep-related hypoventilation syndromes. OSA is by far the most prevalent and clinically consequential.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)

OSA is defined by repeated episodes of partial or complete upper-airway collapse during sleep resulting in oxygen desaturation and fragmented sleep. Symptoms include loud snoring, witnessed apneas, gasping/choking, excessive daytime sleepiness, morning headaches, and cognitive impairment (Puri et al., 1996).

Prevalence increases with age and obesity; men are affected more commonly, though postmenopausal women’s risk rises. Anatomical risk factors include enlarged tonsils, retrognathia, and nasal obstruction. Medical risk factors include hypothyroidism and neuromuscular disorders.

Sleep-Wake Disorders

Pathophysiology

Intermittent upper-airway obstruction during sleep causes hypoxia/reoxygenation cycles, sympathetic activation, systemic inflammation, and elevated cardiovascular risk (hypertension, arrhythmias, stroke). Sleep fragmentation contributes to daytime sleepiness and neurocognitive deficits.

Diagnosis

Polysomnography (PSG) is diagnostic. The Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) quantifies severity (AHI ≥5 with symptoms considered diagnostic; higher cutoffs for moderate/severe). Home sleep testing may be used where PSG is impractical.

Treatment and Interventions

- Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP): gold standard for moderate–severe OSA; pneumatic splinting of the airway improves oxygenation, sleep continuity, daytime sleepiness, and blood pressure.

- Oral appliance therapy (mandibular advancement devices) for mild–moderate OSA or CPAP intolerance.

- Weight reduction: critical in obese patients; even modest weight loss reduces AHI.

- Positional therapy for supine-predominant OSA.

- Upper airway surgery (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, maxillomandibular advancement) in selected cases or for anatomic lesions (enlarged tonsils).

- Hypoglossal nerve stimulation: an emerging option for selected patients.

Management also addresses cardiovascular comorbidity and daytime functioning; adherence to CPAP is a common challenge requiring education and mask/interface optimization.

Central Sleep Apnea (CSA) and Hypoventilation Syndromes

CSA stems from impaired respiratory drive (neurologic injury, heart failure, opioid therapy) leading to cessation of respiratory effort. Cheyne-Stokes respiration is a variant seen in heart failure. Characterized by inadequate ventilation during sleep (elevated CO₂), as seen in obesity hypoventilation syndrome or neuromuscular disease.

Practical Clinical Considerations, Comorbidities & Safety

- Comorbidity: Sleep disorders often co-exist with mood/anxiety disorders, chronic pain, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. Treat comorbidities concurrently.

- Medication interactions: many psychotropic and non-psychiatric medications affect sleep architecture; review meds.

- Safety: counsel patients on driving, operating machinery, and workplace safety if daytime sleepiness is present.

- Special Populations: older adults have altered sleep architecture and increased medication sensitivity; children present with different symptom profiles (behavioral manifestations of sleepiness).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Alloy, L. B., Riskind, J. H., & Manos, M. J. (2005). Abnormal Psychology: Current Perspectives (9th ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill.

Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (2005). Abnormal Psychology (4th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2014). Abnormal Psychology (15th ed.). Pearson.

Carson, R. C., Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (13th ed.). Pearson.

Nevid, J. S., Rathus, S. A., & Greene, B. (2014). Abnormal Psychology (9th ed.). Pearson.

Puri, B. K., Laking, P. J., & Treasaden, I. H. (1996). Textbook of Psychiatry. Churchill Livingstone.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, R. B. (2002). Abnormal Psychology: The Problem of Maladaptive Behavior (10th ed.). Pearson Education.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 2). 4 Important Sleep-Wake Disorders: Diagnosis, Etiology, Treatments & Interventions. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/sleep-wake-disorders/