Introduction

Mīmāṃsā, one of the six orthodox (āstika) schools of Indian philosophy, is primarily known for its deep engagement with the ritualistic and exegetical interpretation of the Vedas. However, beneath this ritualistic surface lies a structured psychological framework.

Mīmāṃsā contributes significantly to Indian psychological thought through its treatment of the human self, the nature of knowledge, the psychophysical structure of human beings, and the processes of cognition and perception. Developed chiefly by scholars like Jaimini and Kumārila Bhaṭṭa, the Mīmāṃsā system provides an integrated view of personality that merges ethical responsibility with cognitive functioning.

Read More- Indian Psychology

Philosophical Foundation of Mīmāṃsā

Mīmāṃsā is traditionally divided into two branches: Pūrva Mīmāṃsā and Uttara Mīmāṃsā (the latter better known as Vedānta). The focus here is on Pūrva Mīmāṃsā, which regards the Vedas as eternal and authoritative, and holds that performing prescribed actions (karma) leads to the attainment of desirable ends, including heaven (svarga).

Mimamsa Philosophy

Unlike schools that emphasize metaphysical liberation (mokṣa), Mīmāṃsā highlights duty (dharma) and ritual action as the primary goals of life. Yet, this does not negate its interest in the workings of the mind and the structure of human experience.

According to Safaya (1976), Mīmāṃsā psychology is inherently action-centered, viewing human life through the lens of ritual performance, ethical responsibility, and the acquisition of valid knowledge (pramāṇa).

Factors of Personality

The concept of puruṣa (person) in Mīmāṃsā is a composite of physical, mental, and spiritual elements. Human beings are considered conscious agents who act, experience results, and pursue value-laden goals.

The Self (Ātman)

The ātman is regarded as a permanent, conscious, and autonomous entity. It is the locus of knowledge, action, memory, and desire. Unlike the non-conscious self proposed in Vaiśeṣika, Mīmāṃsā conceives of the self as an inherently active knower and doer (Safaya, 1976, p. 150).

Mīmāṃsā posits that the self continues through various lifetimes, bearing the karmic imprints of previous actions. These karmic residues influence the formation of personality traits and behavioral tendencies, suggesting a continuity of character across births.

Role of Ethical and Volitional Elements

Personality is shaped by:

- Karma (action): which defines moral identity.

- Icchā and dveṣa (desire and aversion): which drive volition.

- Buddhi (intellect): which guides reasoning.

- Smṛti (memory): which supports learning and reflection.

- Pratyaya (awareness): a basic state of knowing.

The emphasis on ethical action aligns with the school’s ritualist doctrine. As Safaya (1976) explains, “The self in Mīmāṃsā is not a passive witness but a dynamic agent who engages in actions, reaps results, and undergoes experience” (p. 150).

The Psychophysical System

Mīmāṃsā maintains a dualistic view of the human constitution. It identifies the following key elements:

The Body (Śarīra)

The physical body is a material instrument for carrying out actions. It is perishable and serves as the vehicle for the self. However, it is not the self itself. The self uses the body as a means to act and experience (Safaya, 1976).

The Mind (Manas)

The manas is a subtle, internal organ necessary for mediating between the self and the sensory world. It is atomic and momentary but plays a central role in psychological processes such as:

- Coordination of sensory data.

- Attention and selective focus.

- Internal perception (e.g., pleasure, pain).

- Volition and intention (Safaya, 1976, p. 152).

The Sense Organs (Indriyas)

Mīmāṃsā recognizes five sensory faculties and five action faculties:

- Jñānendriyas (organs of knowledge): eye, ear, skin, tongue, nose.

- Karmendriyas (organs of action): hands, feet, speech, excretory and reproductive organs.

These function in coordination with manas and ātman to generate experience.

Cognition (Jñāna)

Mīmāṃsā is renowned for its epistemological rigor. It classifies pramāṇas (means of valid knowledge) as:

- Pratyakṣa (perception)

- Anumāna (inference)

- Upamāna (comparison)

- Śabda (verbal testimony)

Each cognition (jñāna) is an event where the self, using the mind and sense organs, comes into contact with an object.

According to Safaya (1976), cognition is not a property of the body or mind but of the self. The self alone is the true knower (jñātṛ) (p. 151). Cognition is considered valid (pramā) when it reveals the object as it truly is.

Process of Cognition

The process involves:

- Contact between sense organ and object.

- Attention of the mind.

- Awareness by the self.

The result is a valid cognition (yathārtha jñāna), which then leads to further judgment or action.

Wrong Cognition

Mīmāṃsā’s approach is realist and intentional — cognition always involves a subject, an object, and a relational awareness (Safaya, 1976).

Theory of Perception (Pratyakṣa)

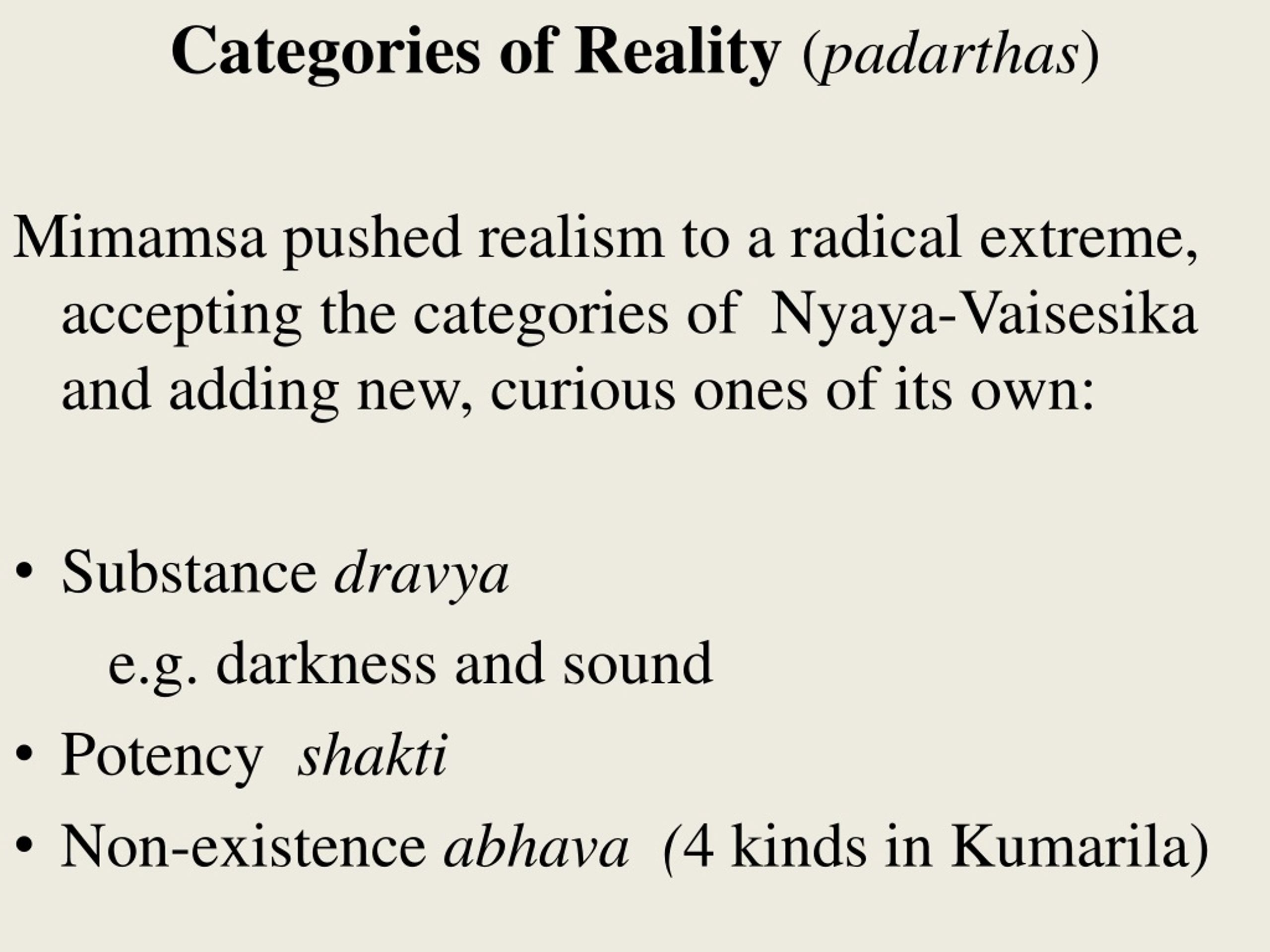

Catagories in Mīmāṃsā

Nature of Perception

Perception is immediate, non-inferential, and arises when sense organs come into direct contact with objects. The Mīmāṃsā view divides perception into:

- Nirvikalpaka pratyakṣa: indeterminate perception, devoid of conceptual content.

- Savikalpaka pratyakṣa: determinate perception, involving classification or recognition.

As Safaya (1976) describes, “Perception is not merely sensory in basis, but structured by attention and shaped by judgment” (p. 152).

Internal Perception

Mīmāṃsā also acknowledges inner experiences — such as hunger, pain, joy, desire — as perceptual. These are known through manas and are valid forms of cognition. This broadens the definition of perception beyond mere external stimuli.

Errors in Perception

Illusory perceptions (e.g., mistaking a shell for silver) are attributed to faulty sense-object relations or past experiences influencing judgment. The distinction between valid and invalid perceptions reinforces the emphasis on pramāṇas.

Conclusion

Mīmāṃsā, while often identified with ritual exegesis, offers a rich psychological framework that integrates metaphysics, ethics, and cognition. It presents the self as an active moral agent, participating in the world through action, memory, perception, and cognition. Its analysis of the mind and knowledge offers insights parallel to modern psychology, especially in terms of attention, sensory processing, and error correction.

Through its focus on karma, buddhi, and jñāna, Mīmāṃsā constructs a model of human personality that is dynamic, ethical, and grounded in the real world — a unique contribution to both philosophy and psychology.

References

Safaya, R. (1976). Indian psychology. Motilal Banarsidass.

Sharma, C. (1991). A critical survey of Indian philosophy (14th ed.). Motilal Banarsidass.

Bhattacharyya, H. (1956). The fundamentals of Indian philosophy. The World Press.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, May 14). Mīmāṃsā and 4 Important Concepts Within It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/mima%e1%b9%83sa-and-4-important-concepts-within-it/