Contents

Introduction

Classical conditioning is one of the most basic forms of learning, yet it plays a critical role in shaping both human and animal behaviors. It involves learning through association and was first studied in detail by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov. His experiments with dogs laid the foundation for understanding how an organism can be conditioned to respond to a previously neutral stimulus.

Also called Pavlovian conditioning; respondent conditioning; Type I conditioning; Type S conditioning.

Definition of Learning

Learning can be broadly defined as ‘a relatively permanent change in behavior that occurs due to experience or practice.’ This definition emphasizes two key points: first, that learning results in a change in behavior; and second, that this change is not fleeting but relatively permanent. Learning is a fundamental aspect of human and animal life, enabling organisms to adapt to their environments, solve problems, and avoid harm.

Not all changes in behavior are due to learning. Some changes are a result of biological maturation or physical development, such as growing taller or increasing in strength. Reflexes, which are unlearned, involuntary responses, are another example of behaviors not acquired through learning. For instance, the knee-jerk reaction when a doctor taps your patellar tendon is an automatic, biological response rather than a learned one.

Read More- What is Learning?

Ivan Pavlov’s Contribution to Learning Theory

Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) was a Russian physiologist best known for his groundbreaking work in the field of behavioral psychology, specifically for his discovery of classical conditioning. Born in Ryazan, Russia, Pavlov initially studied theology but soon shifted his focus to the natural sciences. He pursued a medical degree and specialized in physiology, becoming particularly interested in the physiology of digestion. In 1904, Pavlov was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his research on the digestive system, particularly his work on the functions of the pancreas.

Pavlov’s most famous research, however, involved the study of conditioned reflexes. While investigating the digestive system of dogs, Pavlov noticed that they began to salivate not only when food was presented but also when they heard the footsteps of the lab assistant bringing the food. Intrigued, Pavlov set out to explore this phenomenon. He conducted experiments in which he paired the presentation of food (an unconditioned stimulus that naturally causes salivation) with a neutral stimulus, such as the sound of a bell. After repeated pairings, the dogs began to salivate in response to the bell alone, even when no food was presented.

This discovery led Pavlov to develop the theory of classical conditioning, which explained how certain stimuli could trigger automatic responses through learned associations. His work profoundly influenced psychology, particularly the behaviorist school of thought, which emphasized observable behaviors over internal mental processes.

Pavlov’s background in physiology shaped his approach to studying behavior, as he viewed psychological phenomena as biological processes. His methodical, scientific approach to studying reflexes helped establish experimental psychology as a more empirical, measurable discipline. His work laid the foundation for later developments in learning theory, behaviorism, and modern psychology.

Elements of Classical Conditioning

Key Concepts in Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning consists of several key elements that form the backbone of this learning process-

- Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS)– The UCS is a stimulus that naturally and automatically triggers a response without any prior learning. In Pavlov’s experiment, the UCS was the food, which naturally caused the dogs to salivate.

- Unconditioned Response (UCR)– The UCR is the automatic, involuntary reaction to the UCS. In Pavlov’s case, the salivation that occurred when the dogs were presented with food was the UCR.

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS)– A previously neutral stimulus that, after being repeatedly paired with the UCS, becomes associated with it and elicits a learned response. In Pavlov’s experiment, the sound of the metronome became the CS after it was repeatedly paired with the UCS (food).

- Conditioned Response (CR)– The CR is the learned response to the conditioned stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiment, the dogs’ salivation in response to the sound of the metronome (even in the absence of food) was the CR.

Pavlov’s Dog Experiment

Ivan Pavlov discovered that dogs could be trained to associate a neutral stimulus, like the sound of a metronome, with food. Initially, the dogs naturally salivated when presented with food, an automatic response called the unconditioned response (UCR) to the unconditioned stimulus (UCS), which in this case was the food. The sound of the metronome was initially a neutral stimulus (NS) and caused no salivation. However, after repeatedly pairing the sound of the metronome with the presentation of food, the dogs began to salivate at the sound alone. The sound had become a conditioned stimulus (CS), and the salivation in response to the sound was now a conditioned response (CR).

Pavlov’s Experiment

Classical Conditioning can be understood in three phases-

- Before Conditioning- In this phase, the neutral stimulus (the sound of the metronome) does not trigger any salivation in the dogs. At this point, the food (UCS) naturally triggers the unconditioned response (UCR) of salivation, but the metronome does not elicit any response.

- During Conditioning- Pavlov repeatedly presented the metronome’s sound (neutral stimulus) just before giving the dogs food (UCS). Over several trials, the dogs began to associate the sound with the impending arrival of food. As a result, the dogs started to salivate (UCR) in response to the metronome.

- After Conditioning- After several pairings, the sound of the metronome alone (now the CS) was sufficient to elicit salivation (now the CR). The dogs had learned to associate the sound of the metronome with the presentation of food, demonstrating the process of classical conditioning.

Stimulus Generalisation

In classical conditioning, once an individual or animal has learned to associate a conditioned stimulus (CS) with an unconditioned stimulus (UCS), the learned response often spreads to similar stimuli in a phenomenon called stimulus generalization. This means that the conditioned response (CR) is triggered by stimuli that resemble the original CS, even if they were never paired with the UCS during the conditioning process.

For example- if someone has developed a conditioned anxiety response to the sound of a dentist’s drill (CS) after associating it with pain (UCS), they may also feel anxious when they hear other high-pitched, mechanical sounds, such as a hairdryer, vacuum cleaner, or grinder. These stimuli are not exactly the same but are similar enough that the learned response generalizes to them.

Stimulus generalization is a useful adaptive feature, as it enables organisms to respond appropriately to a range of potentially dangerous or important stimuli without having to experience each one individually. For example, if a person were bitten by a large dog, it might be adaptive for them to also be cautious around similarly large dogs, or even other dogs in general, because the traits of the animal resemble those that caused harm.

Stimulus Discrimination

While stimulus generalization is common, organisms can also learn to differentiate between similar stimuli in a process known as stimulus discrimination. Through repeated experiences, an individual can learn that not all similar stimuli will produce the same outcomes, allowing them to respond only to the most relevant stimuli. In other words, stimulus discrimination helps refine learned behaviors, ensuring that organisms react appropriately to the specific conditions in their environment.

For example- if a person initially responds with anxiety to both the sound of a dentist’s drill and the sound of a hairdryer (due to their similarity), they may eventually learn to discriminate between the two sounds. Over time, with repeated exposure to the hairdryer without the negative consequences associated with the dentist’s drill, they can learn that the hairdryer sound does not lead to pain or discomfort. As a result, they will continue to feel anxious in response to the dentist’s drill but will no longer feel anxious when hearing the hairdryer. Stimulus discrimination, therefore, ensures that the individual only reacts when the most appropriate or dangerous stimulus is present.

Extinction

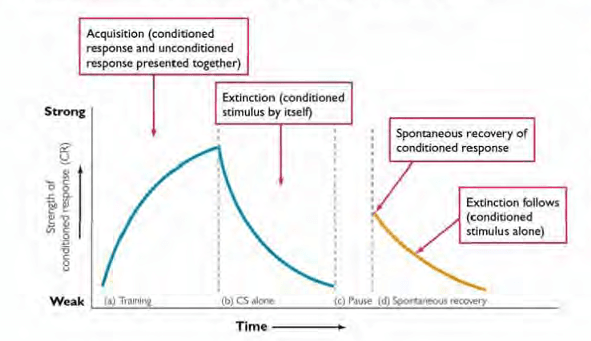

One of the key features of classical conditioning is that learned behaviors are not always permanent. The process of extinction occurs when the conditioned stimulus (CS) is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus (UCS), leading to a gradual weakening and eventual disappearance of the conditioned response (CR).

For example- in Pavlov’s original experiment, once the dogs had been conditioned to salivate at the sound of a metronome (CS) paired with food (UCS), extinction would occur if Pavlov repeatedly rang the metronome without presenting food afterward. Over time, the dogs would stop salivating when they heard the metronome because the learned association between the sound and the food had been broken. Extinction is an important aspect of classical conditioning because it shows that learned behaviors can be unlearned when the conditions change.

Spontaneous Recovery

Even after extinction has occurred, classical conditioning shows that the learned behavior can reappear suddenly, a phenomenon known as spontaneous recovery. This occurs when, after a period of time, the conditioned stimulus (CS) is presented again, and the conditioned response (CR) returns, albeit usually in a weaker form.

In Pavlov’s experiment, for example, after the dogs’ salivation response to the metronome had been extinguished, Pavlov could wait for some time and then ring the metronome again. The dogs would often begin to salivate again, even though no food was presented, demonstrating spontaneous recovery. The response, however, would typically be weaker than before, and if the food still did not follow the metronome sound, the response would quickly extinguish again.

Acquisition, Extinction, and Spontaneous Recovery

Higher-Order Conditioning

Higher-order conditioning is an advanced form of classical conditioning where a conditioned stimulus (CS) that has already been established through previous conditioning is paired with a new neutral stimulus (NS). Over time, this new neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus in its own right, capable of eliciting the conditioned response (CR) even in the absence of the original unconditioned stimulus (UCS). Essentially, the process creates a chain of associations where a previously neutral stimulus is conditioned not directly by the unconditioned stimulus but by an already established conditioned stimulus.

In basic classical conditioning, a neutral stimulus is repeatedly paired with an unconditioned stimulus to elicit an unconditioned response (UCR). Over time, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus, and the response elicited by it becomes a conditioned response. Higher-order conditioning builds upon this by introducing an additional neutral stimulus, which is associated with the already conditioned stimulus, without the presence of the unconditioned stimulus.

Example of Higher-Order Conditioning

In the original experiment, Pavlov conditioned his dogs to salivate at the sound of a metronome by pairing the sound with the presentation of food. The sound of the metronome (CS) elicited a conditioned response (salivation) because the dogs had learned to associate it with food (UCS).

In higher-order conditioning, Pavlov could introduce a new neutral stimulus—such as a flashing light—and pair it with the sound of the metronome (CS). The light would initially have no effect on the dogs, as it is a neutral stimulus. However, through repeated pairing of the light (NS) with the metronome (CS), the dogs would begin to associate the light with the metronome, and consequently, with salivation. Eventually, the flashing light alone would trigger the salivation response, even without the sound of the metronome or the presentation of food.

In this example-

- First-order conditioning– The metronome (CS) was paired with food (UCS), leading to salivation (CR).

- Higher-order conditioning– The light (new NS) was paired with the metronome (CS), eventually leading to salivation (CR) in response to the light alone.

Classical Conditioning and Personality

Classical conditioning, introduced by Ivan Pavlov, is a learning process where an individual forms associations between stimuli and responses. This concept, though simple, plays a significant role in shaping personality. Personality, which is the combination of consistent thoughts, behaviors, and emotions that define a person, is influenced not only by genetic factors but also by learned experiences. Classical conditioning affects emotional responses, behavior patterns, and interpersonal interactions, all of which contribute to the development of personality traits.

Emotional Response

Classical conditioning influences personality by shaping emotional responses. For instance, if a child repeatedly experiences fear in response to a particular stimulus (such as being scolded in public), they may develop anxiety in similar situations. This learned response becomes a part of their personality, leading to traits like shyness or social anxiety. Conversely, positive associations, such as being praised for social interactions, may foster confidence and extroversion.

Habit

Habits are another way classical conditioning impacts personality. For example, if a child is rewarded for diligent work (UCS), they may develop a habit of persistence and discipline (CR). Over time, these learned behaviors become automatic and form key parts of their personality.

In conclusion, classical conditioning helps mold personality by creating enduring emotional responses and habitual behaviors. Through repeated experiences, individuals learn to react to the world in ways that shape their enduring personality traits.

Evidence Supporting Classical Conditioning

Numerous experimental studies have provided strong evidence for the principles of classical conditioning.

One of the most famous studies in human conditioning was conducted by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner in 1920. Known as the Little Albert Experiment, this study involved conditioning an infant (Albert) to fear a white rat by pairing the presence of the rat with a loud, frightening noise (UCS). After several pairings, Albert began to exhibit fear (CR) when presented with the rat (CS) alone. This study not only demonstrated the power of classical conditioning in humans but also illustrated how stimulus generalization could occur, as Albert’s fear extended to other similar objects, such as a white rabbit or a fur coat.

Other studies have explored classical conditioning in various contexts. For example, taste aversion is a well-documented form of classical conditioning that occurs when an individual associates a particular taste (CS) with nausea or illness (UCS). This phenomenon has been studied extensively in both humans and animals and illustrates how classical conditioning can shape food preferences and aversions.

Conclusion

Classical conditioning is one of the most fundamental and well-understood forms of learning, and it has far-reaching implications for both human and animal behavior. By understanding how organisms learn to associate stimuli with specific responses, we gain insight into how behaviors are acquired, modified, and sometimes extinguished. Pavlov’s pioneering research laid the groundwork for a vast body of knowledge that continues to influence psychology, education, and even therapeutic practices today.

Through classical conditioning, we learn to avoid painful or harmful experiences, such as touching a hot stove or encountering dangerous animals, and we also develop positive associations that guide our behavior in more beneficial directions. From advertising strategies to therapeutic interventions, classical conditioning remains a powerful tool for understanding and shaping behavior.

References

Ciccarelli, S. K., & White, J. N. (2012). Psychology: An Exploration (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Learning Solutions.

Pavlov, I. P. (1926). Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex. Oxford University Press.

Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Lectures on Conditioned Reflexes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rescorla, R. A. (1988). Pavlovian Conditioning: It’s Not What You Think It Is. American Psychologist, 43(3), 151-160.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned Emotional Reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(1), 1-14.

Feldman, R. S. (2017). Understanding Psychology (13th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.