Introduction

Classical psychoanalysis, pioneered by Sigmund Freud in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, laid the foundation for modern psychotherapeutic thought and practice. It remains one of the most influential systems of psychotherapy, influencing diverse schools of psychodynamic and humanistic counseling that followed (Gelso & Fretz, 1995; Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

Classical psychoanalysis views human behavior as deeply influenced by unconscious processes, early developmental experiences, and intrapsychic conflicts. Over time, numerous psychoanalytic and psychodynamic schools have emerged, each modifying and expanding Freud’s original ideas while retaining certain core elements.

Read More: Psychoanalysis

Historical Background of Classical Psychoanalysis

Freud’s development of psychoanalysis was initially rooted in his work with patients experiencing hysteria and neurosis in Vienna. Drawing on clinical observations, Freud proposed that psychological symptoms arise from unresolved unconscious conflicts originating in childhood (Corsini & Wedding, 1995). Through techniques such as free association, dream analysis, and transference interpretation, Freud sought to uncover and resolve these repressed experiences.

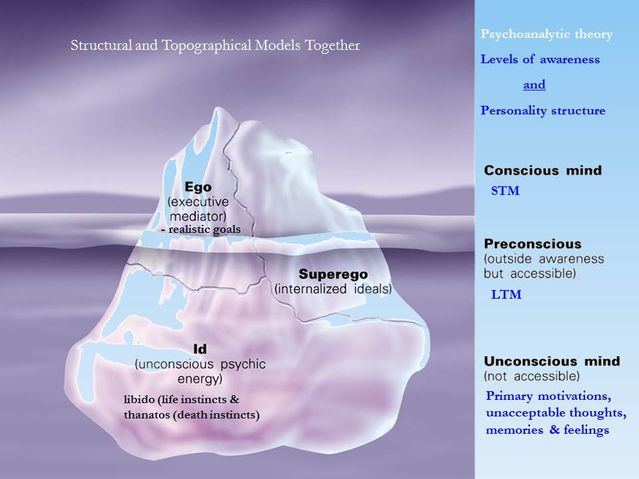

Freud’s topographical model of the mind—dividing mental life into the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious—provided an enduring framework for understanding human motivation (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007). Later, his structural model of personality, encompassing the id, ego, and superego, became central to psychoanalytic theory. The id represents instinctual drives, the ego mediates between internal desires and external reality, and the superego internalizes societal and parental standards. Together, these structures create dynamic tensions that manifest in behavior and symptom formation.

Topographic Model of Mind

Freud’s work also introduced the psychosexual stages of development: oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008). Fixations or conflicts at any of these stages could lead to specific personality traits or psychological disorders. This developmental model underscored Freud’s belief that adult psychopathology has its origins in early childhood experiences.

Core Concepts in Classical Psychoanalysis

Several interrelated concepts define classical psychoanalysis. The first is the unconscious, the realm of thoughts, feelings, and memories outside conscious awareness yet exerting significant influence over behavior. The dynamic nature of the psyche, wherein unconscious drives constantly seek expression and are countered by defensive mechanisms, is another hallmark (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Freud’s notion of defense mechanisms—such as repression, projection, displacement, and rationalization—illustrates how the ego protects the individual from anxiety and internal conflict (Rimm & Masters, 1987). The analytic process aims to make these defenses conscious so that clients can confront their underlying issues more directly.

Defense Mechanisms

A third essential feature is transference, the process by which clients project feelings from past relationships onto the therapist. This phenomenon allows the re-experiencing of unresolved emotional conflicts within the therapeutic relationship (Corey, 2008). The therapist’s awareness of countertransference—his or her own emotional reactions to the client—is equally crucial to maintaining therapeutic objectivity and empathy (Gelso & Fretz, 1995).

Another core technique is free association, in which the client verbalizes all thoughts without censorship. This process enables the surfacing of unconscious material. Similarly, dream interpretation—termed the “royal road to the unconscious”—allows symbolic understanding of latent wishes and fears (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

The Analytic Setting and Therapeutic Process

The classical psychoanalytic setting emphasizes neutrality, anonymity, and abstinence on the part of the analyst. The client, typically meeting multiple times per week while reclining on a couch, is encouraged to speak freely while the analyst listens interpretively. This structure minimizes external distractions and encourages regression and transference development (Corsini & Wedding, 1995).

Interpretation is the central intervention. Through carefully timed interpretations, the analyst helps the client gain insight—the conscious recognition of previously unconscious conflicts. Insight, combined with the emotional re-experiencing of those conflicts in the analytic relationship, produces therapeutic change (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008).

The process is gradual, involving resistance, working through, and integration. Freud viewed resistance as a manifestation of the ego’s defense against painful awareness. Working through involves repeatedly confronting and resolving these resistances until genuine psychological change occurs.

Common Elements among Psychoanalytic Approaches

Despite the diversification of psychoanalytic theory into object relations, ego psychology, self psychology, and relational psychoanalysis, several common elements persist across all psychoanalytic orientations (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

- Emphasis on the Unconscious: All psychoanalytic schools agree that unconscious processes shape behavior, emotion, and cognition. Whether viewed in terms of repressed instinctual drives (Freud), internalized object relations (Klein), or self-structures (Kohut), the unconscious remains central.

- Importance of Early Development: Psychoanalytic approaches consistently emphasize the formative influence of early life experiences. Childhood relationships, particularly with primary caregivers, are believed to establish internal templates that affect later interpersonal patterns (Feltham & Horton, 2006).

- Repetition and Patterns: A common psychoanalytic theme is the repetition of maladaptive relational patterns. This “repetition compulsion” manifests in transference and is worked through in therapy to achieve new ways of relating (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

- The Therapeutic Relationship: Across psychoanalytic theories, the relationship between therapist and client is both a means and an object of exploration. Contemporary models, such as relational psychoanalysis, emphasize the co-constructed nature of this relationship and its reparative potential (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

- Insight and Interpretation: Regardless of theoretical nuances, gaining insight into unconscious motives remains a shared goal. Interpretation facilitates awareness and integration of previously repressed material, leading to personality restructuring (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008).

- Defenses and Resistance: The recognition of defenses and resistance is fundamental across all psychoanalytic traditions. Analysts help clients identify and modify these unconscious protective strategies that hinder growth and authenticity (Corsini & Wedding, 1995).

- Working Through: The process of repeatedly analyzing conflicts, transference reactions, and defenses—known as “working through”—is essential for internalizing insight and achieving lasting change.

Ego Psychology and Beyond

Following Freud, ego psychology (Hartmann, Anna Freud) expanded on the adaptive and integrative functions of the ego. The ego was no longer viewed merely as a mediator but as a positive agent of mastery and adaptation (Corsini & Wedding, 1995).

Object relations theorists (e.g., Klein, Fairbairn, Winnicott) shifted the focus from instinctual drives to internalized relationships. According to this view, individuals internalize mental representations of significant others, which influence subsequent relationships and emotional functioning (Feltham & Horton, 2006).

Object Relations Theory

Self psychology (Kohut) emphasized the development of a cohesive self through empathic attunement and “selfobject” relationships. Relational psychoanalysis further evolved to stress mutual influence between therapist and client, integrating intersubjective and humanistic perspectives (Gelso & Williams, 2022).

Contemporary Relevance in Counseling Psychology

Although classical psychoanalysis is less commonly practiced in its pure form, its principles continue to inform counseling psychology, particularly through psychodynamic therapies. Modern counseling integrates psychoanalytic ideas with empirical methods and multicultural awareness (Gelso & Williams, 2022; Woolfe & Dryden, 1996).

Techniques such as exploring client narratives, attending to transference, and fostering insight are now adapted for shorter-term and more goal-directed therapy. The enduring value of psychoanalysis lies in its comprehensive understanding of personality development, motivation, and the therapeutic relationship.

Contemporary therapists recognize that insight alone may not suffice for change; integration with cognitive, behavioral, and experiential approaches can enhance outcomes (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007). Nevertheless, the psychoanalytic emphasis on self-understanding and emotional depth remains indispensable.

Critiques and Limitations

Despite its influence, classical psychoanalysis has faced substantial critique. It has been criticized for being deterministic, elitist, and lacking empirical validation (Capuzzi & Gross, 2008). The lengthy and costly analytic process is impractical for many clients, and Freud’s focus on sexuality and patriarchal biases has been challenged by feminist and cultural theorists (Feltham & Horton, 2006).

Modern psychoanalytic practitioners have responded by increasing flexibility, embracing brief psychodynamic models, and incorporating evidence-based research (Gelso & Williams, 2022). The evolution of the field demonstrates its adaptability and continued relevance to counseling psychology.

Conclusion

Classical psychoanalysis, as established by Freud, represents the cornerstone of modern psychotherapy. Its central concepts—the unconscious, defense mechanisms, transference, and insight—continue to inform diverse psychoanalytic and psychodynamic frameworks. Despite significant theoretical evolution, all psychoanalytic approaches share common principles: the enduring influence of unconscious processes, early development, relational patterns, and the transformative power of the therapeutic relationship.

Counseling psychology, while integrating broader paradigms, retains these insights as vital tools for understanding human behavior and facilitating psychological growth. The historical and conceptual continuity of psychoanalysis underscores its lasting impact as both a theory of mind and a method of healing.

References

Capuzzi, D., & Gross, D. R. (2008). Counseling and psychotherapy: Theories and interventions (4th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Corey, G. (2008). Theory and practice of group counseling. Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Corsini, R. J., & Wedding, D. (Eds.). (1995). Current psychotherapies. F. E. Peacock.

Feltham, C., & Horton, I. E. (Eds.). (2006). The Sage handbook of counselling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Gelso, C. J., & Fretz, B. R. (1995). Counselling psychology. Prism Books Pvt. Ltd.

Gelso, C. J., & Williams, E. N. (2022). Counseling psychology. American Psychological Association.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2007). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (6th ed.). Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Woolfe, R., & Dryden, W. (Eds.). (1996). Handbook of counseling psychology. Sage Publications.

Rimm, D. C., & Masters, J. C. (1987). Behavior therapy: Techniques and empirical findings. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 6). Classic Psychoanalysis and 5 Common Elements Across Psychoanalysis Approaches. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/psychoanalysis-common-elements/