Introduction

Group dynamics explores the influence of group settings on individual behavior, performance, decision-making, and interpersonal processes. In social psychology, group dynamics are vital to understanding real-world phenomena ranging from boardroom decisions to classroom participation and team-based activities.

Key constructs such as social facilitation, social loafing, and groupthink offer deep insights into how and why group membership affects individual actions. These constructs have been extensively researched and provide practical implications in various sectors including education, workplace management, sports, and policy formulation.

Read More- Social Psychology

1. Social Facilitation

Historical Foundations

The earliest observation of social facilitation dates back to Triplett (1898), who noticed that cyclists raced faster when competing with others than when cycling alone. This phenomenon spurred interest in the impact of others’ presence on individual performance. Zajonc (1965) further developed this concept with his Drive Theory, suggesting that the presence of others heightens arousal, which in turn enhances the performance of dominant (well-learned) tasks but impairs performance on non-dominant (new or complex) tasks.

Theoretical Perspectives

Zajonc’s Drive Theory posits that the presence of others induces arousal, leading to an increased likelihood of emitting the dominant response. If the task is simple or well-practiced, this response is likely to be correct, thereby improving performance. Conversely, in complex or unfamiliar tasks, the dominant response may be incorrect, leading to performance impairment (Zajonc, 1965).

The Evaluation Apprehension Theory (Cottrell, 1972) argues that performance changes are not merely due to the presence of others, but specifically due to concern about being evaluated. When individuals believe they are being judged, their arousal and effort increase.

Social Facilitation

Another explanation, the Distraction–Conflict Theory (Baron et al., 2017), suggests that the presence of others divides attention between the task and the audience, creating conflict that intensifies arousal and affects performance.

Empirical Evidence

Numerous studies support social facilitation. In Huguet et al. (1999), participants performing Stroop tasks did worse under observation due to cognitive overload. Conversely, Meumann (1904) found enhanced physical performance (e.g., weightlifting) in front of spectators. Bond and Titus (1983) conducted a meta-analysis of 241 studies, confirming that the presence of others generally improves performance on simple tasks and impairs it on complex ones.

Practical Applications

In sports, social facilitation explains the “home advantage” phenomenon where athletes often perform better with a supportive audience. In education, public speaking skills and test performance are affected by classroom dynamics. Teachers and trainers must consider task complexity and the presence of evaluative audiences when designing activities to maximize productivity.

2. Social Loafing

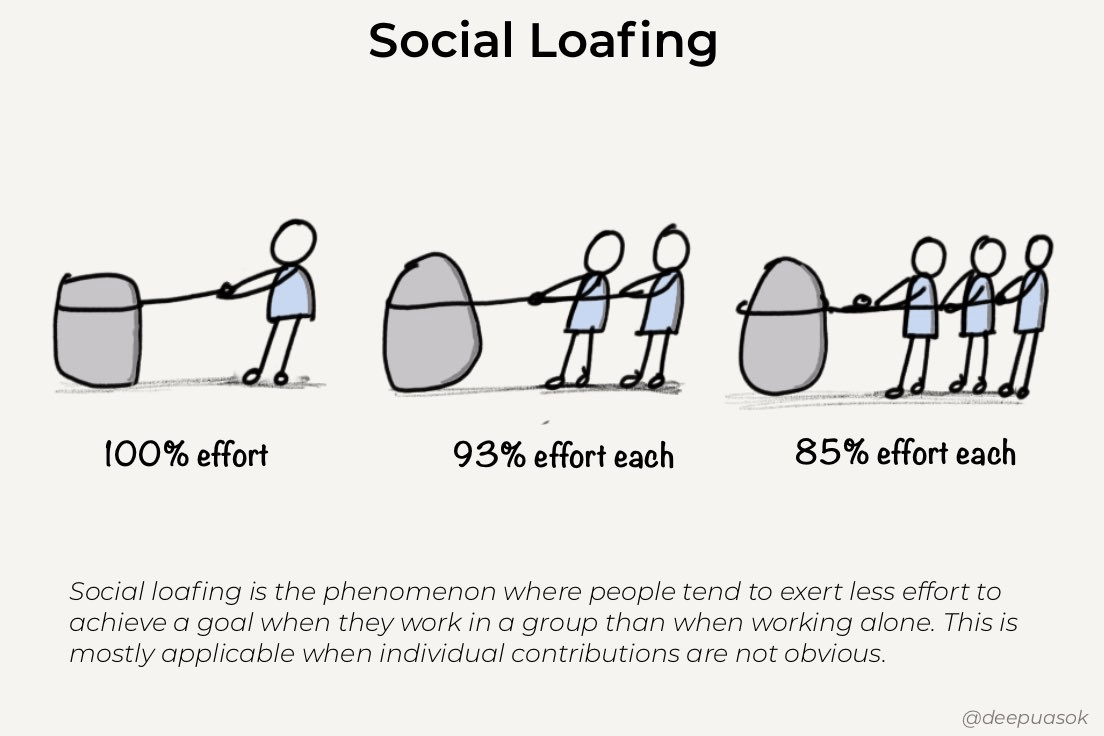

Social loafing refers to the tendency of individuals to put in less effort when working in groups compared to when working alone. The phenomenon was first documented by Ringelmann (1913), who observed that individuals exerted less effort in a group rope-pulling task. Later research by Ingham et al. (1974) eliminated coordination loss as a factor, highlighting motivational losses as the primary cause.

Social Loafing

Theoretical Frameworks

- Diffusion of Responsibility is a central theory explaining social loafing. As group size increases, individuals perceive their effort as less crucial, reducing motivation (Latané et al., 1979).

- Equity Theory suggests that when individuals perceive inequity in the distribution of workload or rewards, they reduce their effort to match perceived input-output ratios.

- The Free-Rider Effect occurs when individuals believe others will compensate for their lack of effort, thus justifying disengagement.

Research Evidence

Karau and Williams (1993) conducted a meta-analysis of 78 studies and found strong support for the link between group size, individual identifiability, and effort levels. Harkins and Szymanski (1989) found that making individual performance identifiable reduces loafing significantly. Social loafing is less likely when tasks are meaningful, contributions are visible, and the group is cohesive.

Practical Implications

In workplaces, social loafing can reduce team productivity. Solutions include role clarity, performance tracking, and individualized rewards. In education, group assignments often suffer unless individual contributions are assessed separately. Effective strategies include using peer evaluations, assigning distinct roles, and fostering accountability.

3. Groupthink

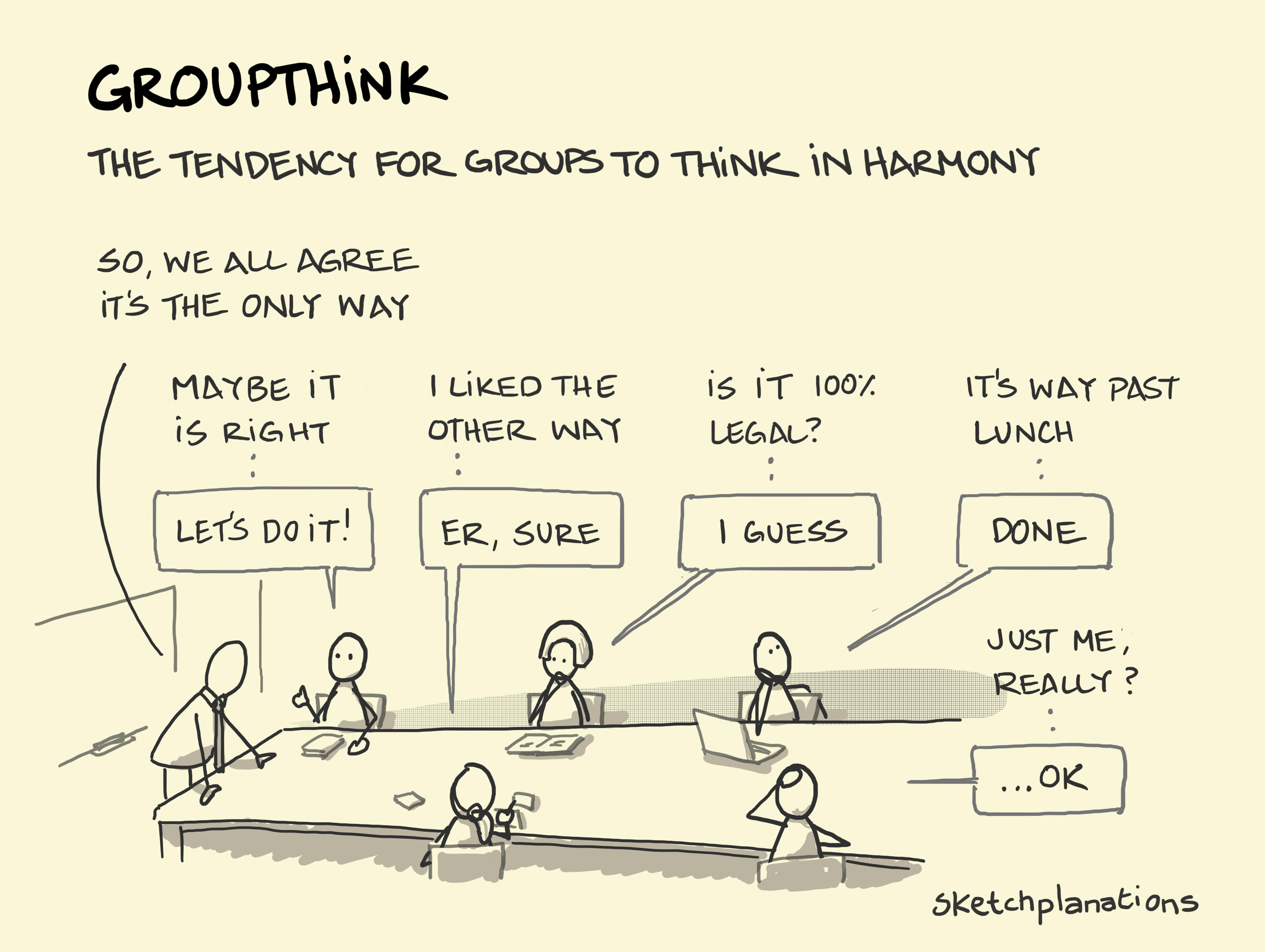

Coined by Janis (1972), groupthink refers to the deterioration of mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment in highly cohesive groups striving for consensus. Symptoms include:

- Illusion of invulnerability

- Rationalization

- Stereotyping of outsiders

- Self-censorship

- Illusion of unanimity

- Direct pressure on dissenters

- Mindguards

- Unquestioned belief in group morality

Groupthink

Antecedents

Groupthink arises when groups exhibit high cohesiveness, isolation from outside opinions, directive leadership, homogeneity of members, and stress from external threats. These conditions suppress dissent and discourage critical thinking (Janis, 1972).

Real-World Case Studies

- Bay of Pigs Invasion: U.S. policymakers ignored dissenting opinions, leading to a failed military operation.

- Challenger Disaster: NASA officials overlooked engineers’ warnings under pressure for consensus.

- Swissair Collapse: Overconfidence and boardroom homogeneity contributed to financial mismanagement (Turner & Pratkanis, 2002).

Preventive Measures

Strategies to avoid groupthink include:

- Encouraging open dialogue and dissent

- Assigning a devil’s advocate

- Inviting external expert critiques

- Subdividing the group for independent discussions

- Leaders withholding their opinions during early deliberations

Shared Mechanisms

Social facilitation and social loafing both revolve around the presence of others and how it affects arousal, motivation, and accountability. Groupthink, while different in form, shares psychological processes such as conformity pressure and diffusion of responsibility. Group cohesion plays a paradoxical role: it can enhance morale and cooperation but also stifle critical thought and individual accountability.

Contextual Moderators

- Task complexity and audience evaluation modulate social facilitation.

- Group size, task significance, and individual visibility affect social loafing.

- Leadership style, group diversity, and decision-making protocols influence groupthink susceptibility.

Conclusion

Understanding group dynamics is essential for improving performance, collaboration, and decision-making in various group settings. While social facilitation can enhance performance under the right conditions, social loafing and groupthink highlight the pitfalls of collective work without accountability or critical reflection. By applying theory-driven strategies to manage these dynamics, educators, managers, and policymakers can foster healthier, more effective group environments.

References

Baron, R. A., & Branscombe, N. R. (2017). Social psychology (14th ed.).

Pearson. Bond, C. F., & Titus, L. J. (1983). Social facilitation: A meta-analysis of 241 studies. Psychological Bulletin, 94(2), 265–279.

Cottrell, N. B. (1972). Social facilitation. In C. G. McClintock (Ed.), Experimental social psychology (pp. 185–236).

Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Diehl, M., & Stroebe, W. (1987). Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: Toward the solution of a riddle. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 497–509.

Harkins, S. G., & Szymanski, K. (1989). Social loafing and group evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(6), 934–941.

Huguet, P., Galvaing, M.-P., Monteil, J.-M., & Dumas, F. (1999). Social presence effects in the Stroop task: Further evidence for an attentional view of social facilitation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(5), 1011–1024.

Ingham, A. G., Levinger, G., Graves, J., & Peckham, V. (1974). The Ringelmann effect: Studies of group size and group performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10(4), 371–384.

Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink: A psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes.

Houghton Mifflin. Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 681–706.

Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(6), 822–832.

Meumann, E. (1904). Über den Einfluss der Übung auf die geistige Leistungsfähigkeit. Leipzig.

Ringelmann, M. (1913). Recherches sur les moteurs animés: Travail de l’homme. Annales de l’Institut National Agronomique, 12, 1–40.

Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. American Journal of Psychology, 9, 507–533.

Turner, M. E., & Pratkanis, A. R. (2002). Groupthink. In R. K. Mullen & C. Cooper (Eds.), Theories of group behavior (pp. 215–239). Springer.

Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149(3681), 269–274.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, July 30). Group Dynamics and 3 Important Theories of It. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/group-dynamics-and-3-important-theories-of-it/