Introduction

Aging is a universal process, but its meaning, experience, and consequences are deeply shaped by cultural and social contexts. In the Indian perspective, the process of growing old is viewed through a lens that blends traditional values, spiritual philosophy, and rapidly changing social realities. Unlike Western societies, where individualism and independence are emphasized, Indian cultural traditions place family, interdependence, and spirituality at the center of the aging experience (Hurlock, 1981; Eyetsemitan & Gire, 2003).

Ageing in India

India today faces a demographic transition: the elderly population is growing rapidly due to increased life expectancy and declining fertility rates. According to projections, by 2050 India will have one of the largest elderly populations in the world (Schulz, 2006). This shift raises critical questions about the health, psychological well-being, and socio-economic conditions of older adults.

Read More: Geropsychology

1. Cultural Context of Aging in India

Traditionally, Indian society has revered the elderly as custodians of wisdom, morality, and cultural values. The joint family system historically ensured that elders remained integrated within the household, where they provided guidance and maintained authority over younger generations (Hurlock, 1981). Respect for elders is ingrained in religious and cultural practices, evident in gestures such as touching elders’ feet for blessings.

Modern Transitions

However, rapid urbanization, migration, and the rise of nuclear families have altered these dynamics. With younger generations moving to cities or abroad for education and work, many elders face social isolation and declining authority (Eyetsemitan & Gire, 2003). The erosion of traditional caregiving structures has forced a rethinking of how Indian society supports its aging population.

2. Health and Psychological Issues Among Indian Elders

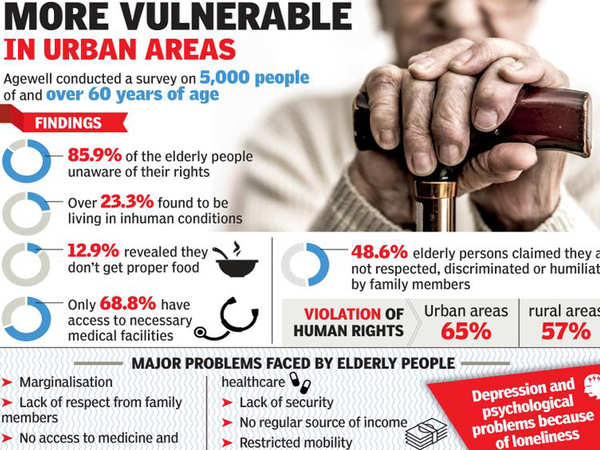

Older adults in India face an increased burden of chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, and cardiovascular disorders (Taylor, 1999). Limited access to healthcare, especially in rural areas, exacerbates these challenges. Preventive healthcare remains underdeveloped, with elders often seeking medical attention only during advanced stages of illness.

Mental Health and Loneliness

Psychologically, Indian elders experience a spectrum of emotions. While many exhibit resilience and adaptability, loneliness and depression are increasingly common, particularly among urban elderly who live apart from their children (Feldman & Babu, 2011). Comer (2007) notes that depression in older adults often manifests through somatic complaints—fatigue, headaches, or pain—making diagnosis challenging in the Indian healthcare context, where mental health literacy is low.

Coping Mechanisms

Despite these difficulties, Indian elders often cope through reliance on family ties, community networks, and spiritual practices. This combination of social and spiritual support provides a buffer against psychological stress (Johnson & Walker, 2016).

3. Family, Community, and Social Support

The family remains the cornerstone of support for older adults in India. Traditionally, children are expected to care for parents in their old age, a duty often reinforced by cultural and religious norms (Birren & Schaie, 2001). Even as nuclear families become more common, many older adults continue to live with or rely on their children for financial, emotional, and caregiving support.

Community and Informal Networks

Community support also plays a vital role. Religious congregations, senior citizen associations, and neighborhood networks offer avenues for social participation and companionship (Feldman & Babu, 2011). Such networks are particularly important for elders whose children live abroad or in distant cities.

Challenges in Social Support

However, weakening family ties and changing values pose significant challenges. Elder neglect and abuse, though underreported, are rising concerns (Schulz, 2006). Additionally, older women, particularly widows, often face higher levels of vulnerability due to gender-based inequalities in access to resources and decision-making.

4. Spiritual and Philosophical Dimensions of Aging

A unique feature of the Indian perspective on aging is its spiritual foundation. The Hindu philosophy of life divides existence into four ashramas (stages): brahmacharya (student life), grihastha (householder), vanaprastha (retirement), and sannyasa (renunciation). Aging is associated with vanaprastha and sannyasa, stages where individuals gradually withdraw from material pursuits and focus on spiritual growth (Hurlock, 1981).

Four Ashramas Retreived From https://graceshinduismwebsitee.weebly.com/ethical-systems.html

Spiritual Coping

Spirituality offers comfort and meaning to older adults in India. Practices such as meditation, prayer, pilgrimage, and engagement in religious rituals are common ways of coping with the anxieties of aging, illness, and death (Johnson & Walker, 2016). Spiritual beliefs also promote acceptance of mortality, framing it as a natural transition rather than a crisis.

Cross-Cultural Significance

Unlike Western models that often emphasize independence and productivity, the Indian model situates aging within a moral and spiritual journey. This orientation highlights resilience and acceptance, even amid physical decline (Eyetsemitan & Gire, 2003).

5. Economic and Policy Challenges

India’s elderly population faces significant economic challenges. Many older adults, especially in rural areas, lack formal pensions or savings, making them financially dependent on their children (Eyetsemitan & Gire, 2003). With shrinking family sizes and increased migration, economic insecurity is becoming a widespread concern.

Aging in India

Government Policies

The Government of India has introduced several measures, such as the National Policy on Older Persons (1999), Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act (2007), and various pension schemes. However, gaps remain in implementation, coverage, and awareness (Schulz, 2006). Access to social security is often limited to organized-sector workers, leaving the majority of elderly in the informal sector without protection.

Institutional Care

Unlike in the West, institutional care in India is limited and often stigmatized. Old age homes are increasing, but many elders view them as symbols of neglect or abandonment. The cultural preference remains family-based care, though the sustainability of this model is uncertain in a rapidly modernizing society (Birren & Schaie, 2001).

Indian vs. Western Perspectives

Both Indian and Western models recognize the physical, cognitive, and emotional challenges of aging. In both contexts, interventions such as physical exercise, mental stimulation, and social support are recognized as protective factors.

Differences

- Family vs. Independence: Western societies emphasize independence and self-reliance, while Indian society emphasizes interdependence and family care.

- Spiritual Orientation: Indian elders often interpret aging as a spiritual journey, while Western models tend to view it through psychological and medical frameworks (Johnson & Walker, 2016).

- Institutional Care: Western societies normalize institutional care, whereas in India it is often stigmatized (Eyetsemitan & Gire, 2003).

These differences highlight the importance of culturally sensitive approaches to gerontology.

Toward a Holistic Indian Model of Aging

To adequately support its growing elderly population, India must develop a holistic model of aging that combines:

- Cultural Strengths: Reinforcing family values, intergenerational bonding, and spirituality.

- Modern Support Systems: Expanding healthcare, pensions, and community-based services.

- Social Awareness: Combating ageism, elder neglect, and gender inequalities.

- Global Adaptation: Learning from Western policies while adapting them to Indian cultural realities.

Such a model would balance tradition with modernity, ensuring dignity and well-being for India’s aging population.

Conclusion

The Indian perspective on aging reflects a rich interplay of tradition, spirituality, family, and community. While demographic and social transitions pose new challenges—health burdens, economic vulnerabilities, and weakening family support—Indian elders also benefit from cultural resources that foster resilience and meaning in later life.

Spiritual frameworks such as the ashrama system, strong familial expectations, and community networks distinguish the Indian experience from Western models. Yet, policy and institutional reforms are urgently needed to address economic insecurity and health disparities.

Aging in India is therefore not merely a biological process but a deeply cultural, spiritual, and social journey. By integrating traditional values with modern policies, India can develop a comprehensive model of aging that ensures not only survival but dignity, respect, and fulfillment in later years.

References

Birren, J. E., & Schaie, K. W. (2001). Handbook of the Psychology of Aging (5th Ed.). Academic Press: London.

Comer, R. J. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (6th Ed.). Worth Publishers.

Elizabeth, B. Hurlock. (1981). Developmental Psychology: A Life-Span Approach (5th Ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill: Delhi.

Eyetsemitan, F. E., & Gire, J. T. (2003). Aging and Adult Development in the Developing World: Applying Western Theories and Concepts. Library of Congress.

Feldman, R. S., & Babu, N. (2011). Discovering the Life Span. Pearson.

Johnson, M., & Walker, J. (2016). Spiritual Dimensions of Aging. Cambridge University Press: UK.

Schulz, R. (2006). The Encyclopaedia of Aging: A Comprehensive Resource in Gerontology and Geriatrics (4th Ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

Taylor, S. E. (1999). Health Psychology (4th Ed.). McGraw-Hill International.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 28). Indian Perspective to Aging and 5 Important Perspectives to It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/indian-perspective-to-aging/