Introduction

As individuals progress into later stages of life, they face unique stressors such as health decline, bereavement, financial insecurity, and changes in social roles. Coping mechanisms become crucial for older adults as they navigate these challenges and strive to maintain psychological well-being and quality of life.

Coping can be understood as the cognitive and behavioral strategies that individuals use to manage stress and adapt to difficult circumstances (Taylor, 1999). In older adulthood, coping takes diverse forms, ranging from problem-solving approaches to spiritual practices, and is often supported by external resources such as family, friends, and community networks.

Read More: Geropsychology

Religious and Spiritual Coping in Aging

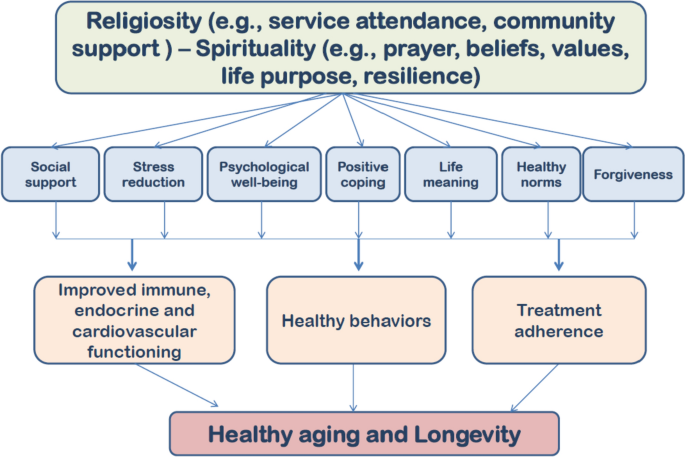

Religion and spirituality serve as vital coping resources for many older adults, offering both psychological comfort and social integration. Johnson and Walker (2016) argue that spiritual beliefs provide meaning and continuity in life, helping older individuals face loss, illness, and the inevitability of death. Practices such as prayer, meditation, participation in religious communities, and ritual observances contribute to resilience by reducing feelings of isolation and hopelessness.

Spirituality and Longevity

Birren and Schaie (2001) emphasize that religious coping is particularly significant for elderly populations due to its dual function as both a personal and communal resource. Religion helps individuals reframe adversity, interpreting stressors as part of a divine plan or an opportunity for spiritual growth. Schulz (2006) also highlights the positive health outcomes linked to religious coping, including lower rates of depression, improved immune functioning, and enhanced emotional stability. Spirituality provides not only solace but also a cognitive framework to reconcile with existential concerns.

Types of Coping in Aging

Coping strategies among older adults vary depending on the nature of the stressor, individual personality traits, cultural background, and available resources. These strategies can be broadly classified into problem-focused, emotion-focused, meaning-focused, and avoidance coping.

- Problem-Focused Coping: Problem-focused coping involves directly addressing the source of stress. For example, managing chronic illnesses by adhering to treatment regimens, modifying diets, or engaging in physical exercise represents problem-focused coping. Feldman and Babu (2011) observe that this coping style is effective when stressors are perceived as controllable. Older adults who remain proactive in managing their health or finances often demonstrate greater psychological resilience and autonomy.

- Emotion-Focused Coping: Emotion-focused coping emphasizes the regulation of emotional responses rather than altering the stressor itself. This form of coping is particularly relevant when stressors are beyond an individual’s control, such as bereavement or irreversible health decline. Strategies include seeking emotional support, engaging in relaxation techniques, practicing mindfulness, or pursuing creative hobbies. Comer (2007) notes that emotion-focused coping can alleviate distress and prevent the buildup of negative emotions, contributing to improved mental health outcomes.

- Meaning-Focused Coping: Meaning-focused coping involves reinterpreting stressful situations in ways that highlight personal growth, wisdom, or resilience. Hurlock (1981) explains that older adults often draw upon life experiences to find meaning in adversity, reframing loss or illness as part of the human journey. This approach supports optimism and fosters acceptance, helping older adults maintain psychological equilibrium in the face of significant challenges.

- Avoidance Coping: Avoidance coping entails denying, minimizing, or ignoring stressors. While it can provide temporary relief, long-term reliance on avoidance may exacerbate distress (Taylor, 1999). Older adults might use avoidance strategies when overwhelmed by uncontrollable stressors, such as terminal illness. Although maladaptive in many cases, short-term avoidance can serve as a buffer, allowing time to gradually process painful realities.

External Resources for Coping

Some external resources for coping include:

- Social Support: Social support is one of the most significant external coping resources for older adults. Feldman and Babu (2011) underscore that strong social networks buffer against stress, reduce feelings of loneliness, and enhance overall life satisfaction. Emotional support from friends and peers, informational support from professionals, and practical support such as help with daily tasks all contribute to effective coping. Regular social interaction has been linked to reduced cognitive decline and better emotional health.

- Family Support: Family remains a central pillar of coping in aging. Hurlock (1981) notes that supportive family relationships foster a sense of belonging and reduce anxiety during periods of illness or transition. Children and grandchildren often provide both instrumental and emotional support, helping older adults maintain dignity and independence. In collectivist cultures, family caregiving is not only a duty but also a source of comfort for aging individuals (Eyetsemitan & Gire, 2003).

- Community and Institutional Resources: Community programs, religious organizations, and senior centers play vital roles in enhancing coping. Johnson and Walker (2016) emphasize the importance of spiritual communities in sustaining hope and belonging. Meanwhile, healthcare institutions provide essential support through counseling, therapy, and medical care. Schulz (2006) points out that such resources are especially crucial for individuals without strong family networks.

The Interplay of Internal and External Coping Resources

Coping in aging is not limited to internal strategies but is strengthened by the interplay with external resources. For instance, religious coping often operates in tandem with social support from religious communities. Similarly, problem-focused coping may require institutional resources such as healthcare access. Taylor (1999) highlights that the effectiveness of coping strategies depends on both individual agency and the broader environment in which an individual is embedded.

Coping and Aging

Cultural Perspectives on Coping in Aging

Coping styles are deeply influenced by cultural values and traditions. Eyetsemitan and Gire (2003) argue that in developing countries, reliance on family and community networks is a primary coping mechanism due to limited institutional support. Religious and spiritual coping also tends to be more prominent in such contexts, where faith plays a central role in daily life. In contrast, older adults in developed countries may rely more on formal support systems, such as counseling services and assisted living institutions. Nonetheless, across cultures, social connectedness remains a critical factor in successful coping.

Coping and Active Aging

Challenges to Effective Coping

While coping strategies provide resilience, several barriers can hinder effective coping in aging. Declining health can limit participation in social or spiritual activities. Financial strain may restrict access to healthcare or community programs. Moreover, ageism and societal neglect may deprive older adults of meaningful social roles, further complicating coping efforts. Comer (2007) observes that individuals with limited support networks are especially vulnerable to maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as avoidance or withdrawal.

Conclusion

Coping in aging is a dynamic and multifaceted process shaped by personal, spiritual, and social resources. Religious and spiritual coping provides existential meaning and resilience, while problem-focused, emotion-focused, and meaning-focused strategies allow individuals to manage diverse stressors.

External resources such as social support, family involvement, and community networks further strengthen the coping process. However, cultural contexts, health challenges, and economic conditions influence how coping unfolds in later life.

Recognizing and supporting effective coping strategies is essential for promoting healthy and fulfilling aging. By fostering strong support systems and encouraging adaptive coping mechanisms, societies can help older adults maintain dignity, resilience, and psychological well-being in the face of life’s inevitable challenges.

References

Birren, J. E., & Schaie, K. W. (2001). Handbook of the Psychology of Aging (5th Ed.). Academic Press: London.

Comer, R. J. (2007). Abnormal Psychology (6th Ed.). Worth Publishers.

Elizabeth, B. Hurlock. (1981). Developmental Psychology: A Life-Span Approach (5th Ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill: Delhi.

Eyetsemitan, F. E., & Gire, J. T. (2003). Aging and Adult Development in the Developing World: Applying Western Theories and Concepts. Library of Congress.

Feldman, R. S., & Babu, N. (2011). Discovering the Life Span. Pearson.

Johnson, M., & Walker, J. (2016). Spiritual Dimensions of Aging. Cambridge University Press: UK.

Schulz, R. (2006). The Encyclopaedia of Aging: A Comprehensive Resource in Gerontology and Geriatrics (4th Ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

Taylor, S. E. (1999). Health Psychology (4th Ed.). McGraw-Hill International (Ed.) Psychology Series.

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, September 3). Coping & Aging: Religious-Spiritual Coping, 4 Important Types of Coping, and External Resources. Careershodh. https://www.careershodh.com/coping-aging/