Introduction

Parasomnias are disruptive sleep-related disorders in which undesirable physical, emotional, or sensory events occur during sleep or while transitioning between sleep and wakefulness. They are not disorders of sleep quantity, but disorders of sleep state regulation. In parasomnias, parts of the brain involved in consciousness, motor control, and autonomic functioning may become active at inappropriate times, leading to complex and sometimes dangerous behaviors.

Sleep Disorders

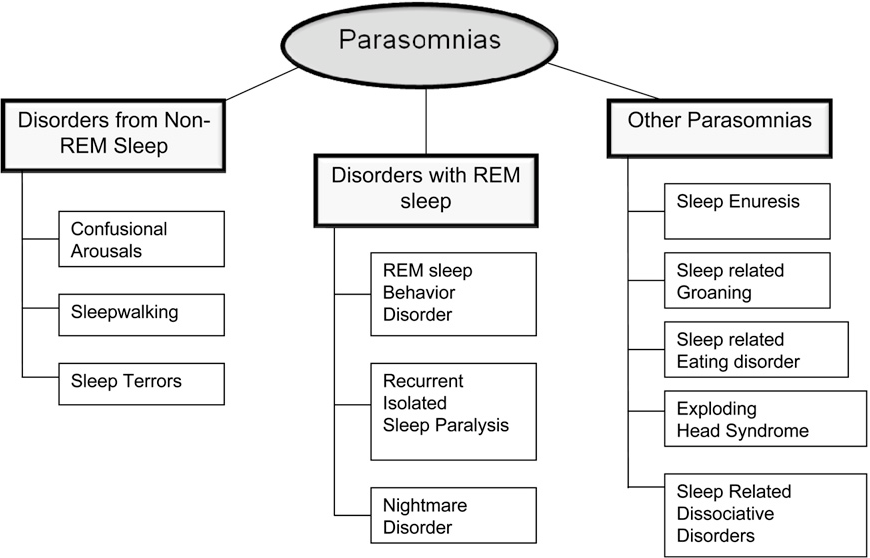

DSM-5 (APA, 2013) categorizes parasomnias based on the sleep stage from which they arise:

- Non-REM (NREM) Sleep Arousal Disorders

- REM Sleep-Related Parasomnias

- Other parasomnias/sleep-related movement disorders (e.g., RLS)

These disorders often reflect a breakdown in the normal inhibition that keeps the body still during sleep. The complexity and unpredictability of parasomnias make them clinically significant, requiring multidisciplinary evaluation including neurology, psychiatry, and sleep medicine.

Read More: Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder

Non-REM Sleep Arousal Disorders

These disorders occur during deep slow-wave sleep (Stages 3–4 NREM). They involve incomplete arousal—the brain is partially awake and partially asleep. This mixed state leads to confusion, limited consciousness, and automatic behaviors.

The two major NREM parasomnias are sleepwalking and sleep terrors.

Parasomnias

1. Sleepwalking (Somnambulism)

A disorder involving episodes of rising from bed and walking or performing complex behaviors while still in deep NREM sleep.

- Eyes open but glassy: Contrary to popular belief, sleepwalkers’ eyes may be open, but their gaze is unfocused.

- Purposeful-seeming behavior: Individuals may dress, eat, open doors, rearrange items, or even drive cars, despite being asleep.

- Minimal responsiveness: They rarely answer questions coherently and seem “distant.”

- Amnesia: Upon awakening, there is little or no recall of events because the brain was never fully conscious.

- Confusion on awakening: If woken abruptly, the person may appear disoriented, irritable, or frightened.

- Duration: Episodes can last seconds to up to 30 minutes.

- Triggers: Sleep deprivation, stress, alcohol, fever, noise, or poor sleep scheduling.

Pathophysiology

Research shows:

- Hyperarousal during deep sleep: The brain’s motor areas activate while higher cortical regions remain asleep.

- Impaired slow-wave sleep regulation: Children have more deep sleep, increasing vulnerability.

- Genetic predisposition: First-degree relatives have a significantly higher risk. Studies show heritability rates of 50–60% (Butcher et al., 2014).

- Immature neural networks: In children, incomplete neurological development increases risk.

Differential Diagnosis

- Nocturnal seizures

- REM-Sleep Behavior Disorder

- Dissociative episodes

- Alcohol-related blackouts

Treatment

The treatment includes:

1. Behavioral Interventions

- Keeping a fixed sleep schedule

- Eliminating sleep deprivation

- Avoiding screens before bed

- Anticipatory awakenings: waking the person 15 minutes before predicted episode time to break the cycle

- Stress management techniques

2. Safety Measures

- Removing sharp objects

- Securing windows and doors

- Using alarms on doors

- Avoid bunk beds for children

3. Medication

- Benzodiazepines reduce deep sleep, lowering episode frequency

- SSRIs if episodes triggered by anxiety or stress

- Treating co-existing sleep apnea or RLS reduces nighttime arousals that trigger sleepwalking

2. Sleep Terrors (Night Terrors)

Sudden episodes of intense panic during sleep, involving loud screaming, autonomic arousal, and unresponsiveness to comfort. Unlike nightmares, individuals do not become fully awake, and recall is poor.

- Sudden scream: The event begins abruptly with a loud shriek.

- Intense physiological arousal:

- Rapid heartbeat

- Sweating

- Trembling

- Dilated pupils

- Extreme fear and agitation: The person may thrash or run, attempting to escape a perceived threat.

- Difficulty waking: Attempting to awaken the person may worsen agitation.

- Amnesia: Limited recall differentiates it from nightmares.

- Timing: Occur in early night during deep sleep.

Sleep terrors are particularly traumatic for family members who witness them.

Etiology

Some etiology include:

1. Biological Factors

- Genetic predisposition (familial clustering is high)

- Immature CNS mechanisms in children

- Overactivity of autonomic nervous system during arousal

2. Precipitating Factors

- Fever, illness

- Sleep deprivation

- Irregular sleep timetable

- Emotional stress

- Medications affecting deep sleep (antihistamines, sedatives)

Treatment

Some more treatments include:

- Ensuring adequate sleep to reduce NREM sleep pressure

- Relaxation techniques (deep breathing, guided imagery)

- Anticipatory awakening

- Psychotherapy if episodes reflect stress or trauma

- Clonazepam for severe or hazardous episodes

3. Nightmare Disorder

Recurrent, vivid, dysphoric dreams that cause abrupt awakening during REM sleep. Unlike terrors, the individual becomes fully awake and immediately alert, with clear memory of the dream’s contents.

- Emotionally intense dreams: Often involve danger, helplessness, humiliation, or existential threats.

- Detailed recall: Dream narratives are usually complex and coherent.

- No confusion: Person awakens rapidly and is oriented.

- Impairment: Can lead to fear of sleep, insomnia, distress, avoidance of REM sleep.

- Daytime anxiety: Frequent nightmares are associated with higher daytime psychological symptoms.

Etiology

The etiology includes:

Psychological Factors

- PTSD is one of the strongest triggers

- Anxiety disorders increase REM-based dream intensity

- Depression contributes to negative dream content

- History of childhood trauma is correlated

Biological Factors

- REM sleep dysregulation

- Hyperactivation in the amygdala during REM

- Lower serotonin may worsen dream vividness

Substance-Induced Factors

- Alcohol withdrawal increases REM pressure

- SSRIs and beta-blockers may intensify dreams

Treatment

Some treatments include:

1. Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT)

- Rewriting the nightmare with a non-threatening ending

- Practicing the new imagery daily

- Reduces frequency and emotional intensity

2. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- Addresses stress and anxiety triggers

- Improves sleep quality and reduces intrusive thoughts

3. Medication

- Prazosin for PTSD nightmares

- Adjusting medications that worsen REM sleep

4. REM-Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD)

RBD is a disorder where the usual REM muscle paralysis (REM atonia) is absent. This allows individuals to physically enact vivid dreams, sometimes violently.

- Vocalizations: yelling, talking, laughing, crying

- Movements: punching, kicking, running, jumping out of bed

- Injury: risk to self or bed partner is high

- Occurs later in night when REM sleep dominates

- Clear dream recall

- Episodes often match dream content (e.g., “fighting,” “running from danger”)

Strong Neurological Associations

RBD is a major predictor of neurodegenerative disorders, especially:

- Parkinson’s disease

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Multiple system atrophy

Up to 80% of older adults with RBD eventually develop a synuclein-related neurodegenerative condition (Puri et al., 1996).

Etiology

- Degeneration of brainstem structures responsible for REM atonia

- Dopaminergic dysfunction

- Associated with use of antidepressants (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs)

- Alcohol withdrawal

- Structural brain lesions

Diagnosis

- Polysomnography: mandatory for confirming loss of REM atonia

- Dream enactment must correlate with REM sleep

Treatment

Some treatments include:

Medication

- Clonazepam stabilizes REM sleep

- Melatonin reduces dream enactment with fewer side effects

Environmental Safety

- Padding floors

- Removing sharp objects

- Using separate beds if severe

5. Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS)

While not a parasomnia per DSM-5, it significantly disturbs sleep and often occurs alongside parasomnias. A neurological sensorimotor disorder with an uncontrollable urge to move the legs, often accompanied by uncomfortable sensations described as tingling, crawling, pulling, or aching.

- Worse during inactivity (evening or nighttime)

- Temporary relief through movement

- Causes significant sleep onset difficulties

- Nighttime leg jerks (periodic limb movements)

- Daytime sleepiness and fatigue

Etiology

Some etiology include the following:

Biological Factors

- Central iron deficiency (low ferritin levels in brain)

- Dopamine system dysfunction

- Genetic polymorphisms related to limb movement pathways

Medical Causes

- Diabetes neuropathy

- Kidney disease

- Pregnancy (typically temporary)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

Treatment

Some treatments include:

Non-pharmacological

- Leg massages

- Warm or cold compresses

- Regular exercise but not close to bedtime

- Avoid caffeine, nicotine, alcohol

Pharmacological

- Dopamine agonists (pramipexole, ropinirole)

- Iron supplementation

- Gabapentin for severe cases

General Etiology of Parasomnias

1. Biological Mechanisms

- Sleep stage instability leads to incomplete awakenings

- Overlap between wake and sleep states

- Genetic predisposition to arousal disorders

- Neurotransmitter imbalances: GABA, dopamine, norepinephrine

- Brainstem dysfunction in REM disorders

- Autonomic hyperreactivity

2. Psychological Factors

- Stress and anxiety elevate autonomic arousal

- Trauma increases REM intensity

- Maladaptive coping mechanisms worsen sleep fragmentation

3. Environmental Factors

- Sleep deprivation increases slow-wave sleep pressure

- Irregular sleep schedules

- Substance use can worsen parasomnias

- Noises or temperature variations can trigger partial awakenings

General Treatment Principles

Some general treatment principles include:

- Sleep Hygiene

- Maintain consistent sleep-wake schedule

- Avoid late naps

- Reduce screen exposure before bed

- Optimize bedroom environment

2. Psychotherapy

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for nightmares, anxiety, PTSD

- Relaxation training

- Trauma processing

3. Medication Management

- Benzodiazepines for NREM disorders

- Melatonin for RBD

- Dopamine agonists for RLS

- Prazosin for trauma-related nightmares

4. Safety Interventions

- Reinforcing doors/windows

- Removing weapons

- Padded bedroom

- Lower bed height

- Monitoring for dangerous behaviors

Conclusion

Parasomnias represent a breakdown in normal sleep regulation, where physiological systems activate at inappropriate times. They can be benign or severe, frightening or dangerous, and may signal underlying medical issues such as neurological disease or psychiatric stress.

Understanding these disorders through the lens of DSM-5, neuroscience, clinical psychology, and sleep medicine — as presented in the works of Butcher, Carson, Sarason, Nevid, and the APA — allows for comprehensive assessment and effective, targeted treatments. Early intervention ensures safety, reduces distress, and improves overall sleep quality.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Alloy, L. B., Riskind, J. H., & Manos, M. J. (2005). Abnormal Psychology: Current Perspectives (9th ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill.

Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (2005). Abnormal Psychology (4th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2014). Abnormal Psychology (15th ed.). Pearson.

Carson, R. C., Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (13th ed.). Pearson.

Nevid, J. S., Rathus, S. A., & Greene, B. (2014). Abnormal Psychology (9th ed.). Pearson.

Puri, B. K., Laking, P. J., & Treasaden, I. H. (1996). Textbook of Psychiatry. Churchill Livingstone.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, R. B. (2002). Abnormal Psychology: The Problem of Maladaptive Behavior (10th ed.). Pearson Education.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 3). 6 Important Parasomnias: DSM Classification, Etiology & Treatments. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/parasomnias/